The exact date which Thomas Wisedell began working for R. J. Withers is unknown, though he was working there at least by 1865, however, 1862 or 63 is quite probable. By that time, Withers was already a well-respected architect who specialized in restoring and rebuilding Saxon, Norman and gothic churches throughout England and Wales. Before getting into the specific works by Withers in the 1860’s, a brief introduction should be given.

Withers was born in Shepton Mallet in 1824 and was home-schooled until 1834 when he was sent off to a boarding school in Newport on the Isle of Wight. In 1836, he briefly attended school in Horsington, Somerset but returned to Newport to finish his studies. Following his formal education, Withers was articled to Thomas Hellyer (1811-94) of Ryde on the Isle of Wight between 1839 and 1844. Where Hellyer received his training is unknown, though he was an architect and surveyor who had fallen under the influence of the writings of A. W. N. Pugin, becoming an active member of the Ecclesiastical Society and the development of the Gothic Revival movement. Having just opened his independent practice in 1839, Withers was one of his earliest (if not his first) draftsman.

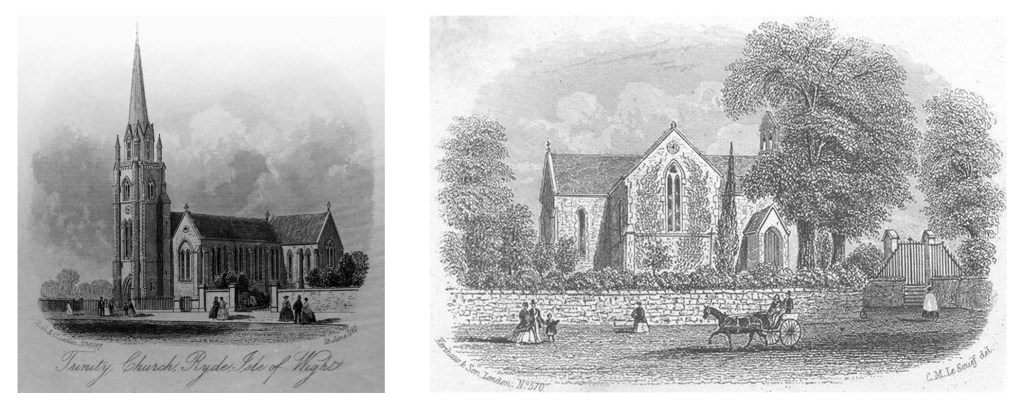

During Withers’ apprenticeship, Hellyer’s office produced designs for at least two houses as well as the expansion of the pier-head at Ryde (with James Langdon, builder). However, the projects which seem to have paved the way for Withers future career were the Church of the Holy Trinity (1840-46) in Ryde, the Church of St John (1841-43) in Oakfield, a suburb south of Ryde, and the restoration and rebuilding of the twelfth century Church of the Holy Cross at Binstead, just west of Ryde on the Isle of Wight (1843-1844).

Though Heller was fond of Pugin, Holy Trinity and St. John’s both were designed in an early English, lanceted style reflecting the Ecclesiastical Society’s preference for late 12th and early 13th century churches as an appropriate model for contemporary Britain.

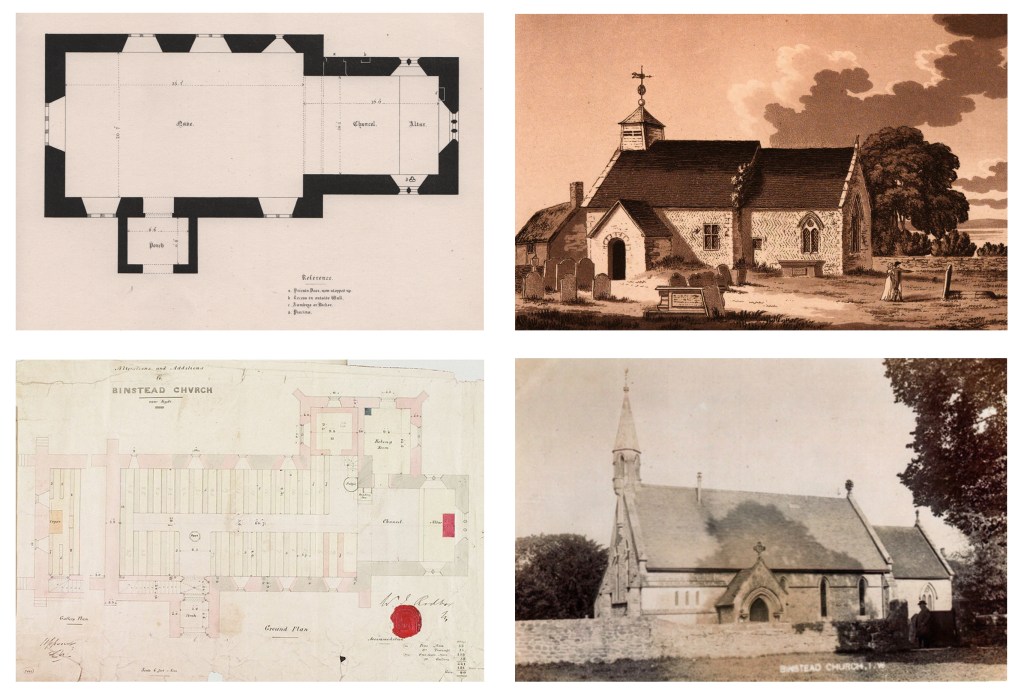

Perhaps even more than Holy Trinity or St. John’s, Heller’s enlargement and restoration the twelfth century Church of the Holy Cross at Binstead, just west of Ryde was arguably the most important project for helping Robert Withers establish his early practice. The church is thought to have been built around 1150 c.e. by masons working at the nearby stone quarry, incorporating herringbone masonry and what was thought to be various Saxon era carvings. It is now believed that that the carvings actually date to the Norman period but were carved in an older, Saxon style.

Top Right: Engraving on Holy Cross, Binstead. From Charles Tompkins, A Tour of the Isle of Wight (1796).

Bottom Left: Hellyer’s plan dated 1844. https://images.lambethpalacelibrary.org.uk/luna/servlet/detail/LPLIBLPL~34~34~80914~113221.

Bottom Right: Photo ca. 1906 of Holy Cross, Binstead. Collection of Author.

By 1843 the church had fallen into what was described as “an almost inconceivably wretched state.” Apparently there were problems with the roof, some of the seating had been moved into the chancel and the pulpit and lectern had been placed on either side of the alter. Hellyer’s task was to restore the chancel while dismantling the rest of the church and erect a new the porch and larger nave with new fittings to accommodate more parishioners. Before most of the church was dismantled, Withers had made measures drawings of the original plan, though drawings of details such as carvings found in keystone blocks and window tracery seem to have been made after those features had been removed.

The drawings made by Withers had been sent to the Cambridge Camden Society (later the Ecclesiastical Society). Apparently, as early as 1842, Withers had been sending drawings of twelfth, thirteenth and fourteenth century architectural details to the Society. In acknowledgement of those contributions and having completed his architectural training, Withers was elected as a member of the Cambridge Camden Society on the fifth of March, 1844. And with that, his apprenticeship under Thomas Heller was completed and Withers soon on a tour of churches and abbeys around England and parts of the European continent.

When Withers returned to England in 1845, he settled in Lancaster and spent a year working with architect and historian Edmund Sharpe (1809-1877) as a draftsman, primarily assisting in publications on Gothic architecture. Most notably, Withers helped create images for Sharpe’s Architectural Parallels, a twelve-part series documenting details of 12th and 13th century English Gothic abbeys and published between 1845 and 1848 (with a supplement also published in 1848 which primary relied on Withers drawings). Withers also drew illustrations for Sharpe’s two-volume set on late 12th and 13th century decorated window tracery published in 1849.

It was perhaps through Sharpe that Withers published two articles in 1845 in volume four of John Weale’s Quarterly Papers on Architecture; one showing the stone carvings and window details of the Church of the Holy Cross at Binstead, and the other documenting thirteenth century encaustic tiles at St. Marie’s Abbey at Beaulieu, England.

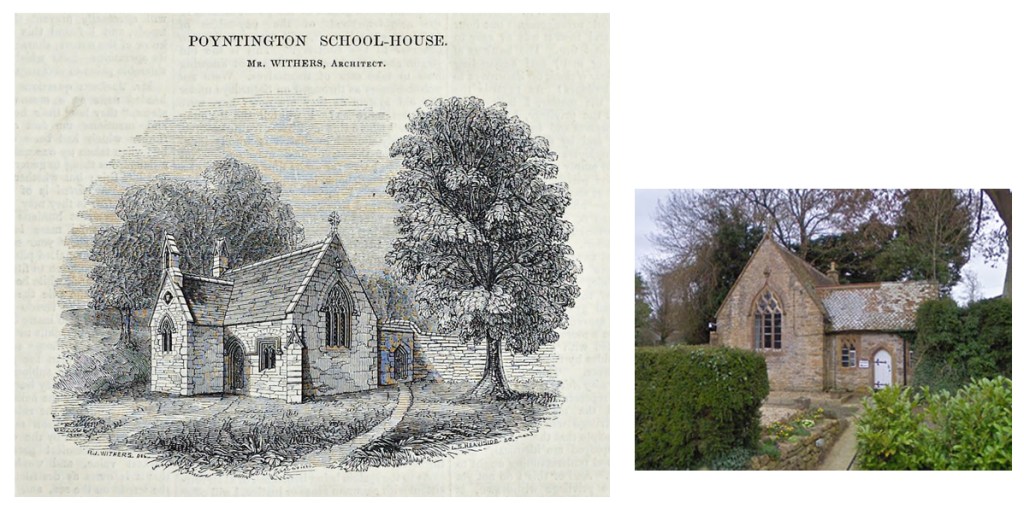

In 1846, Withers moved to Sherbourne, Dorset, where his parents and younger brother had moved in 1839. Withers soon gained commissions to restore and rebuild nearby parish churches in the Dorset villages of Hilfield, Poyntington, Lillington and Trent and it was in Poyntington that he was asked to design a schoolhouse; perhaps the first building that was completely of his own design.

Right: Image from Google Maps.

By May of 1849, Withers had enough experience that he was elected as an associate member of the Institute of British Architects at their annual meeting. That same year, he was awarded commissions to restore and rebuild the fifteenth century churches of St. Andrew at Leigh and St Mary’s at Melbury-Bubb, both in Dorset County. For both projects, the funding was delayed and would be completed five years later by R.H. Shout of Yeovil. Apparently, Withers had gotten frustrated with the delays and was also not happy living in Sherbourne, so he decided to move to London.

What may have spurred this decision was that his younger brother, Frederick Clarke Withers (1828-1901) had also become an architect and had completed his apprenticeship to architect Edward Mondey in Dorchester. The brothers moved to London in either late 1849 or early 1850 and both were employed in the office of Thomas Henry Wyatt (1807-1880) under whom they also worked for the London Improvement Commission. At that time, Wyatt was designing at least five churches, a hospital and an asylum.

The brothers move to London coincided with the the rise of the Pre-Rafaelites, the writings of John Ruskin and the designs of Owen Jones as well as the 1851 opening of the Chrystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park. In February of 1852, Frederick left London to work for Calvert Vaux and Andrew Jackson Downing in Newburgh, New York and in 1854, Withers would marry Catherine Vaux (sister of Calvert Vaux).

Also in 1854, R. J. Withers begin working for T.H. Wyatt’s younger brother, Matthew Digby Wyatt (1820-1877) who charged with rebuilding the Chrystal Palace at Sydenham. Withers was hired to create drawings to be displayed in the Medieval Court which had been designed by Wyatt. This project placed Withes among the best designers and craftsmen in London, and within a few years, he would be seen as one of their peers.

The following year, Withers re-established his private practice and just as his career had begun he was again called on to restore and enlarge gothic churches. By this time, however, his reputation had grown considerably and rather than being tied to Dorset, he was now working all throughout England and Wales.

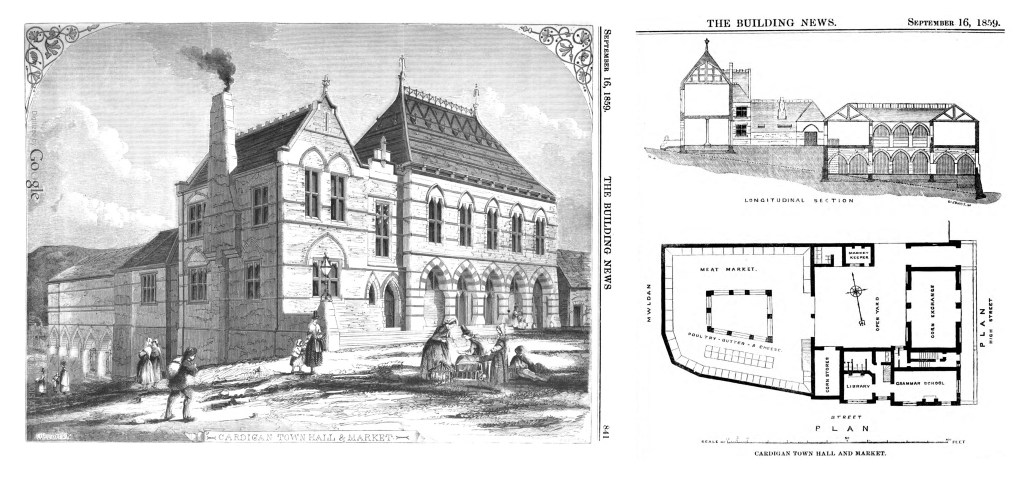

Perhaps Withers’ first non-ecclesiastical commission of note would be located in the ancient Welsh city of Cardigan. Between 1856 and 1863, Withers would design at least five projects there, the most important being a complex of municipal buildings which included a guildhall, corn exchange, market, library and grammar school; all designed in 1856 and completed in 1860.

With this project, Withers exhibited a decisive turn towards polychromy espoused by John Ruskin. Withers seems to have also relied heavily on examples found in George Edmund Street’s Brick and Marble in the Middle Ages which been published in 1855 and quite influential in demonstrating how Ruskin’s principles could actually be applied by architects.

Like many architects and builders throughout Britain, Withers would take a cue from William Butterfield’s All Saints Church in London which had been designed in 1849 and constructed between 1850 and 1859. In April of 1850, Parliament repealed the tax on bricks, freeing architects to explore modern church design without the reliance on stone that was preferred by the Ecclesiastical Society. By the mid-late 1850’s, enough architects were designing in brick, that even the Ecclesiastical Society had evolved a more liberal stance towards church design.

Right: https://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/LIN/LittleCawthorpe

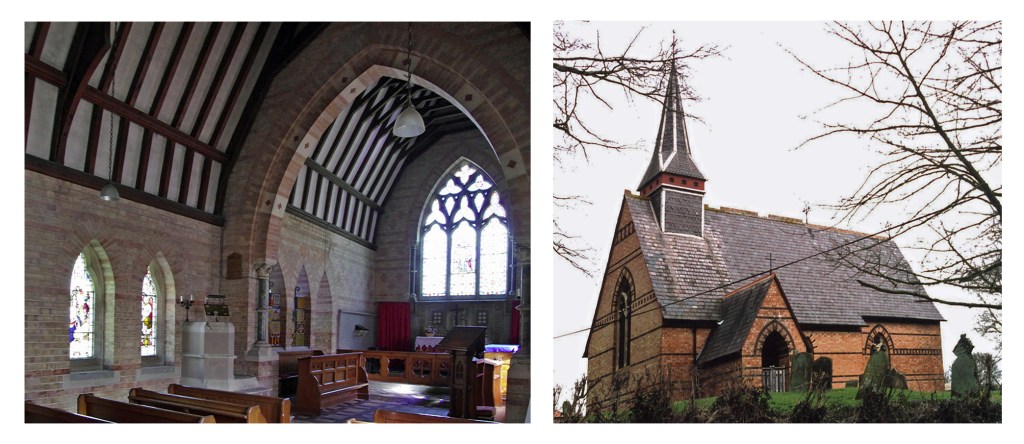

In 1858, Withers designed St. Helen’s in Little Cawthorpe, Lincolnshire, constructed of red brick with black bands in a geometrical gothic style. This could accommodate 60 parishioners and was lauded as an exemplary example of a well-designed, small church which could be erected economically.

At the same time St. Helen’s was being constructed, Withers would also create two factory buildings in London: one for the famed glass-makers Lavers and Barraud and the other for a building designed to attract a printer/ publisher/ bookseller.

The Lavers and Barraud Stained-Glass Works showed Withers experimenting with color, pattern and texture reflecting the influence of John Ruskin what was perhaps his most daring use of polychromed brickwork. Since that level of detail barely existed in any of his later projects, it was perhaps the client that pushed Withers towards such an inventive and artistic design.

The two-story building located at the corner of Wellington and Exeter Streets in London was intended to have a more industrial feel. This was designed to one building with two purposes. The two story building on the corner held office/ retail space while the adjacent four story section was simpler and more industrial since it was intended for printing presses. By using rounded rather than pointed arches, Withers was able to increase the size of the windows, allowing for much more natural lighting and views into the building from the street. This yellow brick building exhibited restrained polychromy with with its accents of red bricks and stone mouldings. Before the mansard roof was added, the building had a parapet topped with urns at each angle.

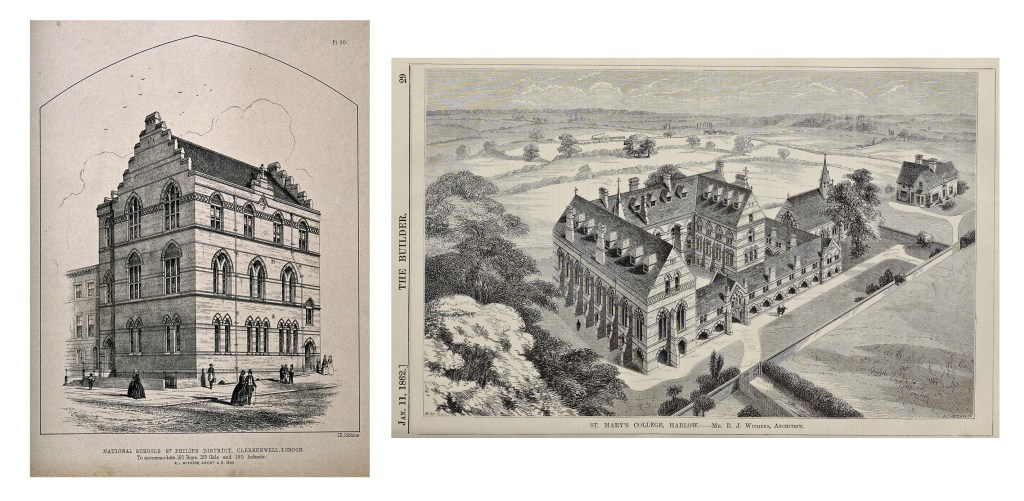

Other buildings designed by Withers with a decidedly Ruskinian influence would include the National School at Clerkenwell and St. Mary’s College at Harlow.

Right: Image from The Builder vol. 28 (1862)

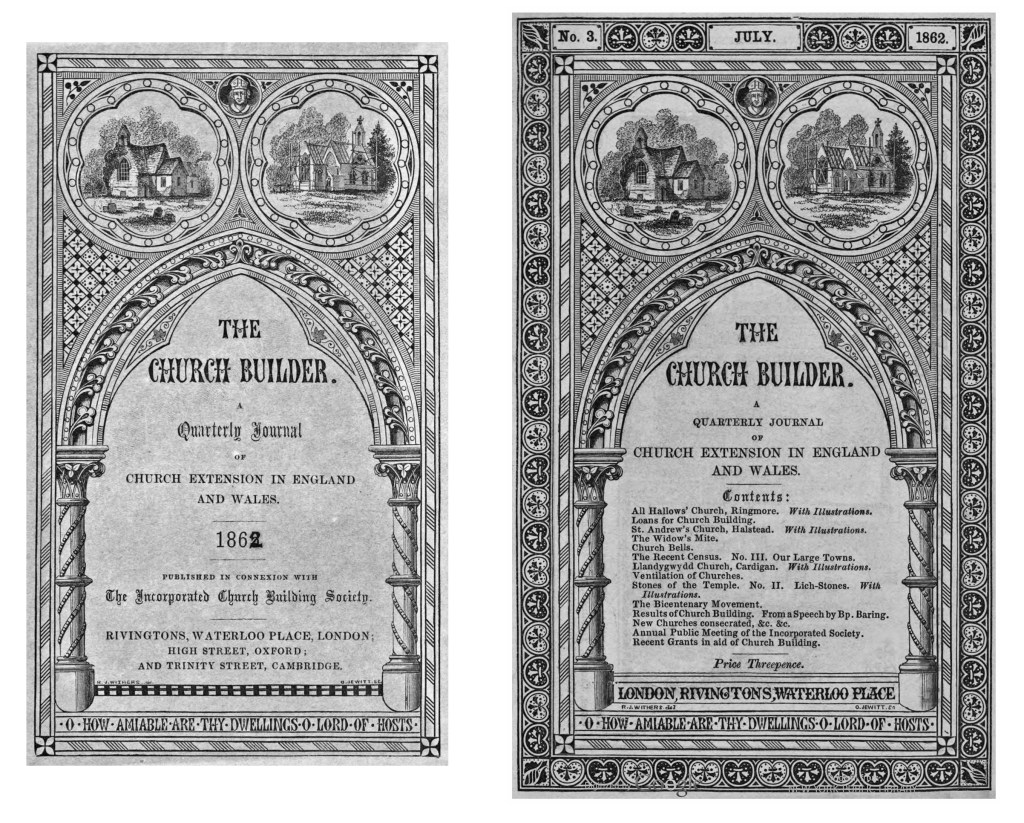

As Withers was showing that he could design in the most current fashions, the main part of his architectural practice was still based in the Ecclesiastical Society and in designing churches, schools, rectories and parsonages for the Episcopal Church. It was perhaps because of that unwavering devotion that he was asked to design the cover of The Church Builder, a quarterly journal published in connection with the Incorporated Church Building Society. Wither designed two slightly different title pages which were used in every issue for almost twenty years beginning with the magazine’s first issue in 1862.

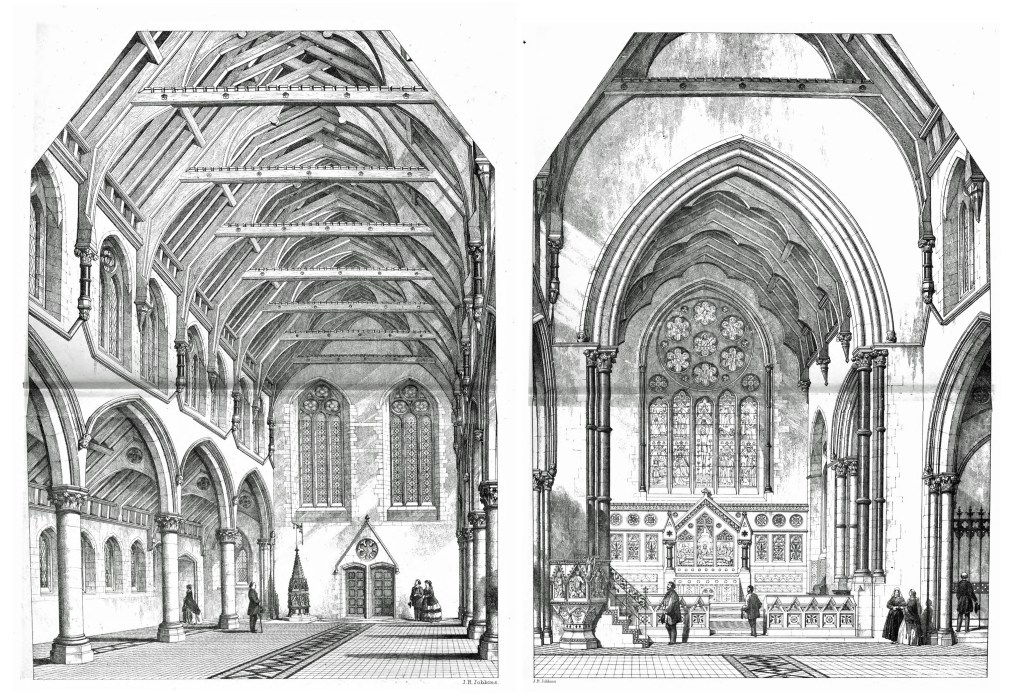

By the early 1860’s not only was Withers career steeped in the archeology and the early English Gothic of the Ecclesiastical Society, but he was proving to be adept at incorporating the Venetian Gothic of John Ruskin and the northern Italian designs of G. E. Street. To this list should also be the influences of Eugene Emmanuel Violet-le-Duc. During the mid-late 1850’s, Violet-le-Duc’s writings were inspiring architects to look to France not only for the foundations of Gothic design in the 12th and 13th centuries, but also into ways of incorporating new materials and technology as a way of bringing Gothic design into the 19th century. In England, a group of young architects led by William Burges, J. P. Sedden and William Nesfield (among others) were challenging the idea of “correct” design and looking to France for inspiration. Withers too would be part of that group. The project which perhaps best exemplified his understanding of that strain of contemporary thought was felt at the Church of the Resurrection in Brussels which he designed between 1862 and 1864.

From Examples of Modern Architecture: Ecclesiastical and Domestic (1870).

In 1864, Withers was elected as a fellow to the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). By that time, he had designed, repaired and/or restored at least forty-five churches, twenty vicarages and rectories, nine schools and seven public buildings. By that time, Withers was not just designing buildings (though not all had gotten constructed) in England and Wales, but also in Belgium, Germany and Canada with even a greater reach in the following years. Besides buildings, he was also a prolific designer of stained glass windows, monuments and tombs, and had designed croziers (pastoral staffs) for the Bishop Thomas Staley of Honolulu and Dr. William Tozer, Bishop of Central Africa.

R.J. Withers would also play a central role in the career of of his younger brother, Frederick Clarke Withers who had emigrated to the United States in 1852 and would become one of its leading ecclesiastical architects. Robert was clearly keeping his brother abreast of his own designs as many (if not most) of Frederick’s ecclesiastical designs were clearly inspired by or borrowed from churches designed by his older brother.

Which finally brings us back to Thomas Wisedell and his training in the office of R. J. Withers. Wisedell was probably hired sometime between 1862 and 1864 and would stay until the fall of 1868. In the next article, we’ll look at buildings designed by R. J. Withers during Wisedell’s apprenticeship and explore some of the changes happening in British architecture and design during that period.