In February 1876, Francis Kimball was asked to submit plans to design new facilities for the Hartford Orphan Asylum. For this commission, Kimball would once again compete against his friend and rival George Keller.

The Hartford Orphan Asylum was established in 183l and formally incorporated two years later. Its mission was to care for orphaned boys and intended as a counterpart to the Hartford Female Beneficent Society (founded 1809) which had cared for “needy, indigent females” by placing them with various families in Hartford. The boys in the care of the asylum were also placed with various families until 1836 when a former boys’ school on Washington Street was purchased and renovated to care for the orphaned boys.

In 1857, David Watkinson (1778-1857), who had been a founder and past president of the orphan asylum, had willed $20,000 in order that the two charities would be combined and a new building would be constructed to house the institution.

The two institutions were formally united in 1865 under the Hartford Orphan Asylum and both boys and girls were cared for in the building on Washington Street. This union, along with the increase in orphans following the Civil War, forced the trustees to consider either constructing larger facilities or making substantial additions and upgrades to their current building.

In 1866, fund-raising began in earnest, though nothing concrete was planned. That year seven of Hartford’s wealthiest citizens (including James Goodwin) pledged a total of $35,000 towards the erection of a new building. Over the next few years, various architects and builders had informally offered plans but were deemed unsatisfactory or far too expensive at the time.

It was not until 1874 when James Goodwin and George Bartholomew purchased fourteen acres of land known as the “Penfield Farm” on Putnam Street, donating it as the future site of the asylum. This tract was sought after it had been rejected as the new site for Trinity College, and was seen as quite optimal since it was located on a hill which offered proper drainage, a nearby river offering fresh water and was close to the countryside — assets lacking at their existing Washington Street facility.

The Washington Street building soon proved too small and at a very well attended public meeting on February 7, 1876, a plea was made for donations so that an architect could be hired, securing plans for the future of the institution. By this time, the need for a larger facility had become quite critical. Not only were children being denied admission, but some of the wealthier citizens had also lost faith in the organization, opting to send their contributions to other charities.

The following month, competing plans were offered by George Keller and Francis Kimball. Besides the new state capitol building, this would be the largest public building constructed in Hartford in the 1870’s and would have been highly coveted by either architect. Previously, Kimball had lost the Temple Beth-Israel commission to Keller but this time Kimball prevailed and on April 25, 1876 he was announced as the architect for the new orphan asylum.

It would not be a stretch to believe that James Goodwin and his wife Mary played a defining role in choosing Kimball as the architect. Kimball had known the couple since moving to Hartford in 1868. Goodwin was the president of Connecticut Mutual building for whom Kimball had helped design their new building in 1868 (see Part 12). James Goodwin was also a trustee for Trinity College and played a key role in appointing Kimball as the supervising architect for the college. Also, when Kimball and his wife traveled to London in December 1873, they were accompanied by the Goodwin’s youngest son Francis and his wife Mary. As for the asylum, James was the head of the building committee while his wife Mary was the asylum’s treasurer,

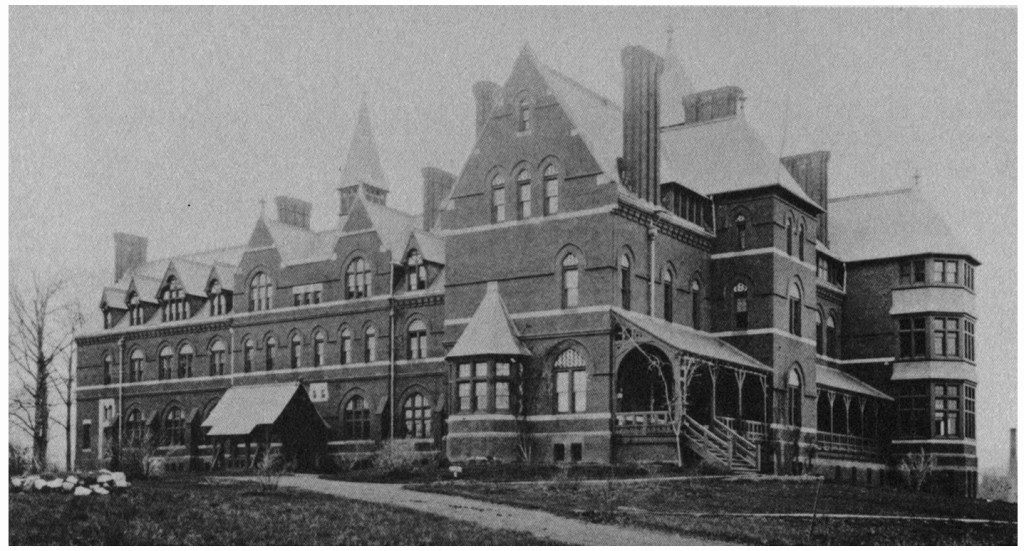

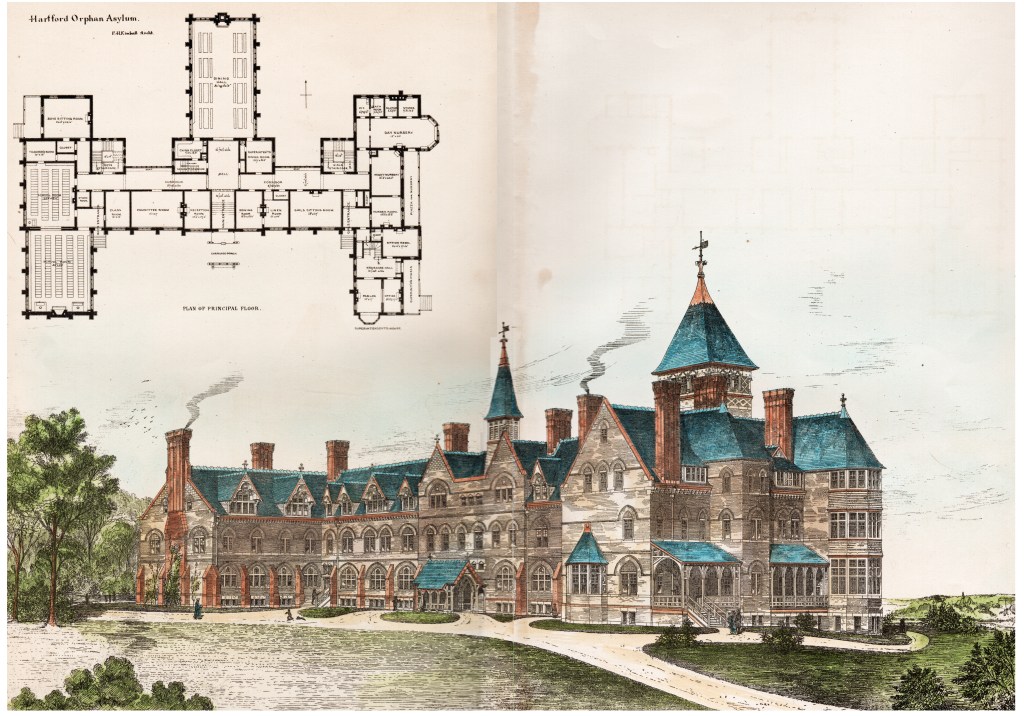

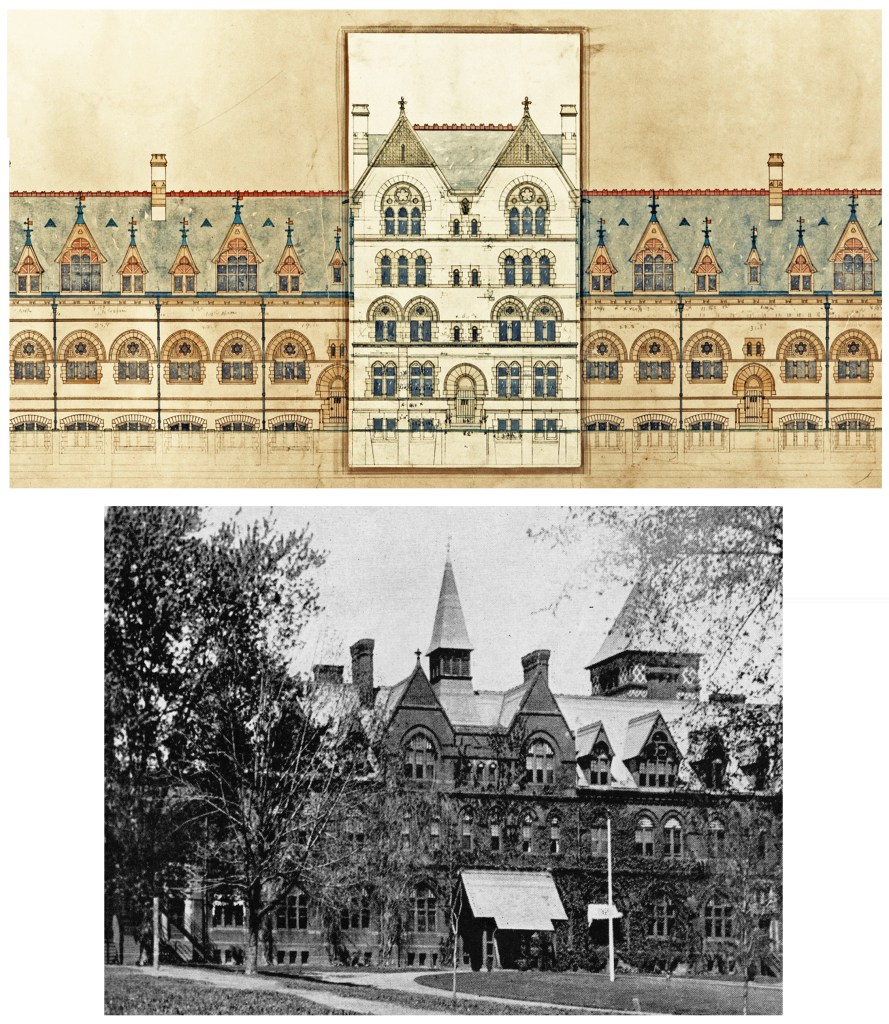

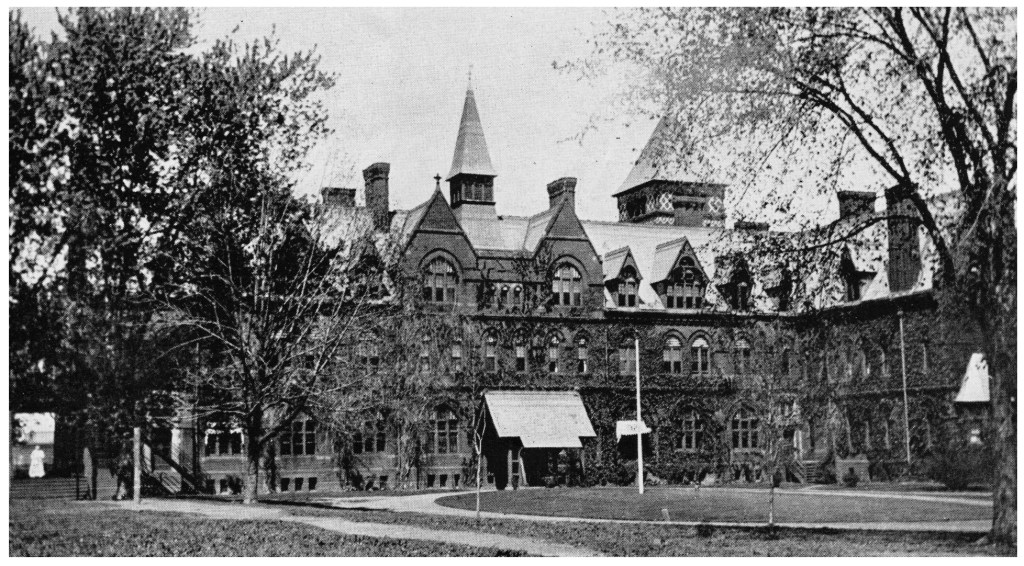

This project was remarkably complex since Kimball had to incorporate institutional, educational and domestic functions into a cohesive plan – a skill honed by his work with Trinity College. Kimball’s design was for a long, rambling, three story building of red brick trimmed with Portland brownstone and Ohio stone, providing contrasting tones and textures.

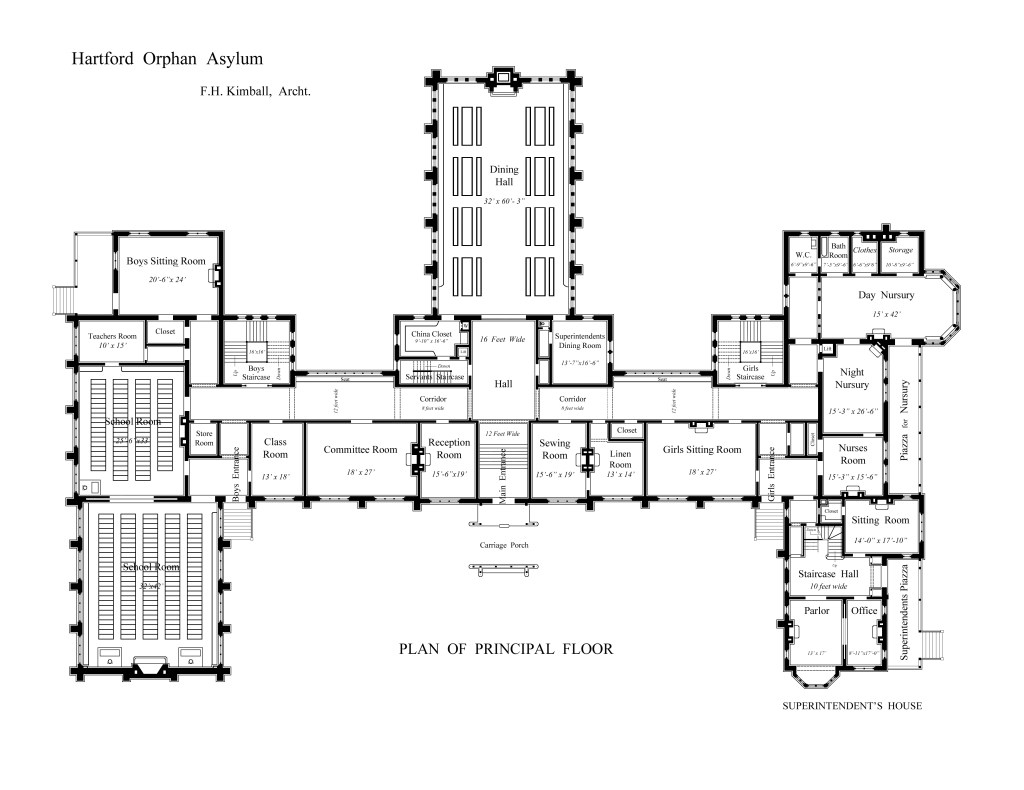

In true gothic revival fashion, the asylum’s exterior reflected its interior functions. This was designed with a central dormitory block with pavilions on each end. Perpendicular to and centered behind the dormitory was a large dining room. The dormitory was split in half, housing boys at one end and girls at the other. It was this separation that called for a broad corridor bisecting the building, necessitating the need to widen the central part of the dormitory block, splitting the gables and placing a ventilation tower in between.

Adjacent to the boys’ dorms was the school house wing to the west while the opposite wing to the east housed the superintendent’s quarters and the nursery. In the rear were stair towers set at the various intersections of the main block and the wings. The stair tower adjoining the superintendent’s wing was the tallest feature of the entire plan, creating an observatory over the city and countryside.

Right: Hampden County Courthouse, Springfield, MA, H. H. Richardson, arch., 1871-74.

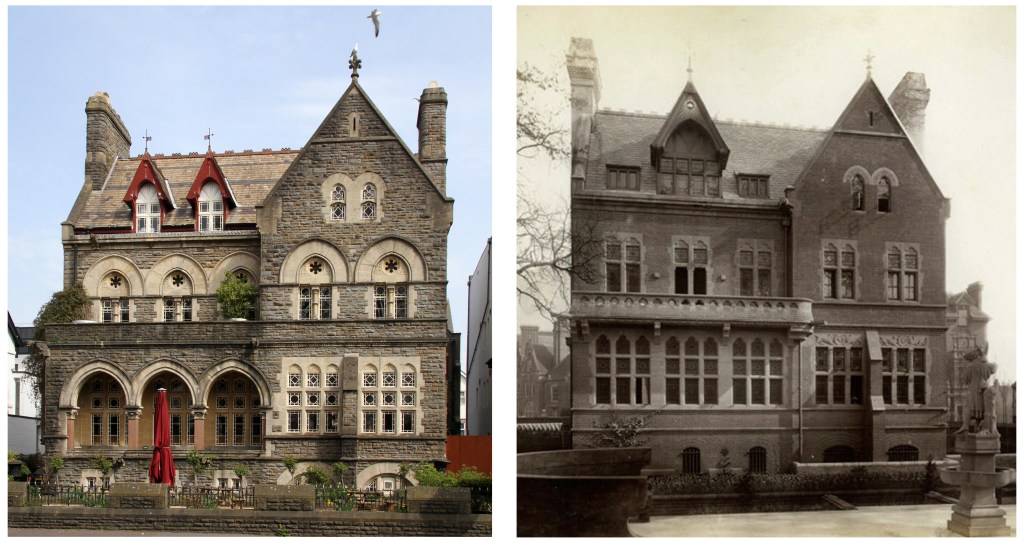

The larger fenestration along the ground floor as well as the complex massing, however, reveals a greater awareness of various architectural designs emanating from England. A simple comparison of Edward W. Godwin’s (1833-1886) Congleton Town Hall in Cheshire, England (1864-6) and H.H. Richardson’s Hampden County Courthouse (1871-74) in Springfield, Mass. clearly demonstrates that Kimball was much more reliant on British sources rather than American.

While working for Bryant & Rogers, Kimball had helped design the St. James Catholic Orphan Asylum for Boys in 1869, also in Hartford. That design was quite typical for orphanages with all the various needs placed within a single building with the children being housed together in a large rooms with multiple beds. With the Hartford Orphan Asylum, the children had smaller rooms shared with only one or two roommates. With this building, Hartford moved away from a traditionally planned orphanage into something that was more akin to a boarding school, and ultimately, that idea would underlie the entire project.

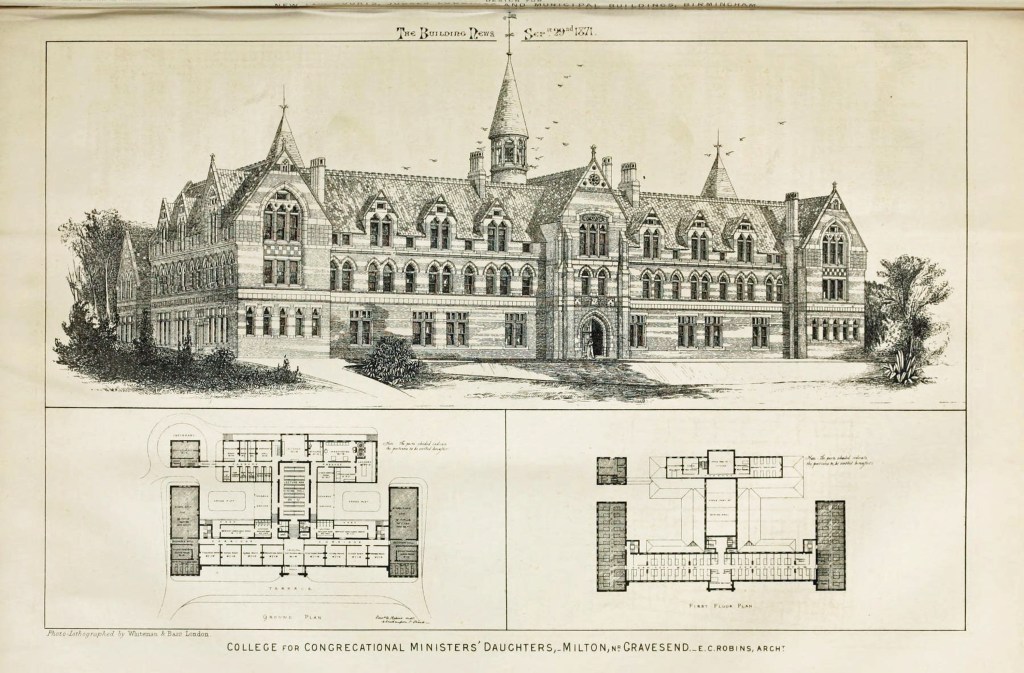

An examination of Milton Mount College, a boarding school in Gravesend, Kent, England designed by Edward C. Robins (1830-1918) and constructed 1871-73 demonstrates this idea. The ground floor was designed with a long central core which had school rooms and music rooms set in pavilion wings at each end. Centered at the rear of the building was a massive dining hall. The main part of the building had the Mistresses office, reception and smaller classrooms. At the corner of each wing was a square, stair tower with towers also set at the corners adjoining the dining room. On the upper floors were dormitories with rooms accommodating one, two and three students. Besides the building’s plan, Kimball also repeated the pattern of paired, Gothic windows along the dormitories.

Even if Kimball had not seen Milton Mount College while in England, it was quite well known at that time being published in Building News alongside the Alfred Langston’s Birmingham Town Hall which Kimball would have been introduced to while working for James Batterson in 1873. Also available was E. R. Robson’s book School Architecture which was published in 1874 while Kimball was in London. This book contained a lengthy description of the college along with elevations and plans.

Bottom: Hartford Orphan Asylum, ca. 1900.

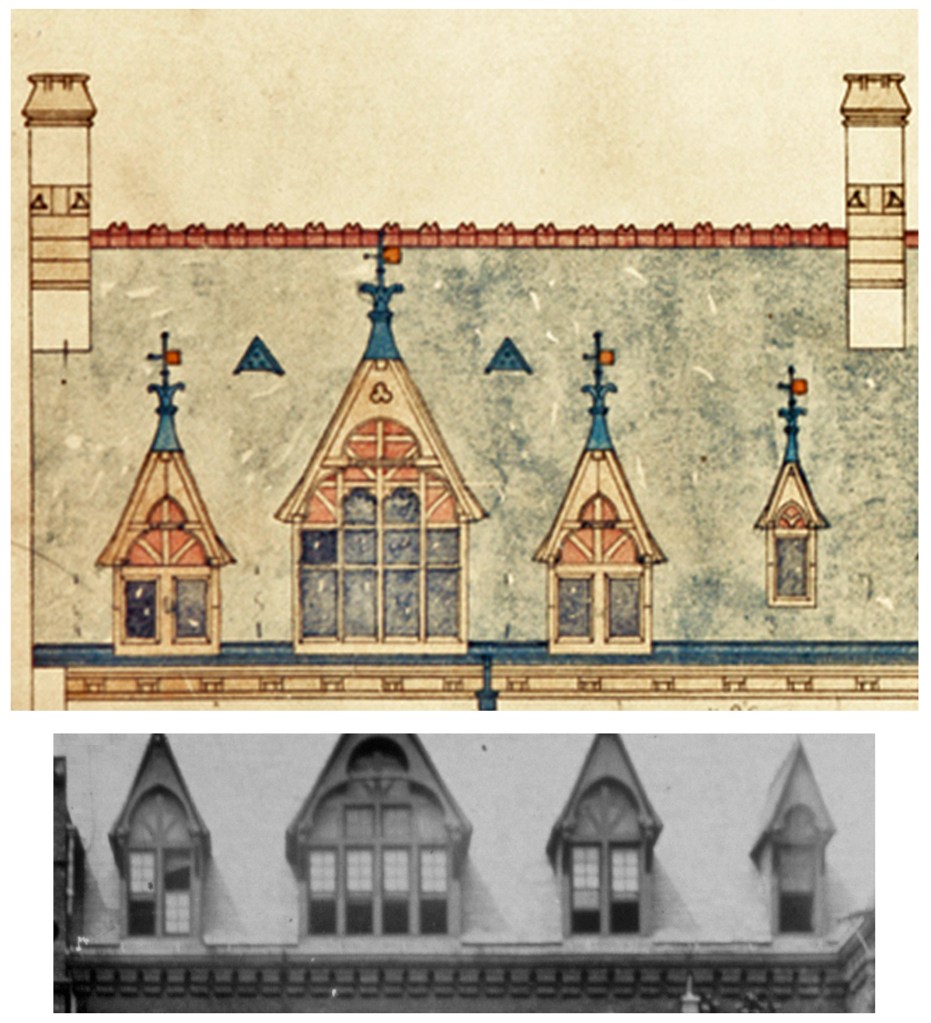

Though Kimball’s plans for the asylum echoed Milton Mount College, he also incorporated aspects of Burges’ plans for Trinity College, especially as seen in the basic massing of the dormitory block with its double-gabled tower flanked by ranges of dormitories. Kimball also incorporated the wooden dormers which had been designed for Seabury Hall in 1875.

Bottom: Dormers from the Hartford Orphan Asylum.

Besides Trinity College, the only wooden dormers known to have been designed by Burges were used in the McConnochie House (1871-74) in Cardiff, Whales, and Tower House, Burges’ own house on Medbury Road, London which was being designed in 1875 as Kimball was creating the final three-quad plan for Trinity College.

Right: Tower House (rear view), London, Eng., Wm. Burges, Arch., 1875-1881.

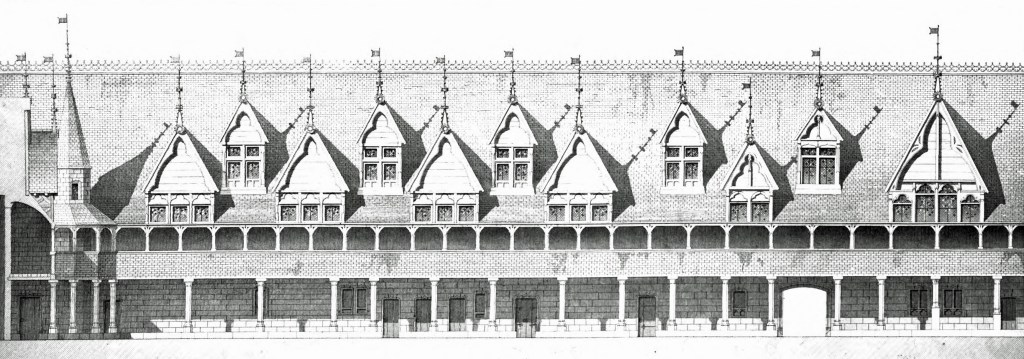

Wooden dormers began to appear in Burges’ repertoire in the early 1870’s but on a limited basis. Though Burges had designed wooden dormers for the unbuilt library at Trinity College, Kimball’s had expanded the idea with a design which seemed like an adaptation of those used on the Hotel-Dieu in Beaune, Burgundy, France; a hospital originally built in the mid-fifteenth century following the Hundred Years War.

Kimball would continue to quote contemporary British sources with the introduction of lighter, more delicate, domestic features on the nursery wing, especially the bay window on the side as well as the three story, projecting octagonal bay constructed almost entirely of transomed, sash windows. Here, Kimball seamlessly integrated features not only from Godwin, but also from W. Eden Nesfield (1835-88) and Richard Norman Shaw (1831-1912) demonstrating how the Gothic Revival and Queen Anne styles were quite compatible.

By the mid-1850’s, the Gothic Revival had progressed and architects, archeologists and academics were revisiting Romanesque and Gothic architecture of the past and Hotel Dieu (also known as the Hospices de Beaune) was highly regarded. Both Richard Norman Shaw and W. Eden Nesfield had sketched and published the building, especially the former who sketched a near perfect facsimile of the loggia and dormers.

Another source, however, may have been from Eugene-Emmanuel Viollet-Le-Duc’s Dictionaire Raisonne de L’Architecture Francaise. Kimball had purchased the entire ten-volume set at the publishing house of B. T. Batsford while he was in London in 1874. This was probably purchased on Burges’ recommendation since he was one of the earliest proponents the writings of Viollet-le-Duc. Burges was clearly more fascinated with Viollet-le-Duc’s illustrations, famously writing, “probably not one buyer in ten reads the text” and for Kimball, this just may have been the case.

While Kimball was in London, Viollet-le-Duc’s son in law, Maurice Ouradou (1822-1884) was in the process of restoring the chapel and Great Hall at the Hotel-Dieu at Beaune, Burgundy, France. It is unknown whether Kimball visited this well-known building, however, in the Dictionaire Raisonne, Viollet-Le-Duc wrote about the building in the section on hospital design. This lengthy description also included plans and a courtyard woodcut-illustration clearly exhibiting the Flemish dormers.

In each of those publications, the dormers were faithfully sketched showing that the dormers were open to the loggia below allowing for natural light the flood into the recessed doors and windows. When Kimball designed the dormers for Trinity College in 1875, there was no loggia so the dormers were designed with sash windows and set right along the eve.

As it turned out, there is a source illustration this specific treatment. In the 1850’s and 1860’s, the two-volume set of Architecture Civile et Domestique au Moyen et a la Renaissance by Aymar Verdier and Dr. Francois Cattois was well-circulated among architects in England and would have been impossible to elude someone of Burges’ tastes and interests. This was also found in libraries and private collections in the United States with at least one known copy being available in Hartford. In this set, the Hotel-Dieu was the very first building to be analyzed and its roof was the first to be illustrated. What makes this engraving so important is that the dormers were not rendered as an extension of the loggia, but set directly on the continuous eve of the roof. Also, the dormers were rendered with windows rather than being open-aired.

With the Hartford Orphan Asylum, Kimball greatly broadened the application of the style by applying Queen Anne features to an institutional building. Features like the chimneys, the large bay on the nursery, the triple gabled roof and stair tower on the rear of the building show more than just a passing knowledge of Nesfield and Shaw’s buildings since those features are found on their projects including Shipley Hall (1860-61), Leyswood (1866-73) and Cragside (1869-82), to name but a few.

Construction on the asylum began in September 1876 though it was decided that the entire educational wing would not be constructed until the orphanage had grown into its new building. Instead, the rooms on the ground floor of the dormitory were used as classrooms. Within a few years though, the orphaned children were no longer taught at the asylum and were matriculated through the Hartford public school system – an idea that was quite novel and radical in the late 19th century.

The children began moving into the asylum during the first week of October 1878. While the building was under construction, the citizens of Hartford had given quite generously, donating all of the new furniture, school books, clothing, medical supplies, etc.; in fact, the entire $65,000 that it cost to erect the new asylum was completely paid for in donations, with no money having left their treasury. For example, the dining room and all its furnishings was paid for by the Morgan family as a memorial to Sarah Spencer Morgan, one of the asylum’s founders. Also, a single unnamed donor provided all the funds for what was constructed of the stair tower. The builder, Watson Tryon, and the carpenter, John C. Mead, also donated a part of their services, thus reducing the overall cost.

Within weeks of the building’s completion, a review in American Architect and Building News appeared in which the asylum was placed alongside the State Capitol (Richard Upjohn, 1872-79) as being quite influential in expanding the public’s understanding of Gothic architecture as applied to secular buildings. However, even greater praise came the following year when that same publication printed illustrations of the rear elevation as well as a double-page image showing the two principal facades inset with a plan of the ground floor. When Montgomery Schuyler reviewed the building in 1898, he was also quite impressed by the building, citing its reliance on formal gothic elements without the use of “capricious” decorative features. He saw the building as “Kimball’s first independent work of any importance,” and felt it to be an “artistic building that…. aims at such a disposition in mass and such a treatment in detail as to express the arrangement, the material and the construction.”

At the annual meeting in June 1909, the trustees voted to construct the western wing which had been left off in the 1870’s. Rather than constructing an educational wing as was originally intended, Kimball was asked to create a nursery and dormitory instead. However, while Kimball was in the process of redesigning the wing, the trustees began rethinking the overall mission of the asylum, deciding not to construct the wing, instead opting for an experimental cottage where the older girls would be housed and trained in the domestic arts since many of the girls leaving the asylum often found work in various homes in the area.

The architects for the new cottage were H. Hilliard Smith (1871-1948) and Roy D. Bassette (1881-1965), whose partnership had only been formed for about six months when they were hired. The success of the cottage was apparent from the moment that the girls occupied the building in the summer of 1912. Not only were their living accommodations increased in size and comfort, but they were also being trained in practical skills. In 1919, the orphanage was offered about sixteen acres just northwest of the city. Their intent was to operate the entire asylum with cottages. In 1920, their Putnam Street building and property were sold to Mr S. P. Avery for $150,000 though they would continue using the facility until the new cottages were completed.

On June 9, 1922, Grosvenor Atterbury of New York was announced as the architect for the new cottages. Construction began later that summer and was completed in 1925 with additional cottages constructed in 1928. Between January and May 1825, the seventy-eight children in the care of the orphan asylum were gradually moved to their new cottages and the building on Putman Street was left to its new owner. Mr. Avery sold the Putnam Street property to the Hartford School District in 1928 and it sat vacant until 1934. By that time, the building and grounds had fallen in to a state of disrepair it was regarded as a nuisance in the neighborhood. With outcry over the condition of the property, the building was demolished in the summer and fall of 1934. However, bricks and stones were salvaged from the building and were used the following year in the construction of retaining walls along the Park River in the eastern edge of Bushnell Park. Today, the Burns Latino Studies School sits where the asylum had for almost sixty years.

Further Reading:

- “The New Orphan Asylum,” Hartford Courant (Aug. 29, 1877): p. 2

- “Hartford Orphan Asylum,” Hartford Courant (Jan. 7, 1878): p. 2.

- “The Hartford Orphan Asylum,” Hartford Courant (Sept. 26, 1878): p. 2.

- “The Hartford Orphan Asylum,” Hartford Courant (Nov. 9, 1878): p. 2; “The Hartford Orphan Asylum,” Hartford Courant (June 14, 1879): p. 1.

- Chetwood, “Correspondence. The Hartford Orphan Asylum,” American Architect and Building News vol. IV, no. 152 (Nov. 23, 1878): p. 174.

- Commemorative Biographical Record of Hartford County, Connecticut, Containing Biographical Sketches of Prominent and Representative Citizens and of Many of the Early Settled Families (Chicago: J. H. Beers & Co., 1901).

- Grant, Ellsworth Strong and Grant, Marion Hepburn, The City of Hartford 1874-1984: An Illustrated History (Hartford: The Connecticut Historical Society with the Society for Savings, 1986).

- Nesfield, W. Eden, Specimens of Mediaeval architecture Chiefly Selected from Examples of the 12th and 13th centuries in France & Italy (London: Day and Son, 1862).

- “Orphan Asylum at Hartford. F. H. Kimball, Arch’t,” American Architect and Building News vol. 6, no. 186 (July 19, 1879): 2 plates.

- Robson, Edward Robert, School Architecture being Practical Remarks on the Planning, Designing, Building, and Furnishing of School-Houses (London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1874).

- Shaw, Richard Norman, Architectural Sketches from the Continent. Views and Details form France, Italy, and Germany (London: Day and Son, 1858).

- Trumbull, J. Hammond LL.D., The Memorial History of Hartford County Connecticut 1633-1884 vol. 1 (Boston: Edward L. Osgood Publisher, 1886.)

- Verdier, Aymar and Cattois, Dr. Francois, Architecture Civile et Domestique au Moyen Age et a la Renaissance (Paris: A. Morel et Co., 1855).

- Viollet-le-Duc, Eugene-Emmanuel, Dictionary Raisonne de Architecture Francaise du XIe au XVIe Siecle, Tome Sixieme (Paris: R. Bance, Editeur, 1872).

- The Will and Codicils of David Watkinson of Hartford, Conn. Died, 13th December, 1857, Aged 80 Years (Hartford: Case, Lockwood and Co., 1858).