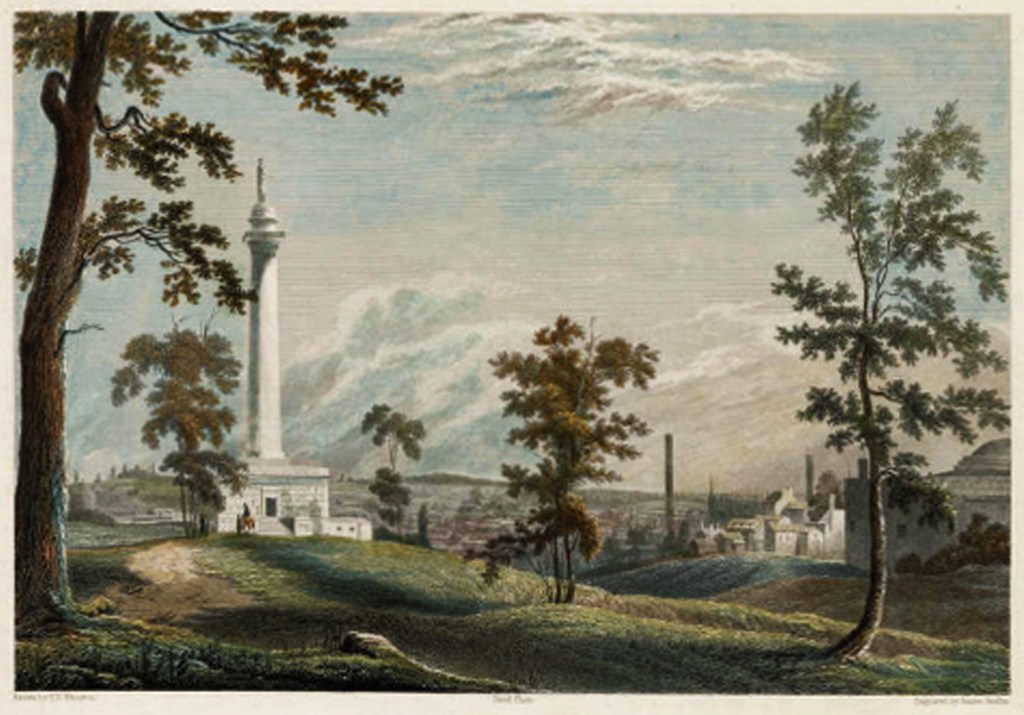

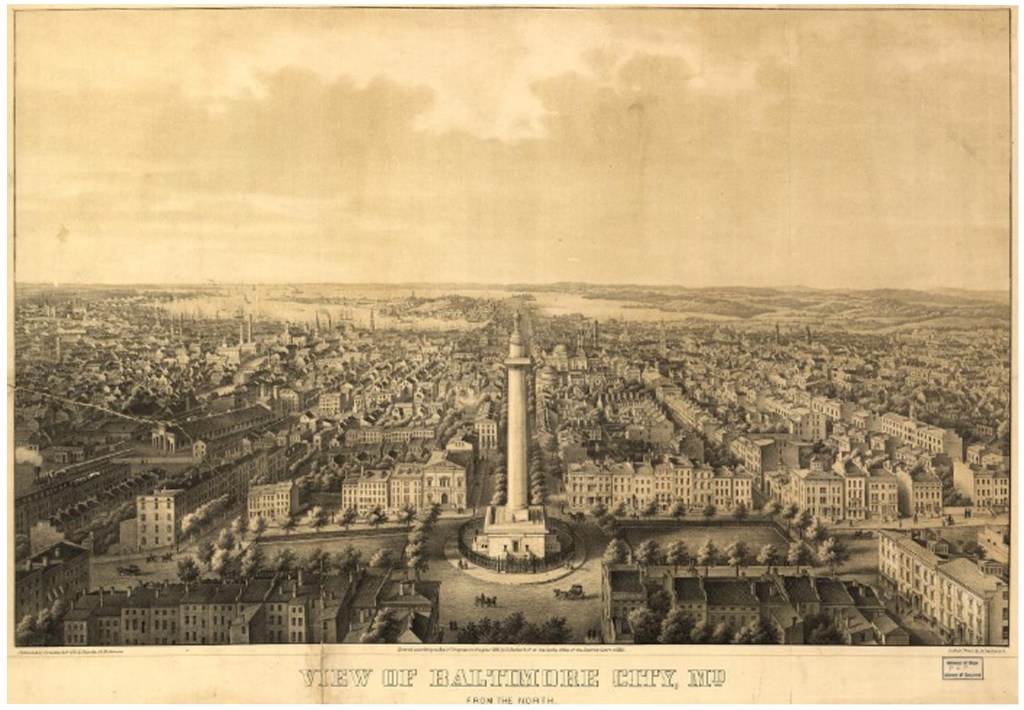

In 1875, members to the Baltimore City Council sought $40,000 towards the renovation of the four parks that served as approaches to the Washington Monument at Mount Vernon Square. The monument was originally designed by Robert Mills and constructed between 1815 and 1829 to honor George Washington and was erected on John Eager Howard’s estate on high point just north of the city where it overlooked Baltimore as well as the harbor below. The city soon expanded around and beyond the monument, naming the neighborhood Mount Vernon Place as a reference to George Washington’s home overlooking the Potomac River in northern Virginia. When the streets were laid out in 1831, the city established four “reservations” or small parks consisting of unadorned flat lawns with rows of trees and cast and wrought iron fencing around the perimeter of each, giving the monument broad approaches while not allowing buildings to encroach too closely.

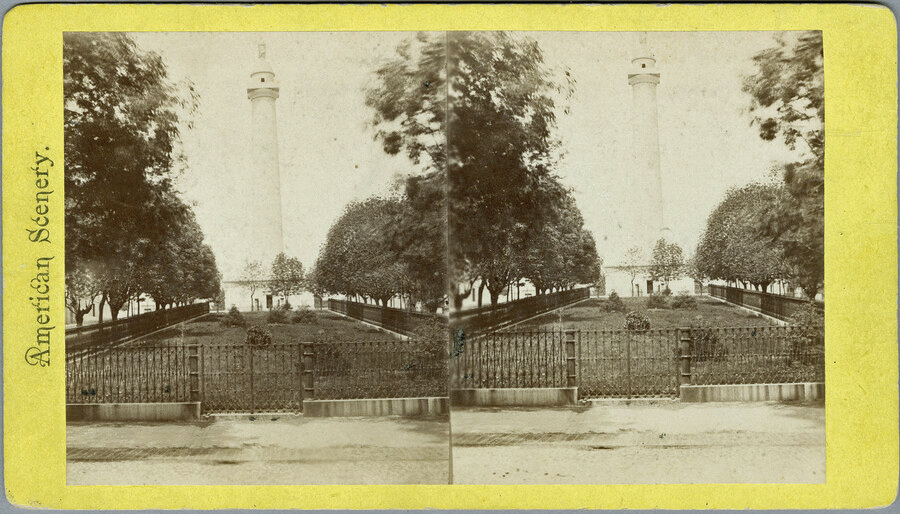

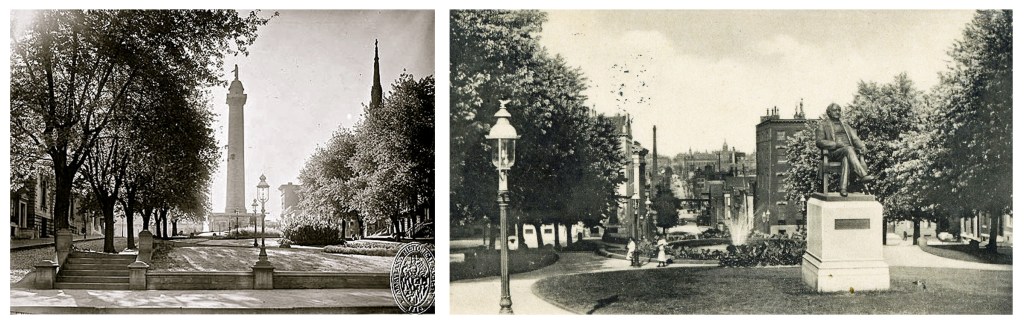

https://www.mdhistory.org/resources/stereoview-of-south-washington-place-and-washington-monument/

Throughout late 1875 and early 1876, three members of the city council studied the issue of remodeling the parks. Their initial idea was to install stone perimeter walls with fountains, walks and flowerbeds. Basically, they were wanting strait , central paths through each , with plantings on either side. At either end of each park were to be fountains on the outside of the perimeter walls. With this initial scheme in mind, the city passed an ordinance to improve the parks at the October 2nd meeting and set aside $12,000 to get the project started.

Within weeks of that meeting, Frederick Law Olmsted was contacted by Thomas Lanahan, who chaired the three member committee. Olmsted had already been working in Baltimore earlier that year, consulting on transforming “Clifton,” the large estate owned by the financier and philanthropist Johns Hopkins, into the grounds for his newly formed college. That project however, was quickly abandoned as the college president, Daniel Coit Gilman, opted to locate the institution closer to downtown.

On December 23rd, Olmsted responded with a lengthy letter to Lanahan where he included a thoughtful criticism of the plan submitted by the committee while suggesting a new design for each park. His first impression of the site was that the simple and chaste design of the parks was quite appropriate for the monument’s solemnity and simplicity but acknowledged the need to upgrade the parks based on the development of the neighborhood surrounding the monument. Though he liked the simplicity of the commissioners plan, he did note that it would require constructing almost 3000 linear feet of wall and in regards to the east and south parks especially, the walls would require deep foundations due to the sloping sites, thus placing a lot of cost underground. His main criticism, however, was that the commissioners plan had treated all of the park the same creating a repetitious and overly formal effect, though he did admit there were ways to mitigate the monotony.

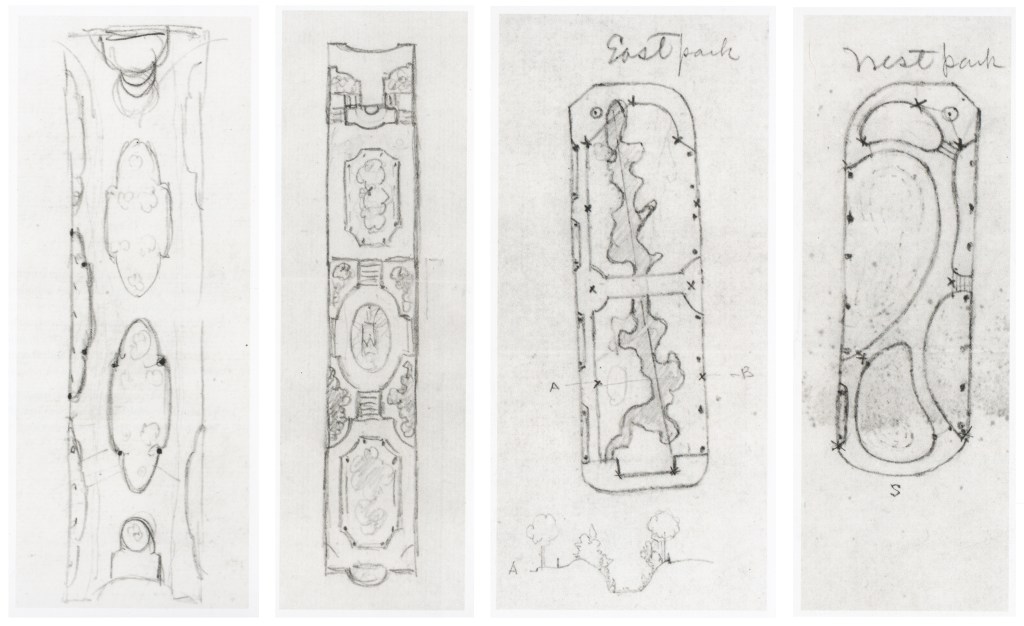

Left to Right: North (Winter); South (Spring); East (Summer); West (Fall)

As a counter to the commissioners plan, Olmsted suggested that each of four parks should have their own unique plan, arguing that from within, the parks do not relate to each other, but rather to the monument. Olmsted suggested that there should be:

“a distinct line of masonry, then, in looking toward the monument from within the grounds, it would seem to stand, as in fact it does, upon a broad, level, central plateau or terrace. The grounds would then appear much more distinctly detached and would be more readily regarded as apart from the monument and their treatment might me much more complex in its interior detail without incongruity and without serious effect to the monument.”

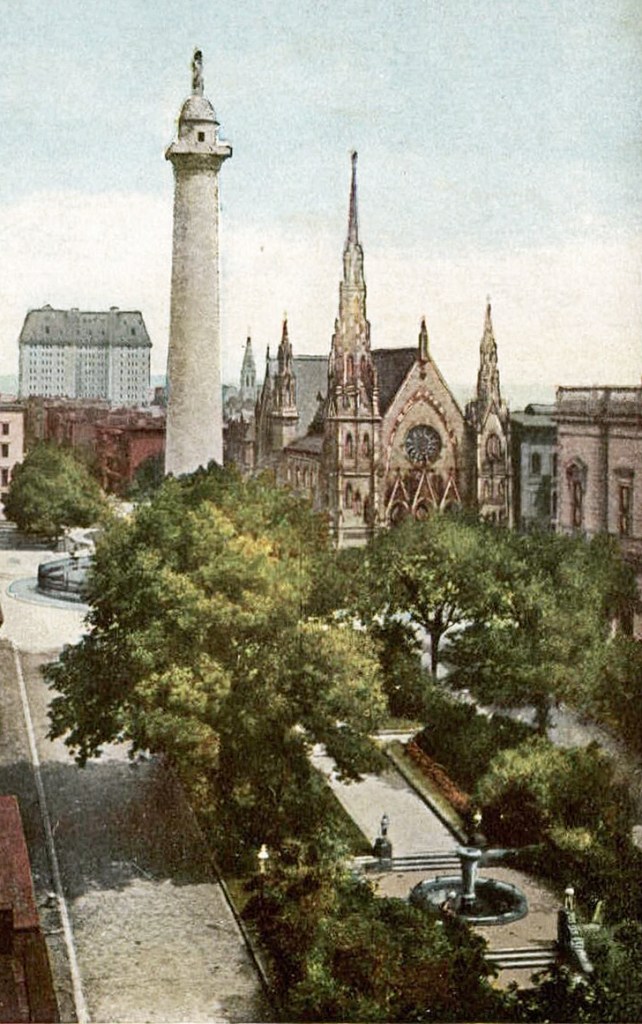

The brilliance in Olmsted’s idea was that the four parks could be better integrated into the surrounding neighborhood while maintaining a focus toward the monument. To increase each parks’ relationship to its surroundings, Olmsted eliminated the perimeter walls and fences in favor of low, granite edging while aligning the entrances and crosswalks to some buildings around the parks like the Peabody Institute and the Mount Vernon Square Methodist Church.

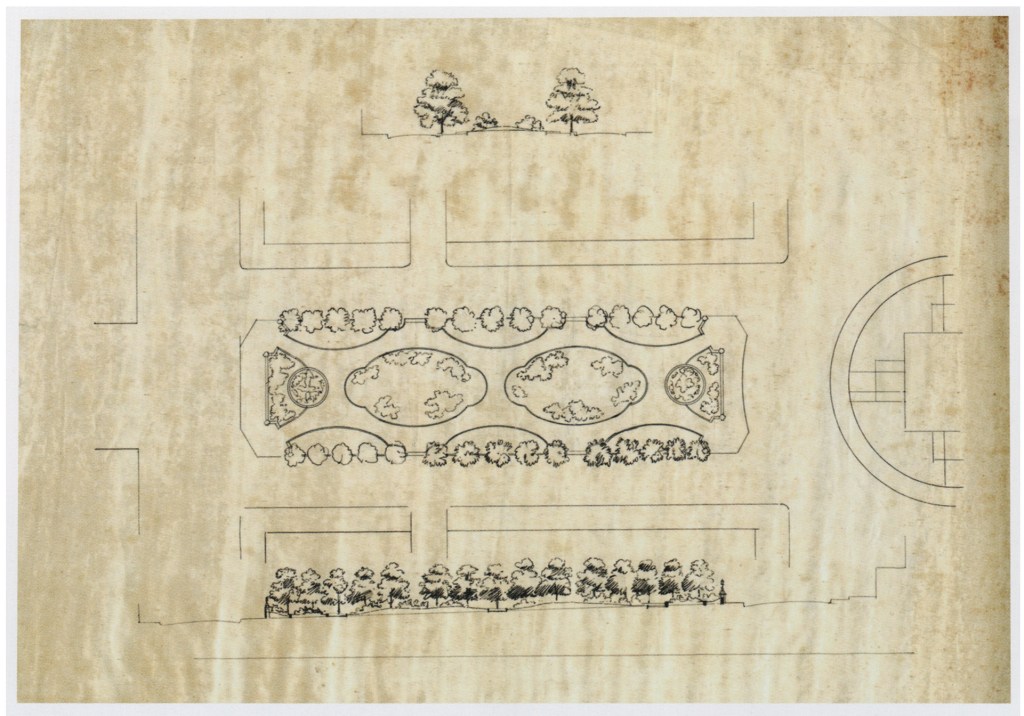

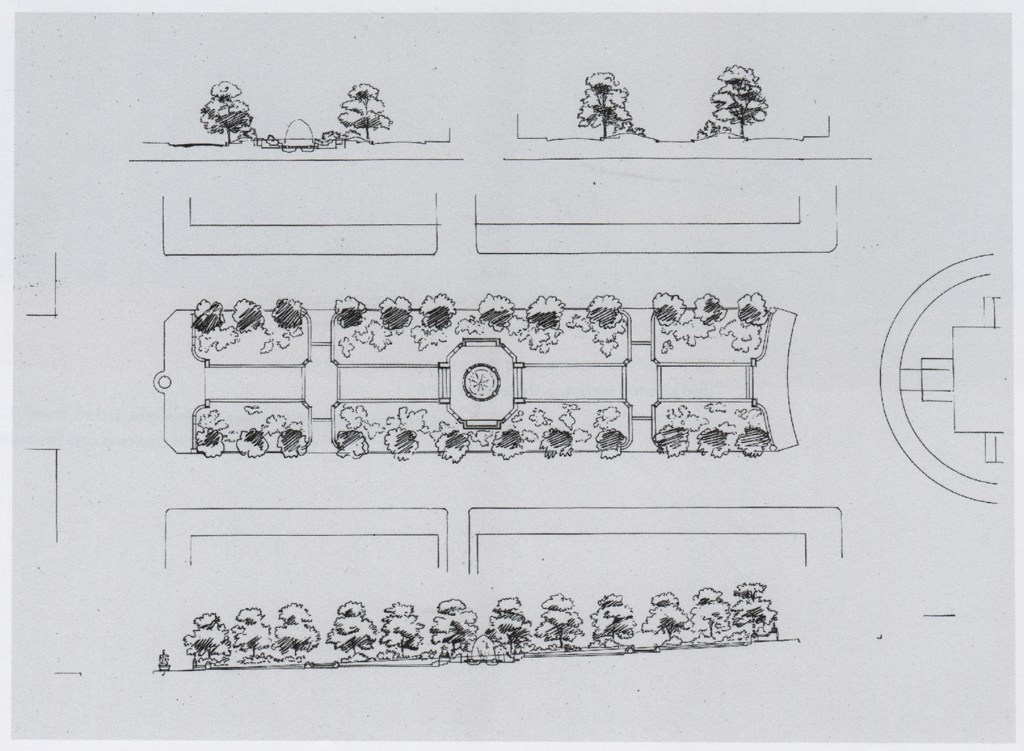

Since this allowed each park to be treated individually, Olmsted then created a scheme for planting a flora-cycle based on the four seasons, allowing for each park to be highlighted at different times of the year. Each would then have a fountain decorated to reflect it respected season. For example, the “Winter” or north park would be primarily planted with evergreens with a fountain designed using larger rocks and boulders. The “Summer” or east park would have a cooling grotto with a sunken garden and shaded walks (this soon evolved into the concept for the design of the Summer-house in Washington, D.C.). The “Autumn” or west park would have a harvest theme and planted with bright flowers. The “Spring” or south park would be the most formal, with a stepped terraces and a central fountain spraying into the air and plantings which bloomed early in the year. The space was to be divided into four distinct zones, each set within its own terrace. At the end facing the monument was to be a wall fountain and basin with steps on either side. Two of the terraces were designed with central flower beds (casually alluding to his design for the North park). The centerpiece of the design was to be a fountain set in an oval basin with planting at each corner of the terrace. Olmsted’s estimate to renovate the four parks was $50,000.

After Olmsted presented this initial scheme, the commissioners decided to to have Olmsted complete the North and South parks, opting for a less expensive alternatives to the east and west parks. For the North park, Olmsted basically refined his original scheme of oval and half-oval lawns constructed as small mounds with trees lining the streets along the sides. Apparently, Olmsted had originally intended for fountains at either end but that idea was never implemented and circular flower beds were constructed in their place.

At each end of the park, Thomas Wisedell designed the corner entrances with dwarf walls connected by a wrought iron fence and short piers topped with wrought iron gas lamps, sort of a miniature and simplified version of some of the stonework that he designed for the Capitol Grounds at Washington, D.C.

Bottom: Stonework at the Capitol Grounds, Washington, D.C.

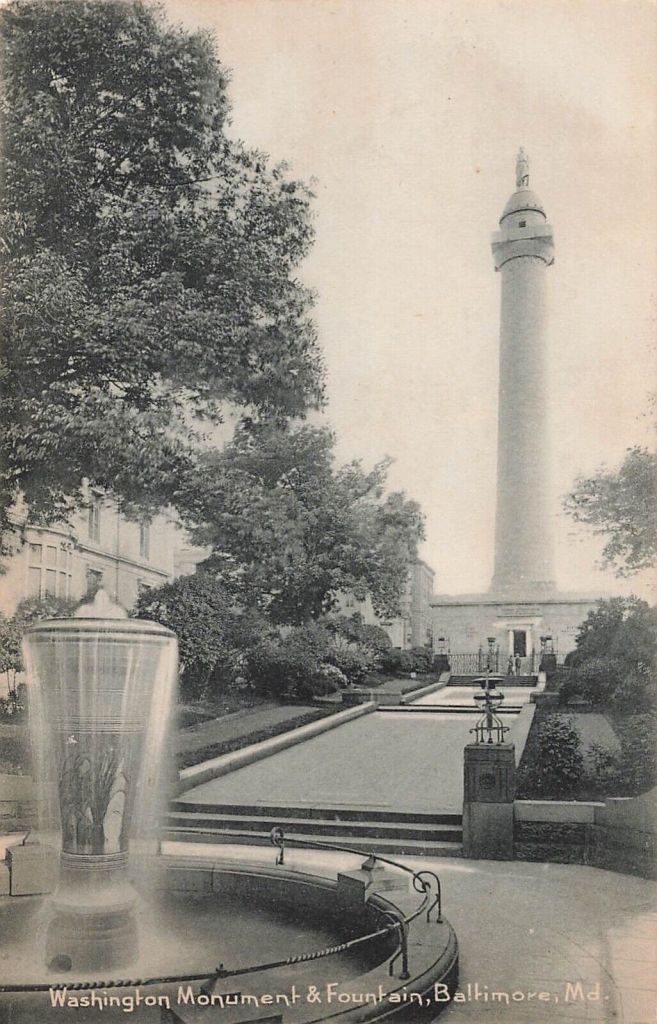

Since the South park at Mount Vernon Square also served as the primary approach to the Washington Monument, this was considered to be the most important of the four parks and Olmsted planned it accordingly. Olmsted’s original plan avoided a central axis by treating the space as connected terraces. Perhaps because of the South park’s role as the principle approach to the monument, his final design emphasized a central axis connecting a series a terraces, the smallest of which served as crosswalks through the park. Flowers and shrubs and lawns were placed closer to the walks while taller trees lined the two sides along the street. In the middle of the park was a fountain set in a circular basin and centered within an octagonal terrace.

Like the North park, Thomas Wisedell designed short, dwarf walls with simple granite piers and wrought iron gas lamps. The centerpiece, however, was the granite fountain set in a circular base. This was designed in the shape of a tulip vase with a small center jet spraying water upwards while water cascaded over the rim. The fountain itself was had incised lines above and below sculptural figures of cranes and reeds, showing Wisedell’s burgeoning interest in Japanese design — an idea discussed with the fountain erected on the western Capitol grounds in Washington, D.C. (Part 4f).

Besides the architectural features found in the North and South parks, Olmsted also had Thomas Wisedell design a circular path which was paved with granite blocks which were dyed red, yellow and blue to match the colors of the Maryland state flag.

Olmsted’s final plans were created between January and April 1877. The existing iron fencing surrounding the four parks was removed in May by John L. Brooks and George Conn and transported to Druid Hill to be re-erected along Hookstown Road (now Pennsylvania Ave. It is unknown whether that fencing was actually reused.) The firm of William A. Gault & Sons of Baltimore was hired as contractors for cutting and installing the bluestone which like other Olmsted projects, came from Malden, N.Y. Engineers John Bogart and Charles M. Harris, who were both working on Central Park at that time (as well as other projects for Olmsted), were tasked with supervising the project.

Thomas Wisedell traveled to Baltimore in early June to stake out the grounds for the North and South parks. Wisedell had probably completed the plans for the stonework at the North park sometime in May 1877. Because that park did not need terraces or elaborate planning, it was the first to be completed. For the South park, however, it required complex grading and terracing as well as installing the pipes for the central fountain. As the North park was being completed in August and September, Thomas Wisedell was busy designing fountain and basin for the South park (This fountain may have been design simultaneously with the fountain at the western grounds of the Capitol in Washington, D.C.) Work on the South park was probably completed in October or November.

Though Olmsted was not responsible for remodeling the other parks at Mount Vernon square, when architects Robert Garrett and William Walters remodeled the West park in 1884, they clearly followed Olmsted’s original plan. This was, however a less expensive alternative. When compared to the mounded beds, tree-lined streets and custom stonework of the North Park, we can get a sense of the richness of color and texture that Olmsted would have implemented.

As for the East park, it is unknown if the same architects were responsible, though many of the design features echo those found on the West park. The design for the East park did not seem to borrow from Olmsted’s original scheme, though its overall design did relate to the West park.

When Olmsted wrote of his ideas for redesigning the parks at Mount Vernon Square in December 1876, he expressed his intentions to create a design that reflected the simplicity, grandeur and permanence of the Washington Monument. With that said, the monument proved to be the only thing the city regarded as permanent. Beginning in 1909, the City of Baltimore had begun working with Thomas Hastings of the well-known New York architectural firm of Carrere & Hastings to create a new plan for the city. In 1916, that new plan began to incorporate new ideas for Mount Vernon Square. All four parks were soon redesigned under the precepts of the City Beautiful Movement, basically erasing Olmsted’s vision along with Thomas Wisedell’s intimately scaled designs in favor of an almost baroque monumentality.

Further Reading:

- https://enclosuretakerefuge.com/tag/carrere-and-hastings/

- https://mountvernonplace.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Humphries-Carrere-and-Hastings-in-Baltimore.pdf

- https://crowd.loc.gov/campaigns/olmsted/subject-file/mss351210250/mss351210250-1/

- Beveridge, Charles E., Meier, Lauren and Mills, Irene, editors, Frederick Law Olmsted: Plans and Views of Public Parks (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015)

- Journal of the Proceedings of the First Branch City Council of Baltimore, at the Sessions of 1875-1876 (Baltimore: Printed by John Cox, 1876).

- Journal of the Proceedings of the First Branch City Council of Baltimore, at the Sessions of 1876-1877 (Baltimore: Printed by King Bros., 1877).

- Journal of the Proceedings of the Second Branch City Council of Baltimore, at the Sessions of 1875-1876 (Baltimore: Printed by John Cox, 1876).

- The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted. Volume VII: Parks, Politics and Patronage 1874-1882 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).

- “Washington Monument Surroundings,” The Baltimore Sun (June 8, 1877): p. 4.

- “Washington Monument Adornments,” The Baltimore Sun (Aug. 11, 1877): p. 4.