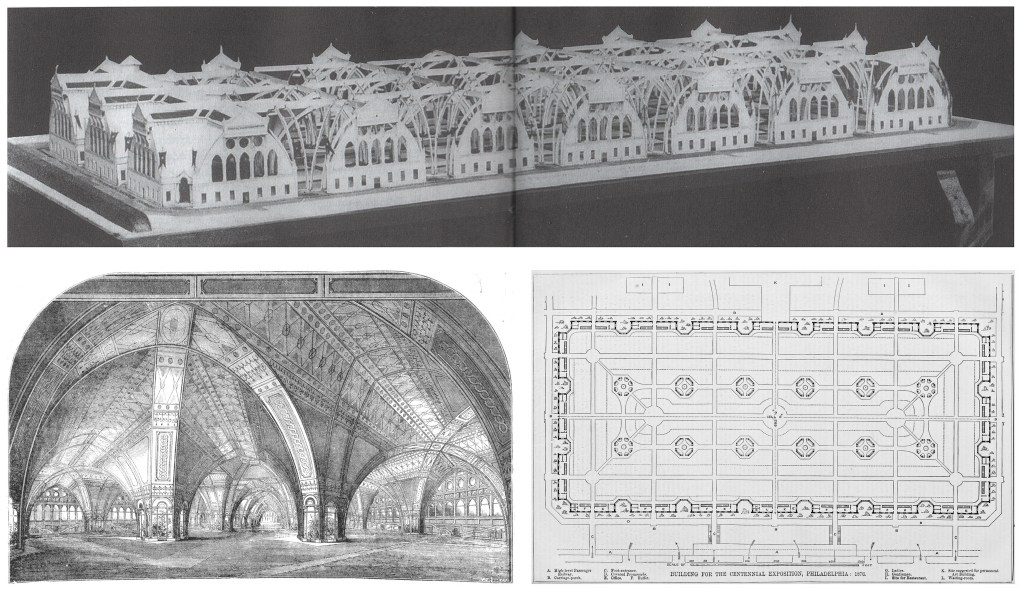

Though Thomas Wisedell and James Farnsworth were unsuccessful with their entry for the Centennial Exposition competition, Calvert Vaux and George Kent Radford were chosen as one of ten architectural firms invited into the second round. During the first round, Vaux & Radford had created an ingenious plan of twenty-one interconnected, square pavilions, each measuring about 240 feet in diameter. Rather than having an draftsman from inside his architectural firm draw the perspective and plan for the competition, Vaux hired Alfred Smith, a London architect whom he had known before immigrating to the United States in 1850 and who happened to be visiting New York in 1873.

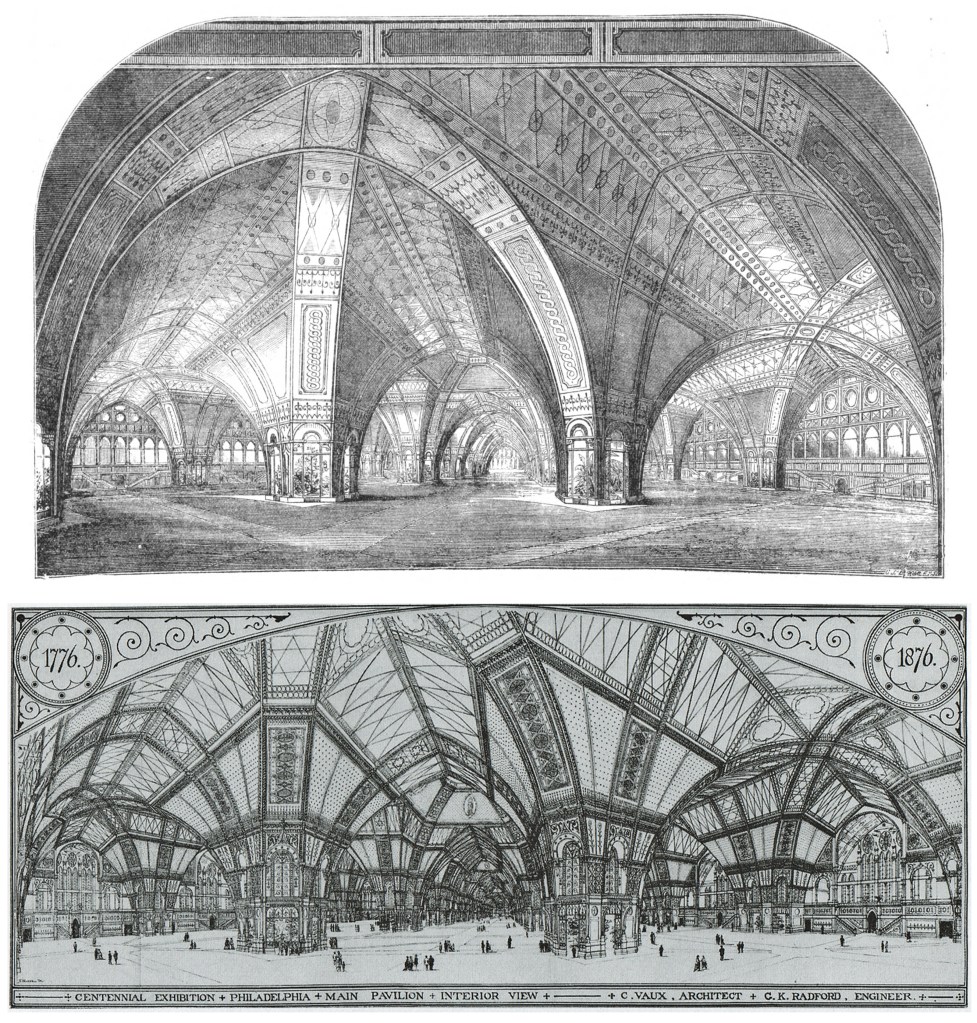

Bottom: Interior perspective and plan drawn by Alfred Smith and submitted by Vaux & Radford from the first round

of the Centennial Exposition competition. Published in The Builder (Dec. 6, 1873).

Vaux & Radford’s plan was quite ingenious with its blend of aesthetics and engineering. Stylistically, it combined early Gothic and Queen Anne details while its engineering was rather advanced in the way it was based on a repetitive, modular system that used few parts which could be manufactured in bulk and would have been easy to assemble and dismantle. A weakness in the eyes of the judges, however was that it did not incorporate a section of the building to be called “Memorial Hall” that was to stay permanent after the exposition had ended, as stipulated in the competition rules.

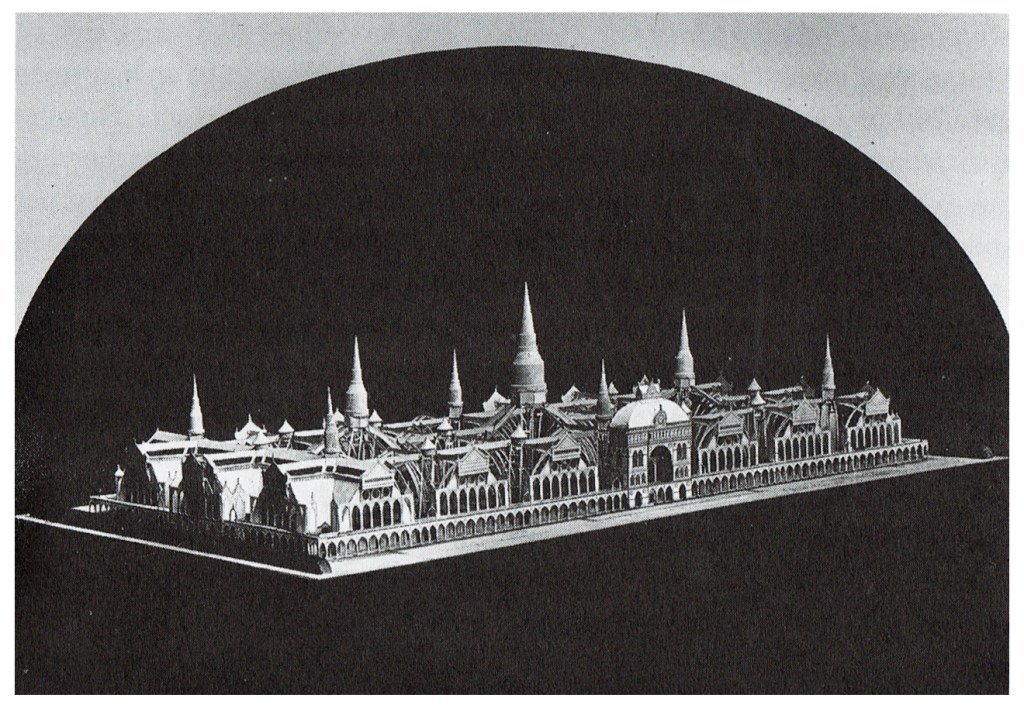

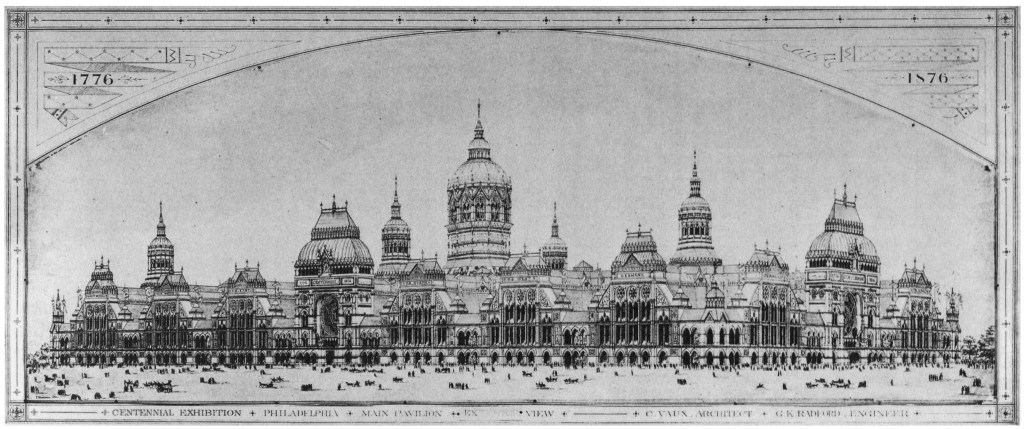

For the second round, Vaux and Radford had maintained much of the same plan but had added a central, grand entrance as well as a covered, arcaded walk around the perimeter of the building. Also added were spires which meant a structural change, greatly increasing the the number of parts that had to be fabricated. Though this plan was highly lauded, it was deemed inadmissible since it still did not incorporate a section of the building which was to stay permanent, even though Vaux & Radford had laid out clear and rational reasons why the exposition building and the Memorial Hall needed to be designed as separate structures.

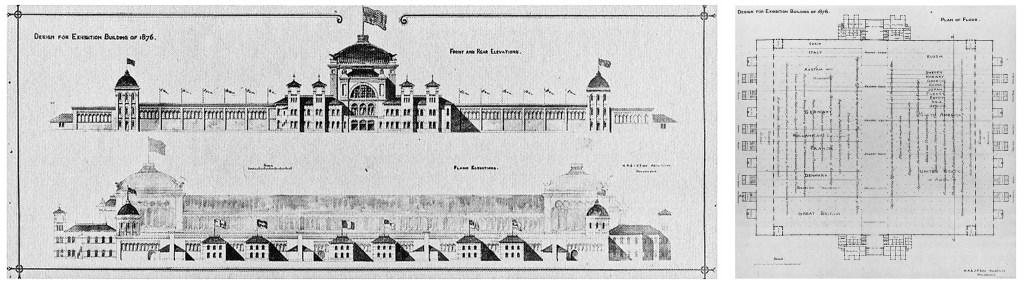

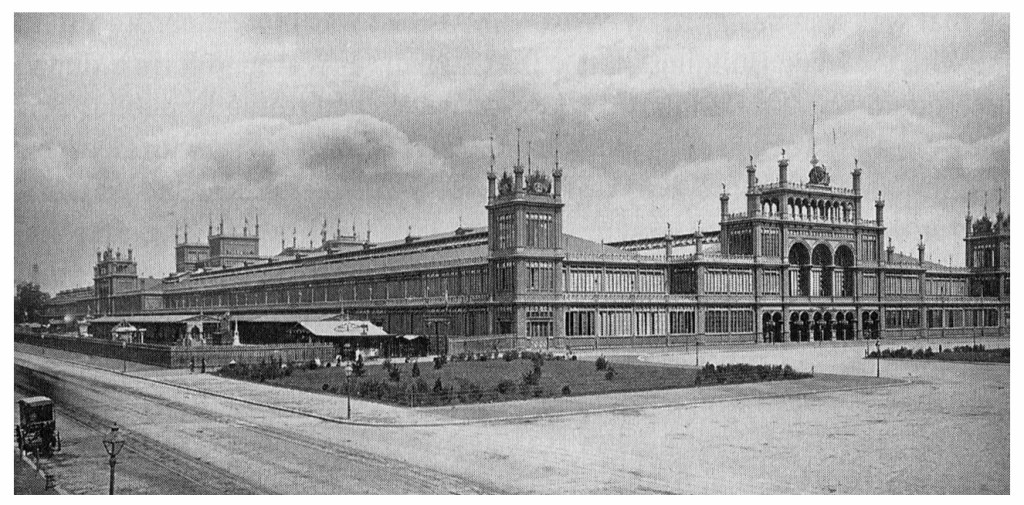

Though they were technically disqualified and could not be awarded a prize, the exposition planners made the decision that Vaux & Radford’s plans from the first round of the competition should be merged with the plans submitted by architects Harry A. and James P. Sims of Philadelphia. Architects Henry Petit and Joseph Wilson were asked to combine the plans though it was clear that both men did try to persuade the commissioners that the building did not have to be redesigned and that the plans Vaux & Radford as well as Henry and James Sims were chosen. It was also clear that to two men felt that Vaux & Radford’s scheme was clearly superior. In the end, Vaux & Radford declined to participate in the scheme and the building was ultimately designed by Petit and Wilson, as a separate building away from Memorial Hall which designed by Herman Schwartmann. As it turned out, since Memorial Hall was to be a permanent building, its design was subject to state and city approval while the exhibition building was controlled solely by the Centennial Exposition Committee and the two building should never have been designed together.

As for Wisedell, Vaux had him create a group of drawings which included an interior perspective, an exterior elevation and a building plan which have actually caused a bit of confusion among historians. Among the documents submitted to Congress in November 1873 was Wisedell’s perspective rendering which had been drawn after the second round of the competition and has been used to understand Vaux & Radford’s entries while disregarding the earlier perspective rendered by Alex Smith. Much of that confusion arose from the fact that Smith actually took his drawing back to London where he later published it in the British architectural journal, The Builder in December 1873. By then, the competition had ended and since Vaux & Radford’s plan would be altered anyway, there is no evidence that Vaux objected to Smith’s decision to publish the rendering. Since Vaux no longer had the drawing from the first competition, that might explain why he sent Wisedell’s drawing to Congress instead (though that is obviously just a hunch).

Wisedell’s renderings were created after the second round when it was decided to combine the designs of Harry and James Sims with the pavilion plan of Vaux & Radford from the competition’s first round. Rather than using Sims’ designs, however, these renderings reflected Vaux & Radford’s second round plans while utilizing the Gothic domes and towers from the first round entry by Wisedell & Farnsworth. Since both of those designs were rejected by the Centennial Commission, these were created as a theoretical exercise and in the words of Calvert Vaux, Wisedell’s renderings were published in the September 1874 issue of the New York Sketchbook of Architecture, “simply as an architectural study.”

Thomas Wisedell had clearly reworked Smith’s rendering to reflect the design changes. Smith’s drawing from the first round of the competition shows that Vaux & Radford were relying on abstract and geometric details perhaps inspired by the later glass and cast-iron building by Owen Jones. Wisedell’s drawings clearly reflect stylistic choices that can be found in the buildings of Robert Jewell Withers especially in the window designs which echoed those at the churches in Coxhoe and Lampeter. Wisedell also incorporated floral panels based on designs by Christopher Dresser similar to those he designed for Calvert Vaux at the Concert Grove in Prospect Park, Brooklyn. (This thought will become more apparent in a later posting). In the end, it is Alex Smith’s rendering that should be used to understand the intentions of Vaux & Radford while Thomas Wisedell’s should be put in the context of a theoretical exercise which represented a snapshot of the technological and stylistic progress that was being made during the early 1870’s.

Further Reading:

- Report of the Committee on Plans and Architecture, to the U.S. centennial Commission. Nov. 1, 1873 (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1873).

- The National Celebration of the Centennial Celebration of the United States by an International Universal Exhibition, to be Held in Philadelphia in the Year 1876 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1873).

- The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted. Volume IV: The Years of Olmsted, Vaux & Company 1865-1874 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992).

- Alex, William and Tatum, George B., Calvert Vaux: Architect and Planner (New York: Ink, Inc., 1994).

- Giberti, Bruno, Designing the Centennial: a History of the 1876 International Exhibition in Philadelphia (Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2002).

- Kowsky, Francis R., Country, Park & City: The Architecture and Life of Calvert Vaux (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).