As construction was moving forward on Seabury and Jarvis Halls at Trinity College, Francis Kimball would find himself entangled in two projects which highlighted problems faced by architects as the profession struggled to gain legitimacy– one would play out in the local press while the other was elevated into the national debate over the relationship between architects and contractors.

In June of 1877, Kimball was asked to design a new school house for the South School District in Hartford. Following the Civil War, Hartford’s south side developed rapidly putting tremendous pressure to construct a second school house. The process for securing the building site was quite convoluted and contentious, creating long-lasting animosity between the community, the building committee and the school board.

In the previous summer of 1876, a committee of five prominent citizens was tasked with locating and securing an appropriate site for a new schoolhouse. Within months, the committee held a public meeting to present a variety of sites for their consideration. After extensive debate, they were unable to reach a two-thirds consensus, so it was agreed to solicit a group from the town of East Hartford to consult on an appropriate site and cost for the new school. A bit of confusion ensued since it was unclear whether their decision was binding or if they were only providing recommendations. The one location that proved most favorable was also the most expensive to secure. This was called the Bulkeley-Penfield lot, referring to the two men who owned the majority of the site. After months of negotiations, the owners agreed on a lower price and offered to pay for other improvements to the site. Now that the site was secured, it was time to hire an architect. Unfortunately, this process also proved to be just as contentious as choosing the site.

Kimball was probably approached in June though the nature of his appointment was also riddled with confusion as to what his exact responsibilities would entail. Apparently, he was hired to create a preliminary plan in order to get community feedback and to get a sense of an appropriate budget. Kimball presented his plans on July 7, 1877, which were promptly rejected as being too expensive and by the end of the meeting, it was agreed that the budget would be set at $20,000. In the following months, the school board entertained plans from six architects though it is unknown whether Kimball participated.

Plans submitted by George Keller were adopted in September, but those too were later rejected and for some reason, the following month Jacob Bachmeyer was appointed architect and the school district soon awarded contracts for the masonry and carpentry. As for Kimball, the nature of his appointment was clouded in such confusion that he brought a lawsuit against the school district. The suit went through numerous hearings in superior court and would not be resolved until 1881. The ultimate decision in that case, however, is unknown.

The problems with the South School District were not unique to Kimball or to Hartford and highlighted issues that architects faced as the profession struggled to gain legitimacy. The following year, in 1878, Kimball was asked to design a new building to house the Connecticut Theological Institute (later known as the Hartford Seminary; now known as the Hartford International University for Religion and Peace). With this project, Kimball would once again find himself embroiled in controversy, however this time the problems would play out in the national press rather than in the courts.

The Connecticut Theological Institute was founded in East Windsor, Connecticut in 1834 as a direct result of a split among the Congregational churches known as the Taylor/ Tyler Controversy which was centered around the nature of sin. The entire debate began in 1828 when Dr. Nathaniel Taylor, a professor at the Yale Theological School in New Haven, gave a sermon where he argued that “moral depravity” was a human invention based on free choice. He continued by stating that all people were born into sin and were later saved by their acceptance of Christ as Savior.

After learning of these views, Dr. Bennett Tyler (1783-1858), pastor of the Second Congregational Church in Portland, Maine and former president of Dartmouth College, wrote a letter which criticized Dr. Taylor on the grounds that his beliefs were flawed since they relied on a philosophical debate rather than Biblical history. In short, Dr. Tyler believed that the story of the fall of Adam and Eve showed that people were not born into sin, but were led into it.

This unresolvable debate, which still has resonance today, led to the formation of the Pastoral Union in 1833. This was a group of Congregational pastors and church officials, mostly from Connecticut, who were quite disturbed by this “philosophical” direction espoused by the Yale Theological School and argued that Yale had become disconnected from the ministers and churches in Connecticut. Another point that presented concern was that the divinity school was governed by too many politicians rather than by people within the Congregational Church, thus the faculty was becoming too secular.

Following that first Pastoral Union meeting in 1833, it was decided that a new theological school needed to be established. Some had recommended that it be placed in either New Haven or Hartford, but both were quickly dismissed as it was agreed that the school could best serve its students away from the cities where sin and corruption (and women) could distract the students from their biblical studies. As models, they looked at Andover Seminary which had been established outside of Boston, Princeton Seminary outside of New York and Philadelphia, and Lane Seminary outside of Cincinnati.

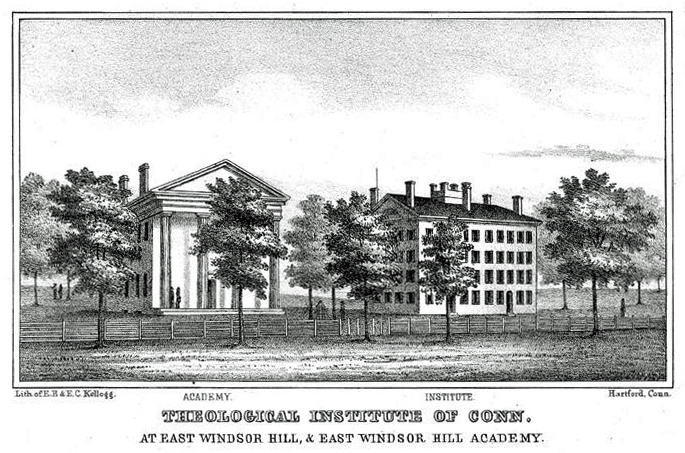

Land was purchased on East Windsor Hill in a remote location northeast of Hartford along the Scantic River and in 1834, the Pastoral Union chartered the Connecticut Theological Institute. The cornerstone for their first building, a dormitory with classrooms, library and a makeshift chapel was laid on May 14, 1834 and the building was ready in January. In 1844, the institute began canvassing for funds which eventually led to the dedication of their new chapel on August 8, 1847.

Through the 1830’s and 1840’s the school was rather stable, but during the 1850’s, there was a precipitous decline in enrollment. With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the school could neither attract students, nor hold the ones they had. By 1863, the school was in a crisis and two years later, Pliny Jewell of Hartford agreed to lease the former Daniel Wadsworth house at 48 Prospect Street in Hartford to the institute for $1,000 per year.

In August 1865, the Connecticut Theological Institute closed their buildings in East Windsor and formally moved to Hartford. This move put the school just two blocks from the heart of Hartford’s business district and three blocks from the red light district – right into the belly of the beast by the standards of their founders. In contrast, though, they were also located only one block from the First Church of Christ, one of the oldest, largest and most influential Congregational churches in Connecticut.

Following the civil war, the theological institute found that some of its former students were willing to return and that it was easily attracting new students. The house at 48 Prospect Street soon proved to be too small, and over the next decade, the seminary expanded into four more houses along the same street. Students who had studied at their campus in East Windsor often complained that the facilities in Hartford were very cramped and poorly adapted for classroom learning. This would soon change.

In May of 1877, the Institute announced their intentions to erect a new seminary building on Broad Street near Farmington Avenue. It was not until the following year, however, that the school was given a generous gift by James B. Hosmer (1781-1879) allowing the institute have their own campus for the first time since moving to Hartford and the new building would be named in his honor. Hosmer had been a founding member of the institution in 1834 and had remained active in its growth and move to Hartford.

The search for an architect formally began on April 2, 1878. Though other architects answered the call for designs at that time (most notably, George Gilbert), it was not until May 18th when Kimball presented plans. His designs obviously impressed the committee since he was then asked to meet with various faculty members to revise the plans. By August, the plans had progressed far enough that excavations had begun on the gymnasium which was a detached structure set behind the main building on the southwest corner of the seminary grounds.

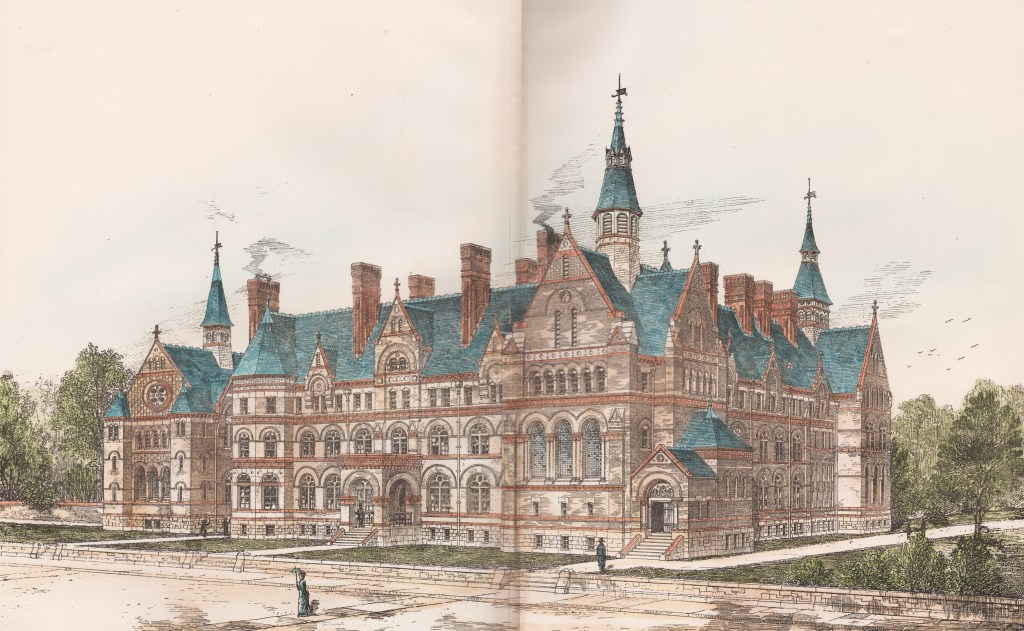

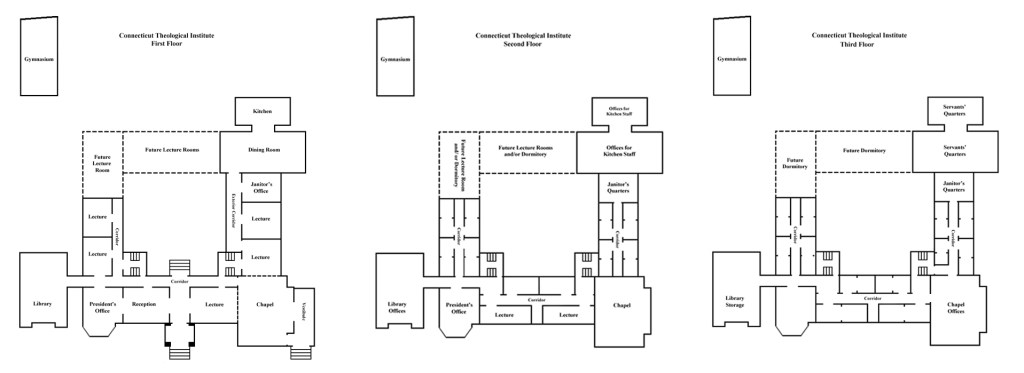

For the main complex though, Kimball’s plans were for a large U-shaped structure forming three sides of a quadrangle which could have its fourth side constructed later. This was to be built of brick with light colored stone coursing, arched windows on the lower floors and gables, decorative chimneys and tall, gothic vents articulating the library, chapel and dining hall. The main part of the building was the eastern wing set along Broad Street with the chapel to its north and a semi-detached fireproof library on the south. At the intersection of the east and north wings stood the chapel. Behind the alter were three tall, arched windows which looked out over Broad Street. The chapel was entered in the front of the building as well as through the lecture rooms in the adjacent wings, large doors could then be folded open, expanding the chapel into the two adjacent lecture rooms. At the western end of the north wing was the dining hall, off of which was the kitchen and servants’ quarters. Like the library, the kitchen was also to be semi-detached and fireproof.

The southern wing, which ran parallel to the northern, housed lecture halls and a professors’ study on the first floor. The uppermost floors throughout the building were for student accommodations while the first and second floors were lecture halls. Like the Hartford Orphan Asylum, Kimball placed fireproof stairwells outside of the main structure at the corners where the wings intersected.

The primary feature that set this building apart from other college buildings of the period was that the most of the building was serviced by long, wide corridors, allowing the students and faculty to roam from room to room without leaving the building. The exception to this was the north wing, which had a long porch connecting all rooms from the outside. The long walk at Trinity College was a good example of traditional planning where there were no interior corridors and all exterior doorways lead directly into stairwells.

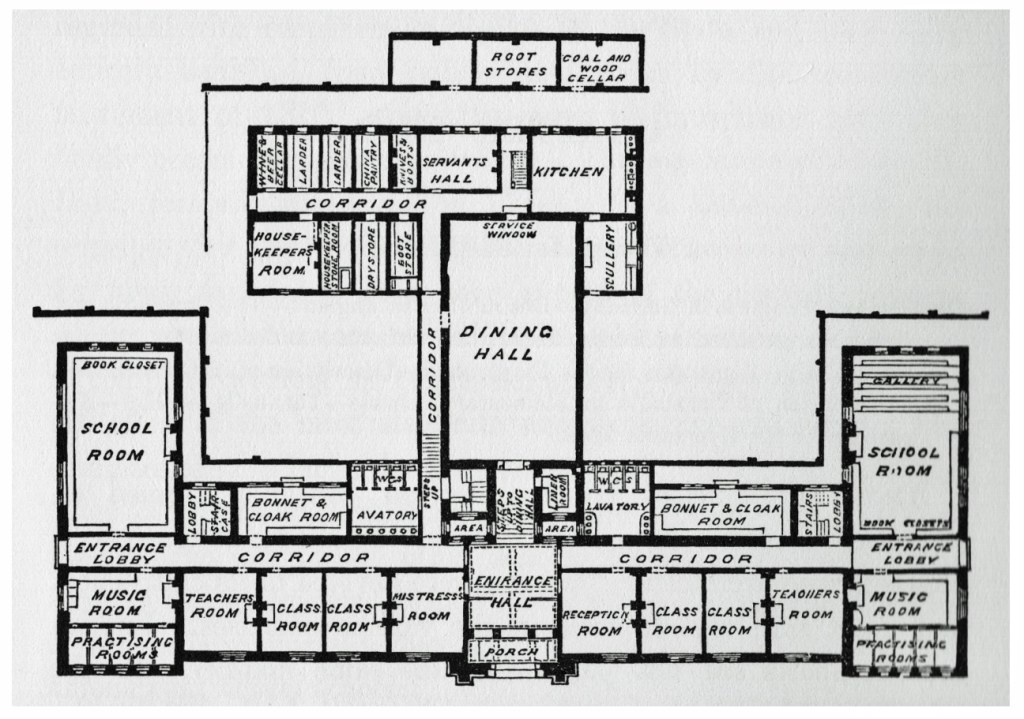

Right: Plan for St. Scholastica Benedictine Convent, Teignmouth, Devon, Eng., G. Goldie, arch., 1863.

Kimball first employed interior corridors at the Hartford Orphan Asylum and the his plans for the theological institute owes much to that earlier building. This idea, however, was not original to Kimball since it was already well established in England with buildings such as St. Scholastica Benedictine Convent, Teignmouth, Devon (G. Goldie, arch., 1863) and Walton Hall in Warwickshire (George Gilbert Scott, arch., 1860), a building whose plan was striking similar to that of the theological seminary. With this plan, Kimball also continued to rely on Milton Mount College with its corner stair towers though the dining hall was moved to the northwest corner of the plan. Like the Milton Mount College plan, Kimball placed a one-story corridor running along the northern wing, terminating at the dining hall.

Stylistically, Kimball drew heavily from details not only from Burges’ early plans for Trinity College, especially from the theatre and art gallery, but also from “Knightshayes,” (1867-74) the residence of Sir John Heathcoat Amory near Tiverton, Deven, England, designed by Burges in 1867 and completed in 1874 while Kimball was in London. Locally, Kimball was inspired by H. H. Richardson’s recently completed Cheney Building for the groups of tall, arched windows on the library, chapel and dining hall.

Throughout August and September 1878, Kimball continued the revisions and on October 1, presented the final plans for the gymnasium. On October 4, the contract for the construction of the gymnasium was awarded to builders John Hills and John Garvie. This was where Kimball’s troubles began. In a rather suspicious scenario, John Hills was listed as the builder a week before Kimball presented plans and began accepting bids from various builders. To make matters even worse, John Garvie had been known to boast that, “…he gets rid of the ‘architect’ as soon as the plans are finished.” Once construction began on the gymnasium, Hills and Garvie completely altered Kimball’s design.

During the fall and into February 1879, Kimball continued to revise the plans for the campus. By the end of February, he had been relieved of his duties as architect principally on the grounds that his designs would be too expensive to construct. Apparently, the builders stated that their intentions were to “save money”, though they would not allow outside estimates as a comparison. As the seminary rose to completion, Kimball was able to obtain estimates that were around $90,000; well below the Garvie’s original estimate of $104,862.

The foundations for Hosmer Hall as well as the the general scale and massing as well as much of the interior plan definitely reflected Kimball’s design. However, with the help of architect John Correja (1826-1910) of New York, the builders had discarded the exterior details in favor of a simpler, sober design.

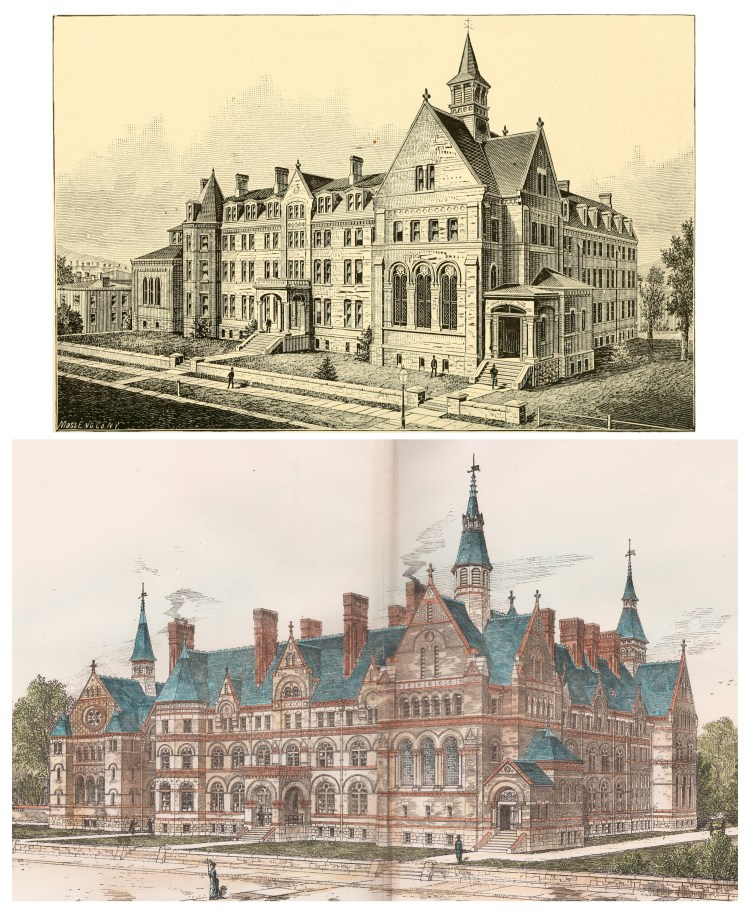

Bottom: Original design by Francis Kimball, 1878-79.

While working as a draftsman in the office of Bryant & Rogers in the late 1860’s, Kimball had been taught to differentiate parts of a building by varying the fenestration and his design for the Connecticut Theological Institute was no exception. In his original design, Kimball had employed groups of tall, arched windows for the library, chapel and dining hall while other college functions such as lecture rooms and offices were also given arched windows. On the top floor, Kimball employed rectangular sash windows to denote the students’ living spaces. To further articulate the larger spaces, Kimball placed square ventilation towers over the library and dining room with a taller, octagonal tower signifying the that the chapel was the most important space in the building.

When the exterior was simplified by the new architect and builders, the building lost most of the window variation that signified the different uses throughout the campus. Basically, it appears as though they maintained Kimball’s scale, massing and plan, though they only erected one rear staircase which stood at the chapel intersection. Other changes included eliminating the dining hall and kitchen and completely changing the design for the library which sat at the far left in the plan.

Other changes included reducing the number and size of the chimney stacks and constructing a mansard roof with simple wooden dormers, essentially adding a fourth floor designed for student dorms. Other changes to the roof-line included eliminating two ventilation towers while greatly simplifying and reducing the height of the tower over the chapel. Other features eliminated from Kimball’s plan were the courses and accents which were to be constructed with decorative terra cotta.

As for the interior, Its rather difficult to discern what changes were made by the builders. Photos held in the archives of the Hartford Seminary show the original designs to many of the rooms. Though a couple rooms seem to have similar woodwork found in other Kimball buildings, many of the details do not seem to be from his designs. More than likely, Kimball’s dismissal from this project probably happened before he had began to design most of the interior features.

When the cornerstone was laid on May 8, 1879, no mention was made of Kimball and a year later when the Hosmer Hall Chapel was dedicated on May 13, 1880, Kimball’s name did not appear on the program though it was stated that when the plans were obtained in February 1879, “they were declared not satisfactory, and abandoned.” Kimball friend William Brocklesby, who was an architect and journalist, had been reporting on the progress of this project since its inception. It was through his articles published under the pseudonym “Chetwood,” in American Architect and Building News that brought national attention to this project. Since this reflected the often tenuous relationship between builders and architects, Kimball was actually asked by the publication editors to submit the final rendering of the building which was prominently displayed in a two page spread published in their November 15, 1879 issue.

Whereas Kimball’s problems with the South School District were played out in superior court, the issues with the Connecticut Theological Institute were put on public display in the local newspapers and as well as in American Architect and Building News. For this project however, Kimball did not have to involve lawyers since the seminary fully reimbursed him with timely payments to a total of $1350.00.

In 1913, the seminary purchased property on Girard Avenue at Elizabeth Street and hired Day & Klauder of Philadelphia as consultants to advise on removing the seminary from Broad Street. By 1920 the seminary had outgrown its campus, especially since they had no facilities for house female students. The following year, Day & Klauder announced their new plans which consisted of three separate quadrangles rather informally arranged. Over the next few months, however, those plans were laid aside, and in November, Allen & Collens of Boston were named as architects and would eventually design twelve buildings for the new campus. In 1978 the seminary hired New York architect Richard Meier to design its current facility and the Elizabeth Street campus was sold to the University of Connecticut Law School.

As for the building on Broad Street, Hosmer Hall and its surrounding property was transferred to the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) in 1925, and the following year, the seminary formally moved to its new campus. Demolition on Hosmer Hall began in October 1926. That month, architect Roy D. Bassette of the local firm Smith & Bassette presented plans for the new YWCA building. The entire site was not cleared, however, and the women continued to use the library, museum and gymnasium buildings until the 1960’s when those remaining buildings were demolished to build the current YWCA building.

I would like to thank Steven Blackburn, Archivist of the Hartford Seminary for all his assistance in locating the dusty materials buried in the seminary’s archives as well as sharing his knowledge of the seminary’s illustrious past.

Further Reading:

- Chetwood. “Correspondence: The Connecticut Theological Institute and Its Architect,” American Architect and Building News vol.6, no.194 (September 13, 1879): p. 85.

- Connecticut Theological Institute, “Checks, May 1878-November 1879.”

- Connecticut Theological Institute, “Prudential Committee Records 1873-1918.”

- Connecticut Theological Institute, “Treasures Ledger 1875-1894.”

- “Connecticut Theological Institute, Hartford, Conn. F. H. Kimball, Arch’t,” American Architect & Building News vol. 6, no 203 (Nov. 15, 1879): plate.

- Geer, Curtis M., Hartford Theological Seminary:1834-1934 (Hartford, 1934).

- Hartford Theological Seminary: Services at the Dedication of Hosmer Hall Chapel (Hartford: Case, Lockwood and Brainard Company, Printers, 1880).