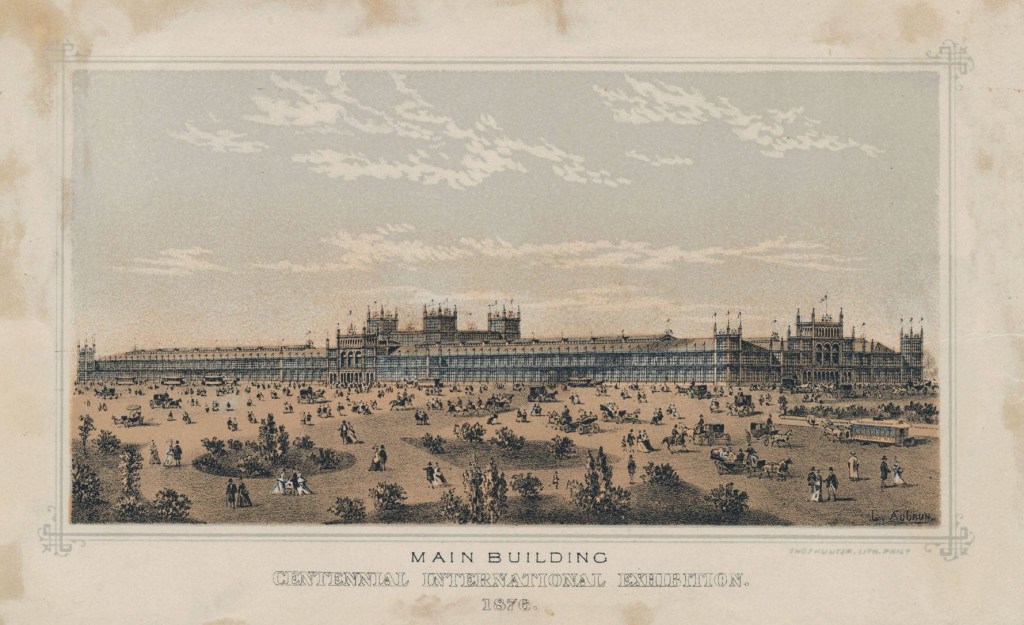

With the centennial of the founding of the United States approaching in 1876, President Ulysses S. Grant signed a bill in March of 1871 to establish a commission charged with creating an exposition to commemorate the event. Philadelphia was chosen as host and on April 1, 1873 a formal committee was appointed and a competition to find suitable plans was announced. For Thomas Wisedell, the timing could not have been better. By that time, the designs for Prospect Park and Washington Park in Brooklyn had been completed and most of the architectural features for the Buffalo parks would not be designed until the summer of 1874. So for most of 1873, Wisedell worked as a draftsman in the office of Vaux & Radford.

Following the termination of his partnership with Frederick Law Olmsted in early 1873, Calvert Vaux soon formed a partnership with George Kent Radford, a British civil engineer who had worked with Olmsted & Vaux at Central Park, Prospect Park and in Buffalo and had accompanied Vaux on his 1868 trip to Europe when the two men were introduced to Thomas Wisedell in the London office of Robert Jewell Withers. What may have been the first project designed under Vaux & Radford was for their entry into the competition for the Centennial Exposition and it was their entry which garnered the most attention and was declared the winner — though ultimately not constructed. Thomas Wisedell would play a crucial role in Vaux & Radford’s designs for the second round of that competition, but before that second round, Wisedell had partnered with James M. Farnsworth (1847-1919), an architect who had joined Vaux’ office in 1872, and submitted an entry under the firm name of Wisedell & Farnsworth.

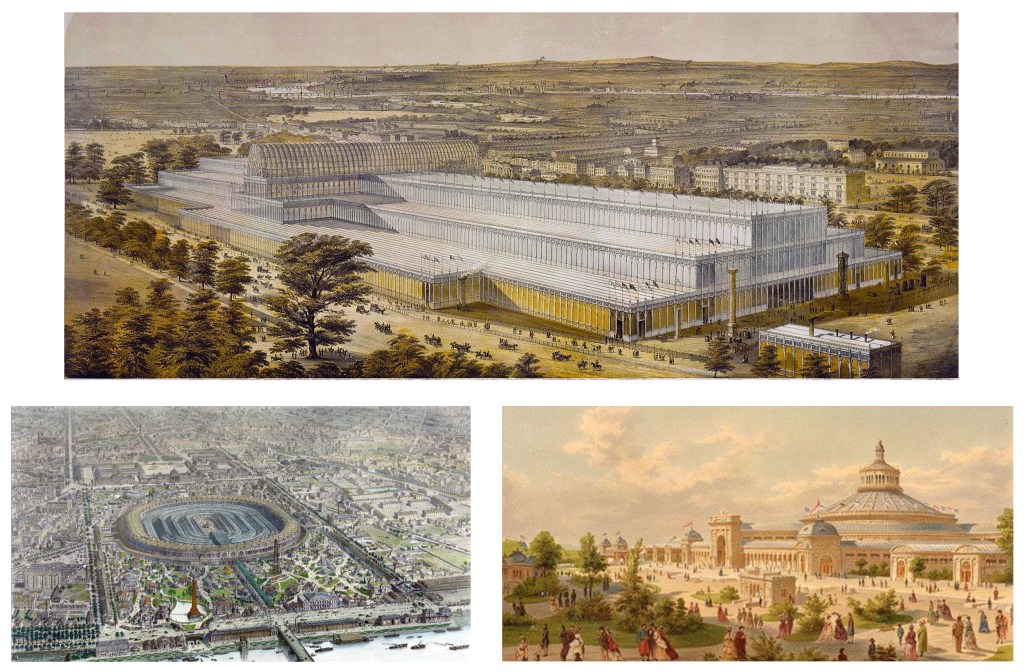

Bottom Left: Exposition Universelle, Paris, 1867. Bottom Right: World’s Fair Exposition, Vienna, 1873.

For the first round of the competition, forty-three entries had been submitted by July 15, 1873 and within days, all of the plans were put on public display at the Old University Building in Philadelphia. Almost all of the entries had relied on previous exposition in London, Paris and Vienna for their inspiration. On August 8th, the committee chose ten of those who were then invited to participate in the second round. The plans of Wisedell & Farnsworth were not chosen. All plans were then returned to their architects. Because of this, very few plans from that first round actually survive.

A brief description of most of the entries was published in the New York Times. Wisedell & Farnsworth’s was known as plan number 18 and submitted under the name “Princeton.” This was described as having been planned along similar lines to the building erected for the 1851 exposition in London as “a long building with transepts and internal galleries”with a “Memorial Building in the center with dome in a Gothic style.” Basically, the “Memorial Building” was to be designed as a permanent structure which would serve as an art museum after the close of the exposition while the rest of the building was to be constructed in materials (like cast iron and glass) which could easily be removed.

What was the most important feature of Wisedell & Farnsworth’s submission was perhaps the Gothic dome. Traditionally, domes were designed in early Christian (or Byzantine), Islamic or renaissance styles. In the early 1870’s, the idea of constructing a dome in a Gothic style was was being debated in the international press, especially in England, Germany and the United States.

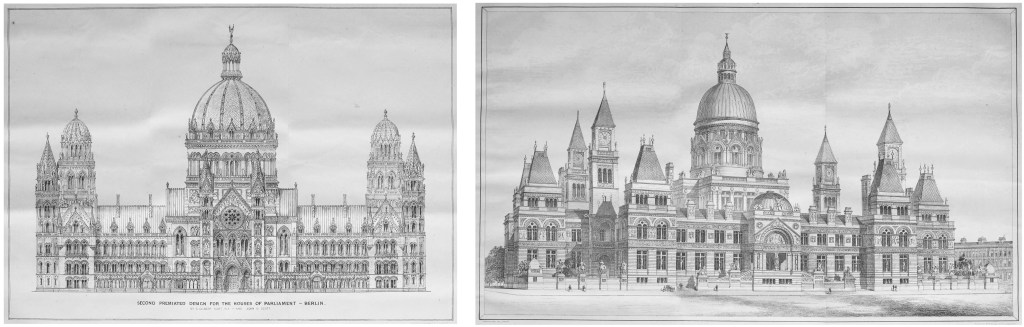

With the formation of the German Empire in 1871 following the Franco-Prussian War, Berlin was established as its capitol city. Later that year, an international competition was announced to design a new parliament building to be called “The Reichstag.” Though quite a few entries produced Gothic designs, it was the submissions by the British architects Sir George Gilbert Scott and Edward W. Godwin which displayed the grandest possibilities within the style.

Right: German Parliament Building (Reichstag). Competition design by Edwin W. Godwin. The Architect vol. 8 (July 13, 1872).

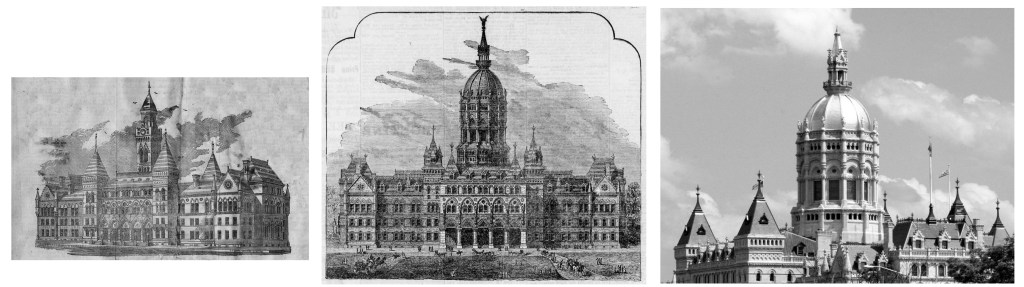

At the same time as the Reichstag competition, and a little closer to Philadelphia, the legislature of the State of Connecticut had announced a competition to design a new state capitol building to be erected at Hartford. The competition had produced plans that heavily relied on contemporary municipal buildings in England, almost all of which were dominated by towers rather than domes. The competition was won by Richard M. Upjohn, however, his appointed was soon undermined by James G. Batterson, one of Upjohn’s competitors but also who was given the contract to erect the capitol building.

The battle between Upjohn and Batterson is far too convoluted to discuss here in full detail. However, the short version was that Batterson had entered the competition with his long-time assistant, George Keller (under the name Batterson & Keller). After the second round, Upjohn was officially declared the winner, but only for the building’s exterior. This still gave Batterson a way to undermine the entire competition by offering a completely new plan. Since George Keller had left Batterson to begin his own independent career, Francis H. Kimball was then hired to draw up new plans and elevations which were based on the Reichstag competition — complete with gothic dome. Though Batterson was not successful in upending Upjohn’s appointment, he was successful in having Upjohn altering the building’s plan and replacing the clock-tower with a Gothic dome. All of that was happening at the same time that Wisedell & Farnsworth were designing their entry for the Centennial Exposition competition, giving an insight into some of the design ideas that permeated architectural thought of the early 1870’s.

Center: Connecticut State Capitol, redesigned with dome, mid-1873.

Right: Connecticut State Capitol. Detail showing the dome as constructed.

Wisedell & Farnsworth unfortunately did not make it past the first round. The next posting will show how Calvert Vaux fully understood Thomas Wisedell’s remarkable capabilities as draftsman and utilized those talents during the second round of the competition to design the Centennial Exposition.

Further Reading:

- Report of the Committee on Plans and Architecture, to the U.S. centennial Commission. Nov. 1, 1873 (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1873).

- The National Celebration of the Centennial Celebration of the United States by an International Universal Exhibition, to be Held in Philadelphia in the Year 1876 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1873).

- The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted. Volume IV: The Years of Olmsted, Vaux & Company 1865-1874 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992).

- Alex, William and Tatum, George B., Calvert Vaux: Architect and Planner (New York: Ink, Inc., 1994).

- Kowsky, Francis R., Country, Park & City: The Architecture and Life of Calvert Vaux (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).