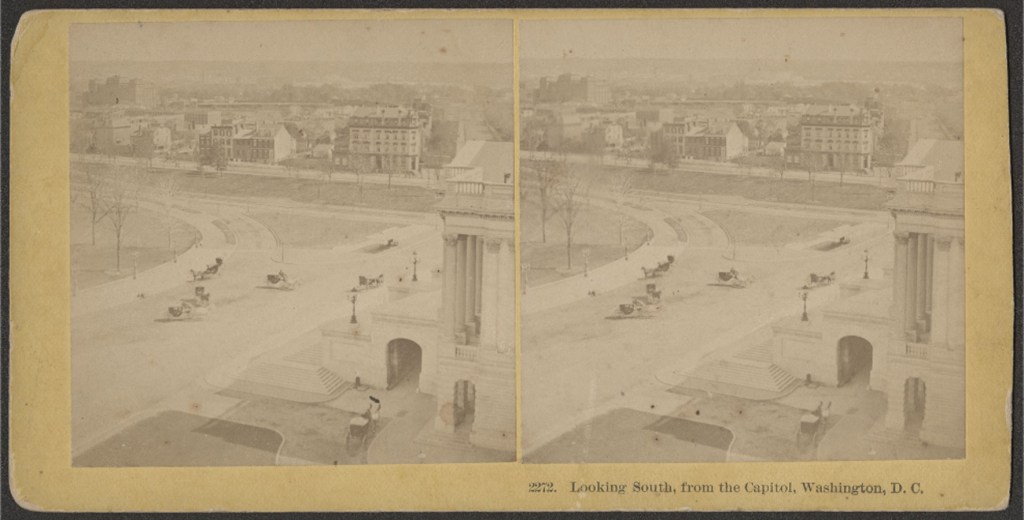

When Frederick Law Olmsted created his plan for the East Plaza on the Capitol grounds in 1874, he included an ornamental, iron shelter next to the unbuilt flagpole (see previous post) near the New Jersey Avenue entrance. This was intended to be used by the Georgetown & Washington Railway who had recently announced that they were extending their horse-drawn trolley from the B&O railroad station along the west and south sides of the Capitol grounds and on to the Navy Yard.

Though only one shelter appeared on Olmsted’s 1874 plan, a second, identical shelter was erected at the same time on the north side of the grounds near the Delaware avenue entrance beside that intended flagpole as well (marked A on the map). This was to serve the horse-drawn street cars operated by the Metropolitan Railway.

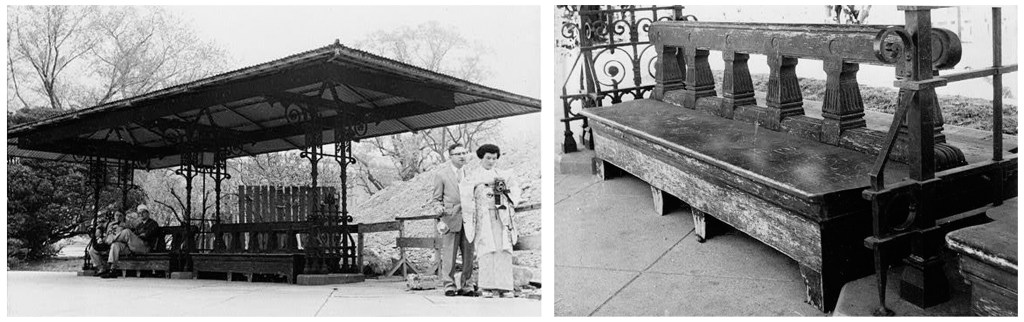

The shelters were constructed principally of wrought iron (with a few cast iron pieces) which were bolted together to form the ornamented columns. The girders, beams, rafters and ridge were all constructed from rolled steel which supported a wooden roof. At night, the shelters were lit by three gas lanterns which were centered at the top of each of the paired columns. The twisted columns and curled ends, gave a sense of nature being stylized in a way that was already common in English and European designs reflecting the early Arts and Crafts Aesthetic Movements. Like other features designed for the East Plaza, Wisedell combined Indo-Islamic influences with the the naturalistic designs of Christopher Dresser giving a stylized interpretation of vines growing upwards.

According to Olmsted’s report of September 1875, the architectural features on the East Plaza which had been designed by Thomas Wisedell were mostly completed and the “ornamental shelters at the termini of the car tracks are in the course of construction.” The Watson Manufacturing of Patterson, New Jersey (a firm already famous for its railroad bridges) was hired to create the various iron and steel components. Apparently, there were problems with the longer angle iron pieces along the cornice which kept the shelters from being fully completed until June or July 1876. According to the report filed on November 1, 1876, the total cost of both waiting stations was $1970.00.

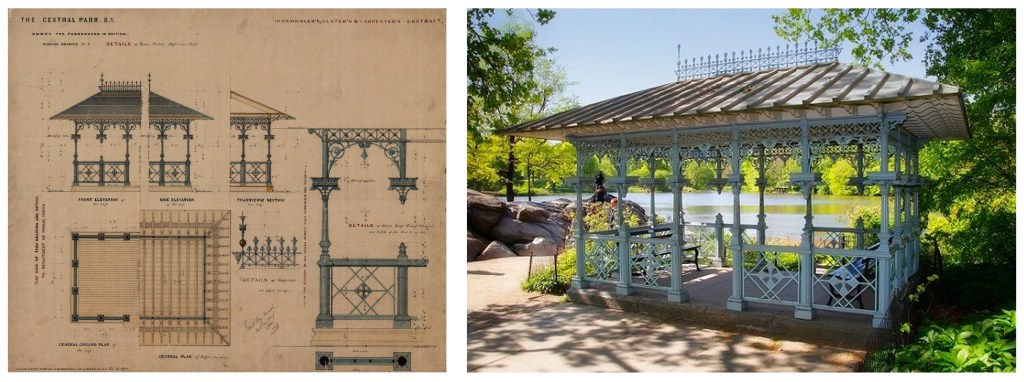

The idea of placing streetcar waiting stations at two of the principle entrances was not unique to the Capitol grounds. In 1871, Jacob Wrey Mould had designed an iron station for the southwest corner of Central Park in New York City. Like the stations at Washington, this too was principally constructed of cast and wrought iron components and presents a visual contrast between the designs influences of Mould and Wisedell. While Mould’s design combined early Christian and Gothic details from Northern Italy, Wisedell chose to principally rely on the designs ideas of Christopher Dresser by abstracting nature while portraying plant growth.

Waiting station shown in background.

To complement the waiting stations, Thomas Wisedell was asked to design seated trellises which will be the subject of the next post.

Further Reading:

- https://crowd.loc.gov/campaigns/olmsted/subject-file/mss351210416/mss351210416-43/

- “Improvements at the Capitol Grounds,” The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), Nov. 15, 1875, p. 1.

- The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted. Volume VII: Parks, Politics and Patronage 1874-1882 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).

- Brown, Glenn, History of the United States Capitol vols. I and II (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1900, 1903).

- Dresser, Christopher, The Art of Decorative Design (London: Day & Son, 1862).

- Keim, DeBenneville Randolph, Keim’s Illustrated Handbook. Washington and Its Environs: A Descriptive and Historical Hand-Book to the Capitol of the United States of America. 6th ed. (Washington, D.C.: DeB. Randolph Keim, Publisher, 1875).

- Weeks, Christopher, AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C., 3rd ed. (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994).