In the fall of 1868, Thomas Wisedell was presented with an opportunity to move from London to New York City to be part of a group of British designers, engineers and craftsmen who had previously immigrated to the United States and were not only creating the modern park movement but also transforming American design. The principle figures who came from Britain included Calvert Vaux, Frederick Clarke Withers, Jacob Wrey Mould, Alfred J. Bloor, George Kent Radford and Robert Ellin among others. Americans who were also part of that group included Frederick Law Olmsted as well as the Hudson River School painters Frederick Church and Jervis McIntee.

What initially brought some of these figures together was the burgeoning world of American landscape design principally centered around Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-1852) in Newburgh, New York in the 1840’s and 1850’s. Beginning with his own property around 1838 which he called “Highland Garden, ” Downing slowly developed a unique brand of landscape design which was rooted in the naturalistic British landscapes of Capability Brown, Humphry Repton and Joseph Paxton. In 1841, he published A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, followed in 1842 by Cottage Residences which was published with Alexander Jackson Davis. Both books were completely tied to contemporary architecture and picturesque landscape design in England. These ideas were furthered through The Horticulturalist, a serialized publication which he began editing in 1846.

By 1848, Downing had issued calls for the establishment of urban parks in American cities and in 1850 he sailed to England in order to visit the parks of Liverpool and London, among others. Besides studying parks, Downing was also looking for a potential architectural collaborator. While attending an exhibition of the Architectural Association of London, he was introduced to a talented young draftsman named Calvert Vaux. The two men clearly shared a common ideology as Vaux was immediately asked to join Downing in Newburgh. Within a few months, the two men partnered to form Downing & Vaux. In 1852, the firm posted an advertisement in a London newspaper seeking an assistant. Upon seeing the ad, Robert Jewell Withers persuaded his younger brother, Frederick Clarke Withers to respond. What may have helped in persuading Vaux and Downing to hire the younger Withers was the Calvert Vaux and R. J. Withers shared a common friendship with the architect George Truefitt (1824-1902). Not only had Vaux and Truefitt trained together in the office of Lewis Nockalls Cottingham (1787-1847), but had also traveled and sketched together while touring France, Belgium and Germany in 1846.

Shortly after F. C. Withers’ arrival in Newburgh, Downing was killed in a steamer accident on the Hudson River. This left Calvert Vaux as the driving force behind the firm’s landscape designs with Withers principally designing the buildings under the new name Vaux & Withers. The two men parted ways in 1856 with Withers staying in Newburgh and Calvert Vaux moving to New York City. Withers soon turned his attention to ecclesiastical buildings, with most of his early churches clearly relying on designs inspired by his older brother, Robert.

Upon moving to New York City in 1857, Calvert Vaux published Villas and Cottages, a highly successful pattern book which, in many ways, updated the earlier books by Downing, while incorporating ideas of John Ruskin and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

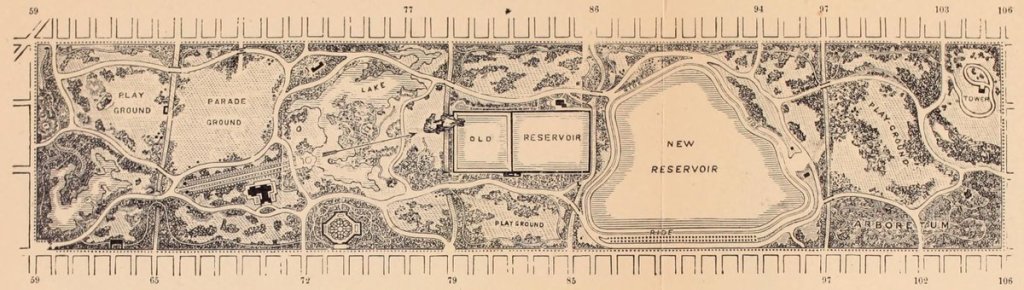

That same year, Vaux also began preparing plans for a competition to design Central Park in New York City. Rather than enter the competition on his own, Vaux made the decision to assemble a team to create a brilliant plan entered under the name, “Greensward.” That team would include Frederick Law Olmsted, Jacob Wrey Mould and Jervis McIntee. Olmsted had worked for the city and had an unparalleled knowledge of the site’s natural terrain and like Downing, had also studied the parks of England. Mould was also working for the city and had already established himself as a generational artistic talent and would be responsible for creating many of the presentation watercolors that would convey the different designs and desired effects. (In fact, Mould and Vaux had both shown drawings at the same Architectural Exhibition of 1850 in London where Downing had met Vaux). McIntee was Calvert Vaux’ brother-in-law but more importantly, he was a successful landscape painter who would also help convey some of the feeling of what that park was to become.

For months, the four men would meet at Calvert Vaux’ home, procuring photos of the various parts of the future park, discussing not only the picturesque aspects of the design, but more importantly, the practical aspects of topography, vegetation and drainage as well as pedestrian and vehicular circulation. Once those functional elements were decided, ideas for buildings, bridges and other architectural features were also designed, giving the competition judges a far greater understanding of the overall concept. No other entrant was this thorough and on April 28, 1858, in was announced that the Greensward Plan had won the competition and the landscape architectural firm of Olmsted & Vaux was born.

The park was basically constructed from south to north and the task of actually grading and creating the sewers and drainage for the park fell to the engineer George Waring. The bridges were the first to be constructed. In most cases, Calvert Vaux seems to have created a general design for each bridge, then (depending on the bridge), either Edward C. Miller or Jacob Wrey Mould would fill in the details. In every case, Vaux never took full credit and the early bridges are either credited to either Vaux & Miller or Vaux & Mould.

Mould was originally from Chislehurst, Kent, England was and was educated at King’s College School in Wimbledon. Throughout the early-mid 1840’s Mould worked for Owen Jones where his most important contributions were in the second volume of Jones’ Plans, Elevations, Sections, and Details of the Alhambra (1845) and later assisted Jones in decorating London’s Crystal Palace in 1851, perhaps the greatest collection of designs from all over the world brought together under one large glass and iron building.

Mould had immigrated to New York City in 1852 and was soon awarded commissions to design All Souls Unitarian Church and a clubhouse for the Union League, though the latter remained unbuilt. In 1857, Mould was hired as an assistant architect for the development of Central Park. After Olmsted and Vaux won the competition to design Central Park, Mould was retained as assistant architect, though his design responsibility were basically equal to Calvert Vaux’.

The early designs for the bridges would blend Italian, Islamic, Moorish, Ottoman and gothic motifs while also experimenting with cast iron. Clearly, Mould’s previous experiences in the London office of Owen Jones had given him a broad understanding of how to synthesize disparate styles into a unified design.

Though bridges and buildings would be constructed throughout the park, it was at the mall and terrace where Vaux and Mould created a sculptural program based on three-dimensional depictions of scenes found in nature that would have long-term impact not only on later landscape architecture, but also on designs for domestic, ecclesiastical and commercial architectural features. What made these features so remarkable was not only their design, but also their execution. Though there were stone cutters and carvers in the United States, it was common for more important commissions to be carved in Europe and sent back to be installed. In order to execute the complex carvings at the terrace, James Whitehouse and Robert Ellin, who had recently immigrated from Scotland and England, respectively, were hired to carry out the sculptural panels designed by Mould. Both Whitehouse and Ellin would go on to be pioneers in the American wood and stone carving. Robert Ellin would later form a partnership with William Kitson and their firm quickly rose to prominence gaining some of the most prestigious commissions of the late nineteenth century. Both Olmsted and Vaux would continue to use his services throughout the remainder of their careers.

Right: Carved panel by James Whitehouse and Robert Ellin, ca. 1867.

While Olmsted and Vaux were busy transforming Central Park from an idea on paper into a physical reality, the pair soon gained commissions for parks in Brooklyn (1865) and Buffalo (1868), as well as the design for the campus and grounds at University of California at Berkeley (1866) and Gallaudet College in Washington, D.C. (1866) and for the planning of the entire suburb of Riverside, Illinois (1868). Besides these, there were also numerous smaller commissions and by 1868 the firm of Olmsted & Vaux was already designing on a national scale.

With this rapid growth and need for a greater understanding of urban park design, Calvert Vaux began research for a book he was about to write on the subject. With this in mind, Vaux and George Kent Radford (1826-1908), a British civil engineer working with Olmsted & Vaux, sailed for Europe in August 1868 to study urban parks and zoos, rendering plans and drawings for the potential book. Two of their largest commissions, Central Park in New York City and Prospect Park in Brooklyn (as well as a series of smaller parks in each city) were well underway. With much of the grading and planting in place, Vaux was about to turn his attention to the numerous architectural features required in those parks and was looking to hire a young associate architect. What may have been at issue was that Vaux’s long-time assistant, Alfred J. Bloor, had resigned in 1867 and Jacob Wrey Mould, who was working with Vaux, was not actually one of his employees, but was the assistant architect in New York City’s Parks Department.

By October, Vaux and Radford were in London studying various public and private parks and gardens while making multiple trips to the Crystal Palace School of Art, Science and Literature. While in London, Vaux also visited his sister Catherine who had married the architect Robert Jewell Withers in 1854. It was during that trip in 1868 that Vaux and Radford were introduced to Thomas Wisedell, a talented young draftsman in Withers’ office with a gift for creating architectural ornament. Vaux had apparently asked Wisedell to make drawings of Chiswick and Regent’s Park. Having been quite impressed with Wisedell’s abilities, Vaux soon persuaded him to immigrate to the United States to assist in designing park structures.

Wisedell would have already been familiar the architecture of Vaux & Withers which Robert would have surely been showing to his colleges. In 1867, Robert Withers had sent sent photos of their work to the Ecclesiastical Society to be reviewed and later that year, donated a copy of Calvert Vaux’ Villas and Cottages to the Royal Institute of British Architects. Over the next few weeks, Wisedell prepared to sail with Vaux and Radford, and on November 18, 1868, the three men arrived in New York City.

When Vaux arrived back in New York, he resumed work on designing structures for Central Park in New York City as well as Prospect Park and Washington Park (now Fort Greene Park) in Brooklyn, New York. Within months of his arrival, Wisedell was already being paid by the Central Park Board of Commissioners for “architectural services.” Though Wisedell was technically working for Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted, the reality was that it was the park’s assistant architect, Jacob Wrey Mould (1825-86) who ran the architectural office for Central Park. Though the types of building and their placement withing the landscape were dictated by F.L. Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, it was under Mould that most of the designs were created.

Right: Mineral Spring House (1867-1868)

Throughout the 1860’s, Vaux and Mould would design and construct the mall and terrace (the park’s principal architectural feature), the Casino (ladies pavilion) and pergola overlooking the mall and the Belvedere. Other smaller building which had only recently opened were the Boys Cottage, the Girls’ Cottage, the Children’s Cottage, the Music Pavilion and the Mineral Spring House. The exterior retaining around the perimeter of the park was also under construction and the Scholars’ Gate at the corner of Fifth avenue and Fifty-Ninth street had just been redesigned.

When Thomas Wisedell arrived in late 1868, the mall in Central Park was just being completed, with the Minton tiles being installed in the terrace with other decorative features such as the granite niches being desined in 1869 . Much of the grading and planting in the southern half of the park had been completed and numerous buildings were either under construction or in their early stages of design. The Belvedere was almost completed though working drawings for its interior features and tower were created at that time. Buildings which had only recently been commissioned and would most likely have been designed with Wisedell’s assistance include the unbuilt projects for a Paleozoic Museum, a temporary building used for the sport of curling and a redesign of the Merchants’ Gate at Eighth Avenue and Fifty-Ninth Street.

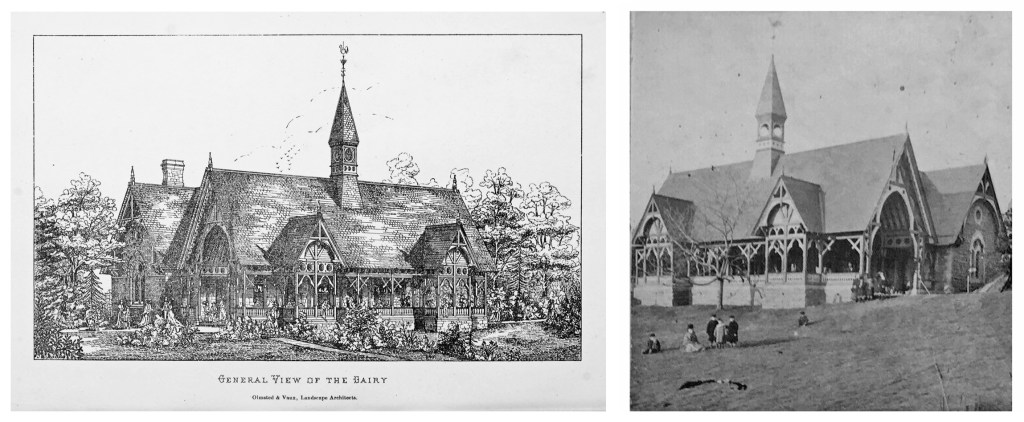

Right: Central Park Dairy, Stereoview image, ca. 1875.

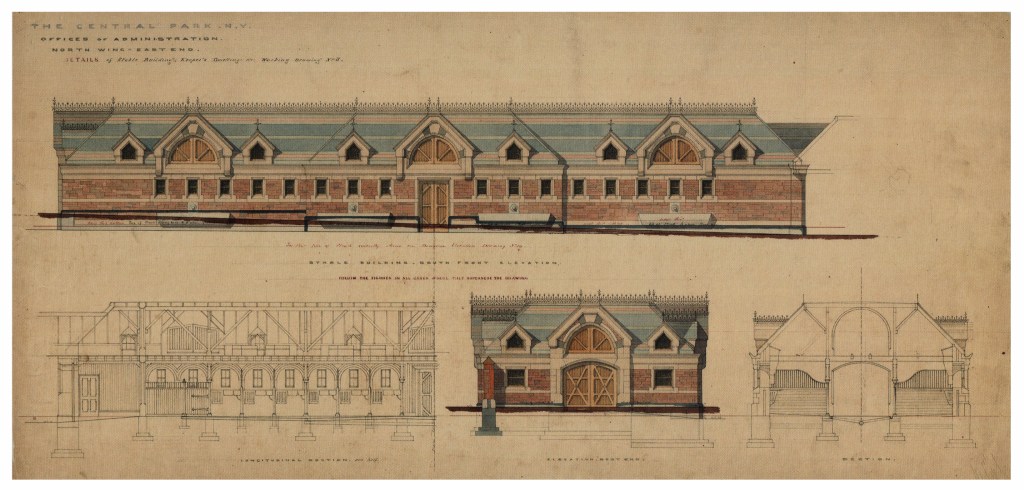

The only project that that is known to have relied on Wisedell’s assistance was the Dairy which had been designed by Calvert Vaux in 1869 and in fact, it was Wisedell’s rendering which was published in Central Park’s Thirteenth Annual Report. Another project from that period which would have also benefited from Wisedell’s experience with gothic detailing would have been with the designs of the administration building which included stables and sheds as well as a “Keeper’s Dwelling.”

Other projects that date to Wisedell’s time in Central Park include much of the remodeling of the old arsenal building at 64th Street in the park. This was quite an extensive remodeling since it was to house park offices as well as a temporary home for the Natural History Museum. The earliest designs for the Metropolitan Museum of Art also date from that period.

Since the Dairy was the one building that definitely relied on the talents of Thomas Wisedell, it will be the subjuct of the next post (2c continued).

Further Reading:

- Alex, William and Tatum, George B., Calvert Vaux: Architect and Planner (New York: Ink, Inc., 1994).

- Brenwell, Cynthia S., The Central Park: Original Designs for New York’s Greatest Treasure (New York: Abrams, 2019).

- Kowsky, Francis R., The Architecture of Frederick Clarke Withers and the Progress of the Gothic Revival in America after 1850 (Middleton, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1980).

- Kowsky, Francis R., Country, Park & City: The Architecture and Life of Calvert Vaux (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).

- Roper, Laura Wood, F.L.O.: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973).

- Rybczynski, Witold, A Clearing in the Distance. Frederick Law Olmsted and America in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Scribner, 1999).

- Schuyler, David, Apostle of Taste: Andrew Jackson Downing 1815-1852 (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996).