Since writing about the fountain back in May, new information has come to light which changes the timeline of how the western part of the Capitol grounds had developed. It was previously thought that the fountain was one of the last architectural features to erected, it is now known that that was actually the first. With this information in mind, much of the post on the fountain has been rewritten.

When Frederick Law Olmsted and Thomas Wisedell had created the plan for the Capitol Grounds in the summer of 1874, they had only included architectural features for the East Plaza as well as the Capitol terrace. Though the western grounds had been planned, no architectural elements had been included. Olmsted soon formulated his ideas and throughout 1875 and early 1876, Thomas Wisedell designed not only the fountain, but also the stone walls and piers that would form the principle entrances at Pennsylvania and Maryland Avenues (see Part 4e).

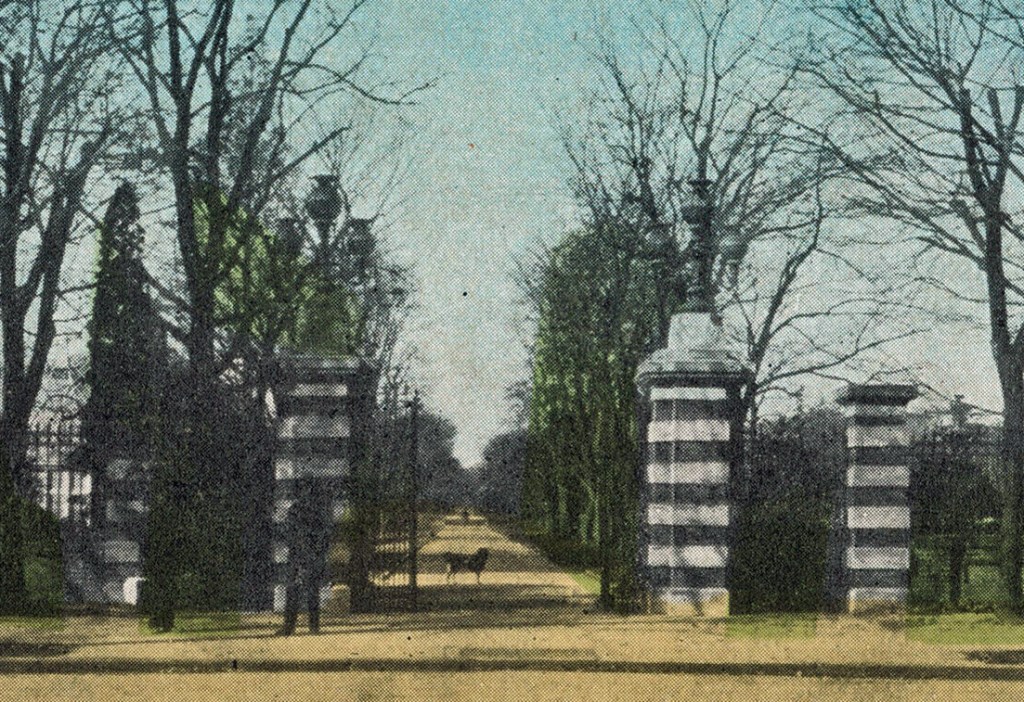

When the Capitol grounds were laid out in the late 1820’s, Charles Bullfinch had designed a perimeter wall along the western boundary with two gatehouse at the central entrance and gate piers at Pennsylvania and Maryland Avenues. When Olmsted re-planned the grounds in 1874, he retained the perimeter walls but eliminated the central walk and had the gate houses and piers relocated to other parts of the city. In place of the gatehouses and former entrance, Thomas Wisedell added new walls, creating an alcove for the newly designed fountain.

Bottom: Old wall to the left and new wall at center and right.

Richard Rothwell & Co. was hired as the contractor in 1876 with a bid of $12,614.74 which included the fountain and it new alcove as well as all of the stonework at the Pennsylvania and Maryland Avenue entrances. By the end of 1877, the fountain and the walls forming its alcove had been erected with the Pennsylvania Avenue entrance being completed the following summer. Due to budget restrictions, the Maryland Avenue entrance was not completed until 1881, at which time all of the bronze lanterns were also completed.

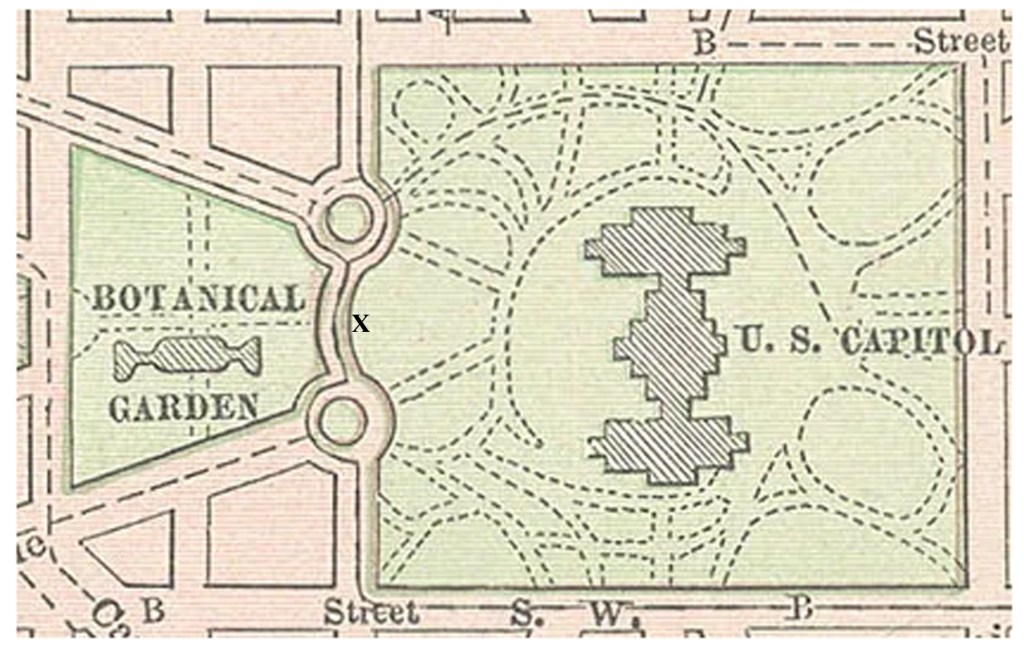

Like the former entrance, the fountain was centered not only on the Capitol building, but also on the entrance to the United States Botanical Garden. The garden had been located just west of the Capitol grounds since 1842 with its entrance piers along First Avenue having been constructed in the 1850’s. What this implies is that the fountain’s design was not solely intended for the Capitol Grounds, but also as a focal point relating to the Botanical Gardens.

It is this later point that is of interest since it helps explain why the fountain exhibits a different style than the rest of the decorative stonework Wisedell designed for the Capitol grounds. The forms and motifs found the stonework at the Pennsylvania and Maryland Avenue entrances (see part 4e) relate directly to the stonework Wisedell designed in the early 1870’s for the Concert Grove at Prospect Park in Brooklyn, NY.

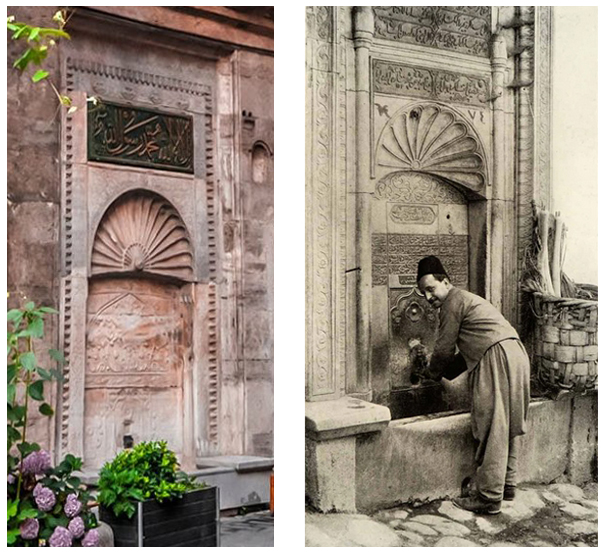

Similar to earlier works in Central Park and Prospect Park by Jacob Wrey Mould and Calvert Vaux, the inspiration for the fountain traced its roots to Islamic and Ottoman architecture. Its overall design echoed the drinking fountains with wash basins (sebilli) found throughout Turkey. Rather than inscriptions from the Koran, however, Wisedell ornamented the flat panels with stylized plants.

Right: Image of Ahmediye Cesmesi (fountain), Istanbul, from The Turkish People by Lucy Garnett, 1909. The fountain dates 1721-22.

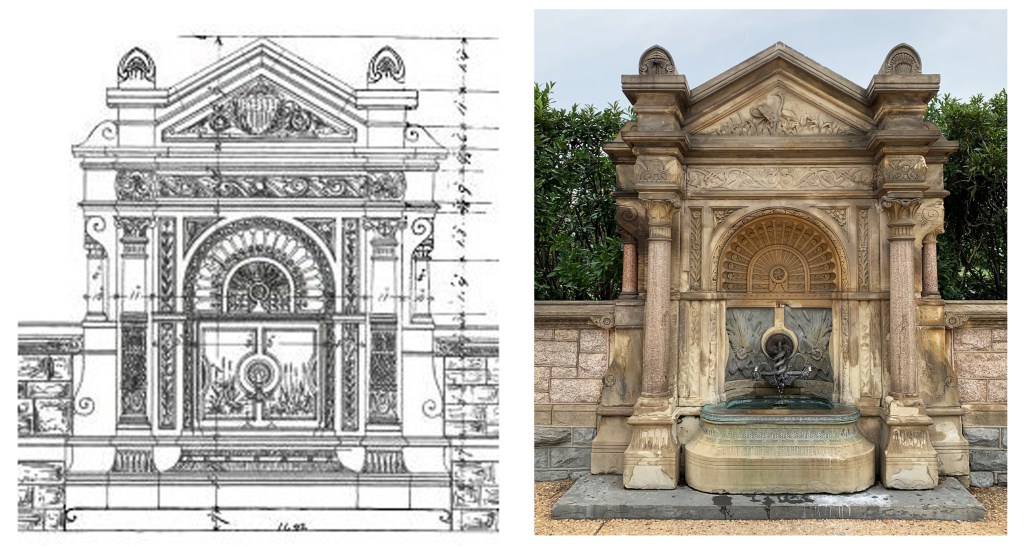

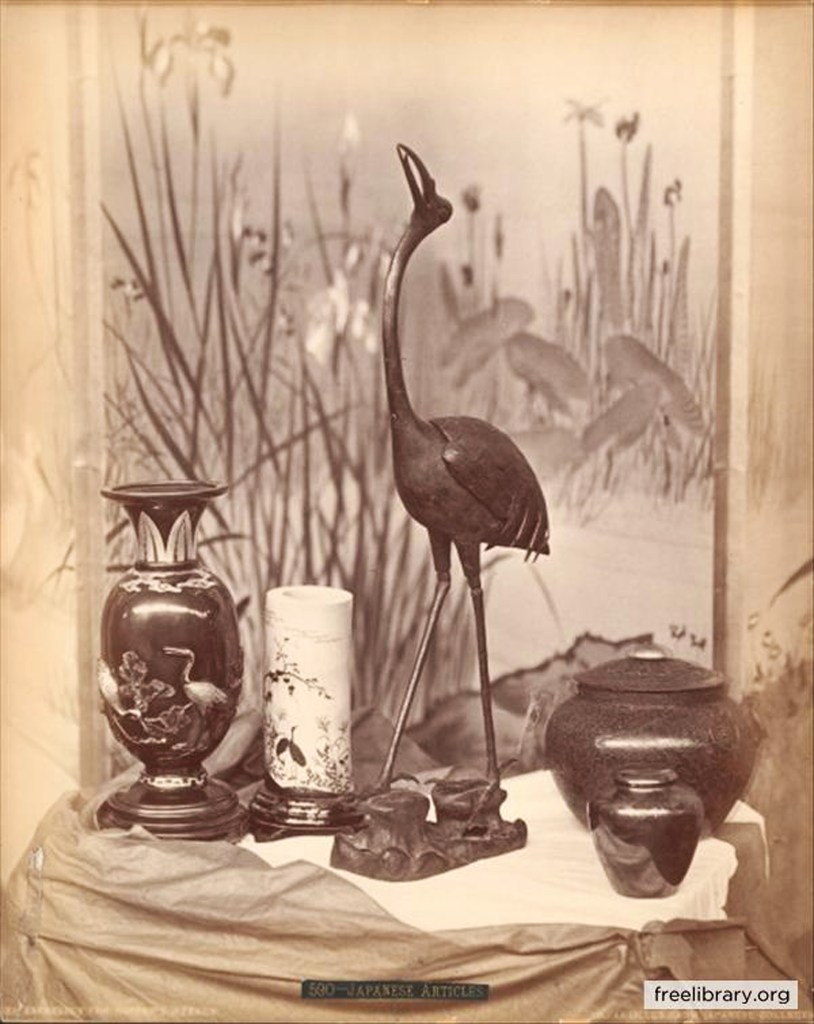

A comparison of the original design for the fountain by Thomas Wisedell from around 1875 shows this transition in tastes that followed the Centennial Exposition. The drawing on the right shows Wisedell incorporating renaissance, gothic and Indo-Islamic, Ottoman and Native American details mixed with botanical designs inspired by the early writings of Christopher Dresser. The pediment was then designed with flowing ribbons and a flag shield with thirteen stripes with stars above. It is here that were find the most radical change with the shield being replaced by a picturesque scene from a Japanese marshland. Below, the frieze was redesigned into a simpler and flatter vine motif it a style more characteristic of the then nascent style that would evolve into the later Arte-Nouveau movement. Even the largest columns were simplified having their decorative features abandoned for simple, polished granite.

By late 1876, Wisedell began incorporating contemporary ideas reflecting Japanese influences characteristic of the Aesthetic Movement in Britain and showed a broader eclecticism that was less reliant of the influences of Robert Jewell Withers, Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould as well as the early designs of Christopher Dresser. Following the London International Exhibition (1862)and the Exposition Universelle in Paris (1867), Japanese influences began appearing in England and France. By the late 1860’s and early 1870’s companies like Liberties of London and Tiffany & Co. of New York began importing enamelware and ceramics while designers like Edwin Godwin and Walter Crane were incorporating Japanese styles, forms and patterns into their furniture and tiles, respectively.

Although vestiges of the Aesthetic Movement were found in the United States following the 1867 exposition in Paris, it was not until after the Centennial Exposition of 1876 in Philadelphia that Japanese influences would be felt in every aspect of American architecture and design. A major catalyst for that change in taste came through Christopher Dresser. In 1876, the British government appointed Dresser as a cultural emissary to Japan. En route to Asia, Dresser stopped to visit the Centennial Exposition and present a series of lectures at the Philadelphia Museum and School of Industrial Art. Prior to his visit to Philadelphia, Edward C. Moore, the head of the design studios for Tiffany & Co., had commissioned Dresser to purchase over a thousand objects of Japanese design to be sold in their New York showroom.

Whether Thomas Wisedell had seen any of Dresser’s Philadelphia lectures is unknown, though Wisedell was working in Philadelphia designing the new gate-lodge and other improvements to the Schuykill Arsenal in 1876 (the subject of a future post). How Thomas Wisedell became influenced by Japanese design is still a matter of conjecture, but what is known is that following the Centennial Exposition, he began incorporating Japanese motifs, and in regards to the fountain, it is these Japanese features that tie the fountain to the Botanical Gardens.

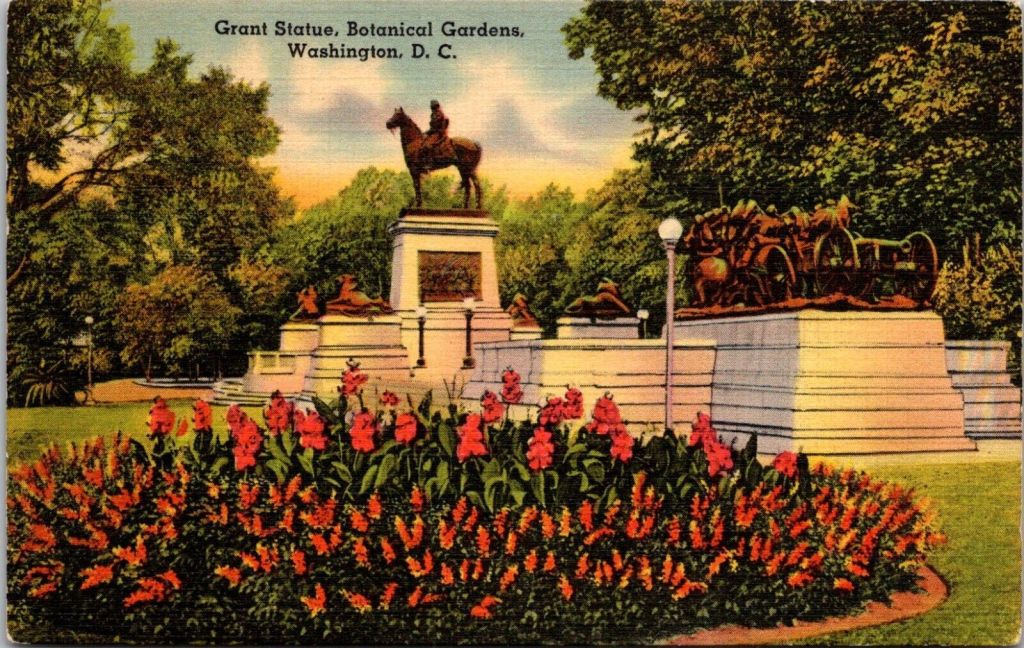

Over time, the relationship between the fountain and the Botanical Gardens has been lost. Following the re-planning of the federal city under the McMillan Commission of 1901, the size of the mall was extended and competitions were held to erect a monuments to both General Ulysses S. Grant and Abraham Lincoln. The Grant monument was erected at the east end of the mall just inside the Botanic Gardens between 1906 and 1922. At the same time that monument was being erected, the Lincoln Memorial was being constructed at the west end of the mall and also completed in 1922, intentionally book-ending the National Mall with monuments to the two men the nation had credited with winning the Civil War and preserving the union of the states.

In 1933, the Botanical Gardens were officially removed to a new location and its grounds were turned into a massive reflecting pool. The scale and orientation of the Grant Monument had completely altered the context of where and why and fountain had been constructed. Since the use and scale that had dominated Washington, D.C. prior to 1901 had been completely altered out of existence, the fountain now sits as a strange curiosity with little context to give it meaning, appearing as a relic of a bygone era sandwiched between the great dome of the U.S. Capital Building and the National Mall.

Along with the Concert Grove in Prospect Park, the work that Thomas Wisedell accomplished in Washington, D.C. represents his greatest contributions to the history of parks in the United States. All park structured he designed in Buffalo, Baltimore and Montreal (which will be subjects of later posts) were either left unrealized or have fallen victim to changing tastes and often replaced by less inventive structures leaving the works in Washington and Brooklyn as important survivors.

Since the work that Wisedell did in Washington, D.C. spanned from 1874 until his death in 1884, there were numerous other projects that also happened during that decade. What appears to be the next commissions for residential work on Long Long Island. However, the the sake of a cohesive narrative, this blog will continue with Wisedell’s work ornamenting other parks and grounds for public buildings before exploring his residential work.

With that said, In the spring of 1875, as Thomas Wisedell was completing plans for the walls, lamps and fountains on the East Plaza of the Capitol ground in Washington, D.C., Frederick Law Olmsted was offered the commission to improve the grounds at the Schuylkill Arsenal in Philadelphia, bringing Thomas Wisedell along to design architectural features for the Quarter-master’s house and redesign the entrances with new Gatehouses and lodges.

Further Reading:

- https://crowd.loc.gov/campaigns/olmsted/subject-file/mss351210420/mss351210420-60/

- https://chrs.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/24on9thStNEownersHouseHistory2020.pdf

- Allen, William C., History of the United States Capitol: a Chronicle of Design, Construction and Politics (Washington, D.C.: The Government Printing Office, 2001).

- Annual Reports of the Architect of the United States Capitol (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1878-1883).

- Documentary History of the Construction and Development of the United Stated Capitol Building and Grounds (Washington, D.C.: The Government Printing Office, 1904).

- Garnett, Lucy M. J., The Turkish People: Their Social Life, Religious Beliefs and Institutions and Domestic Life (London: Methune & Co., 1909). This book was also published in the United States as Home Life in Turkey (New York: The MacMillanCompany, 1909).

- The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted. Volume VII: Parks, Politics and Patronage 1874-1882 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).

- The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted. Volume VIII: The Early Boston Years 1882-1890 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013).

- Brown, Glenn, History of the United States Capitol vols. I and II (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1900, 1903).

- Weeks, Christopher, AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C., 3rd ed. (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994).