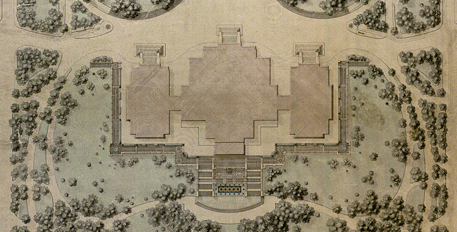

Rendering by Thomas Wisedell, September 1874.

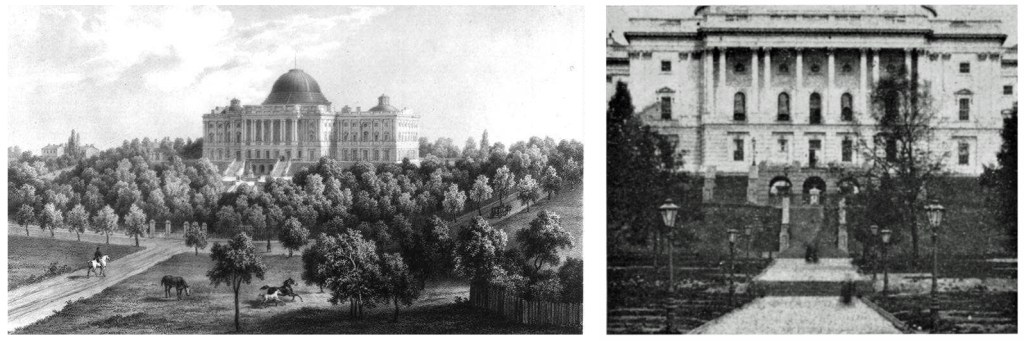

While Thomas Wisedell was designing the architectural features for the East Plaza in the summer of 1874, he was also working out multiple studies and perspectives for a suitable design of a terrace to wrap around the north, south and west sides of the U. S. Capitol building. The existing terrace was designed by Charles Bullfinch in the mid-1820’s with a pair a stairs leading to a lower terrace.

Right: Photograph of western terrace ca. 1870.

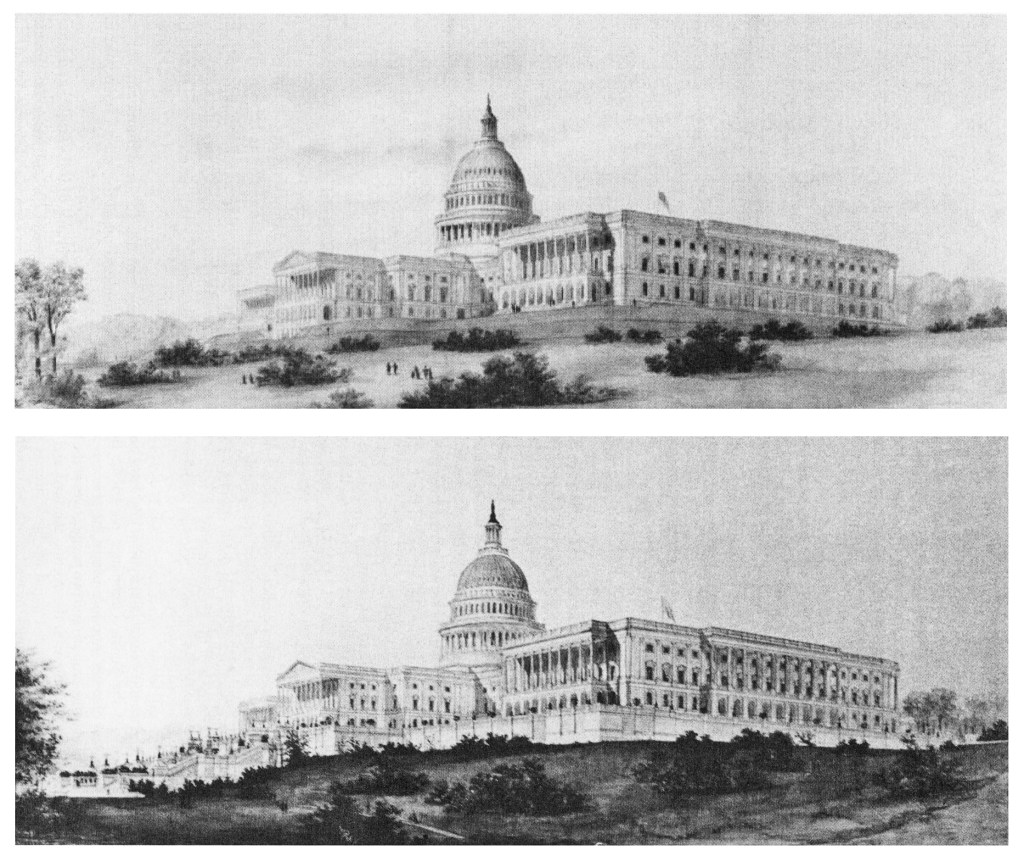

The need for an expanded terrace had become quite apparent following the erection of new house and senate wings in the 1850’s as well as the massive cast iron dome which had been completed in 1865. Besides those features, architect Thomas Ustick Walter had also planned a large expansion of the Library of Congress which at that time was housed in building’s western wing. Walter’s plans had called for for extending the library westward with a newly designed pedimented portico, echoing the main entrance on the east side. After consulting architects Thomas Ustick Walter and Edward Clark as well as engineer Montgomery Meigs, Olmsted tasked Thomas Wisedell’s with designing an expanded terrace that would accommodate that library expansion while properly anchoring the entire building to the edge of the hill without detracting aesthetically.

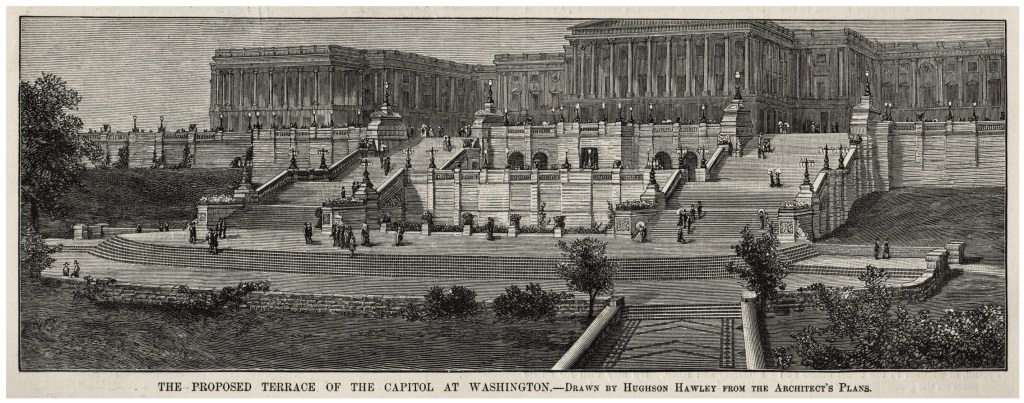

Bottom: View of Capitol with proposed terrace, watercolor by Thomas Wisedell, 1875.

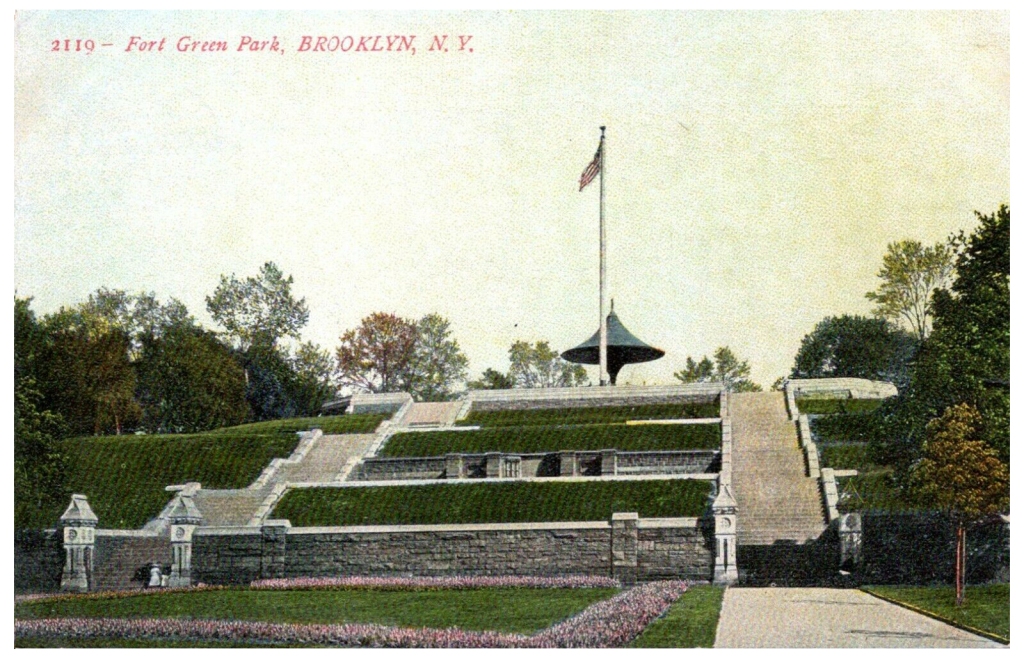

The overall size of the terrace was 60 feet wide and 1400 feet long wrapping round three sides of the Capitol. In slight contrast to the Renaissance/ Baroque style of the building the design of the terrace and stairs had Wisedell’s trademark Indo-Islamic elements combined with Romanesque arching. In scale, proportion and layout, the terraced stairs were quite reminiscent those found at Washington Park in Brooklyn which had been designed by Olmsted & Vaux with Thomas Wisedell in 1873 and was currently under construction. Augmenting the terrace were planters with floral carvings mirroring the designs Calvert Vaux and Thomas Wisedell had designed in 1872 for the Concert Grove in Prospect Park, also in Brooklyn and whose construction was completed in 1874. This timing was quite crucial since it allowed for Senator Justin Morrill of Vermont (who was the principle member of congress overseeing the construction of the Capitol grounds in Washington) to actually visit the two parks in Brooklyn to get an idea of how Olmsted’s vision would translate into marble and stone.

Mirroring the design for the steps at Washington Park (later known as Fort Greene Park) made a lot of since the two projects had similar programs as both were meant to be monumental on a national scale. Also, both projects used terraces to shore up hillsides while disguising architecture features within: underground offices in the case of the U.S. Capitol and the Martyrs Tomb in the case of Washington Park.

Funding for the construction of the terrace would stall until the early-mid 1880’s though Olmsted and Wisedell would continue to refine the scheme throughout the late 1870’s. In the summer of 1879, Wisedell formed a partnership with Francis Kimball (1843-1919) and the two men immediately rose to top of the architects specializing in theatrical design. That same year, Wisedell moved to Yonkers, NY while also beginning to suffer health problems which hampered his ability to complete projects in a timely manner. This was especially true with the his continued involvement with redesigning the Capitol steps and terrace as well as the summerhouse and stonework on the western side of the Capitol grounds. Unfortunately, Wisedell would not live to see the construction of the Capitol terrace and steps as he would succumb to complications from Bright’s disease on July 31, 1884 at only 38 years of age.

In 1885, it was decided not to make the addition to the Library of Congress in the western wing and the following year, Congress began appropriating funds for the construction of the terrace. Because of that change (among others) Olmsted had the terrace and steps slightly redesigned by architect Howard C. Walker of Boston (with input from architect H. H. Richardson as well). Though the materials were changes and the style was simplified, most of Thomas Wisedell’s overall plan was still retained and he should be noted as one of the principle architects in history of that project.

Further Reading:

- Allen, William C., History of the United States Capitol: a Chronicle of Design, Construction and Politics (Washington, D.C.: The Government Printing Office, 2001).

- Documentary History of the Construction and Development of the United Stated Capitol Building and Grounds (Washington, D.C.: The Government Printing Office, 1904).

- The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted. Volume VII: Parks, Politics and Patronage 1874-1882 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).

- The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted. Volume VIII: The Early Boston Years 1882-1890 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013).

- Brown, Glenn, History of the United States Capitol vols. I and II (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1900, 1903).

- Keim, DeBenneville Randolph, Keim’s Illustrated Handbook. Washington and Its Environs: A Descriptive and Historical Hand-Book to the Capitol of the United States of America. 6th ed. (Washington, D.C.: DeB. Randolph Keim, Publisher, 1875).

- Weeks, Christopher, AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C., 3rd ed. (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994).