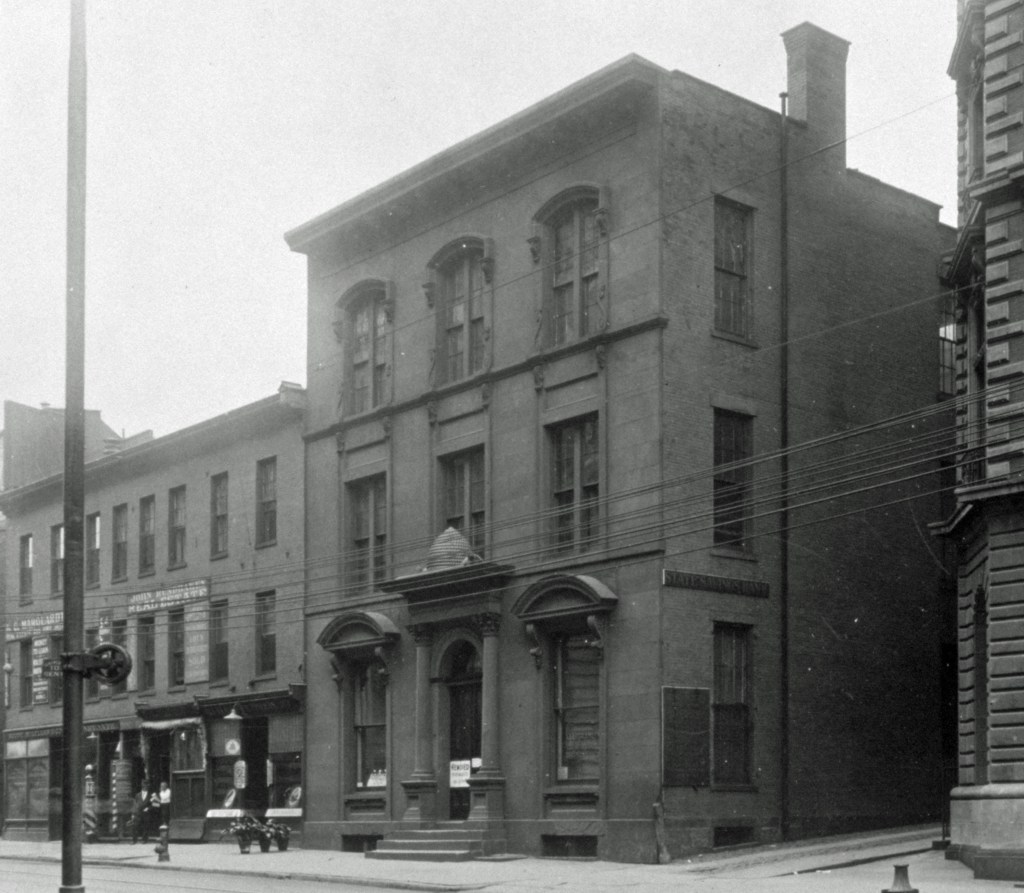

By 1879, Kimball’s practice was really taking shape. Seabury and Jarvis Halls as well as the Hartford Orphan Asylum had all been completed, and other smaller commissions were underway. In mid-January, Kimball had moved his office out of Seabury Hall and into the second floor of the State Savings Bank building at 39 Pearl Street, across from the Connecticut Mutual Life Insurance Building in downtown Hartford. It is quite possible that he shared an office with William Brocklesby since both men opened their offices in the same building on the same date. Though there is no evidence that the two men ever collaborated, they had developed a good friendship and since Brocklesby (under the pseudonym, “Chetwood”) was the Hartford correspondent to American Architect and Building News, he had been quite instrumental in enhancing Kimball’s reputation. Also, by looking at buildings designed by Brocklesby in the late 1870’s and early 1880’s, it is easy to see how Kimball had a direct influence on the younger architect.

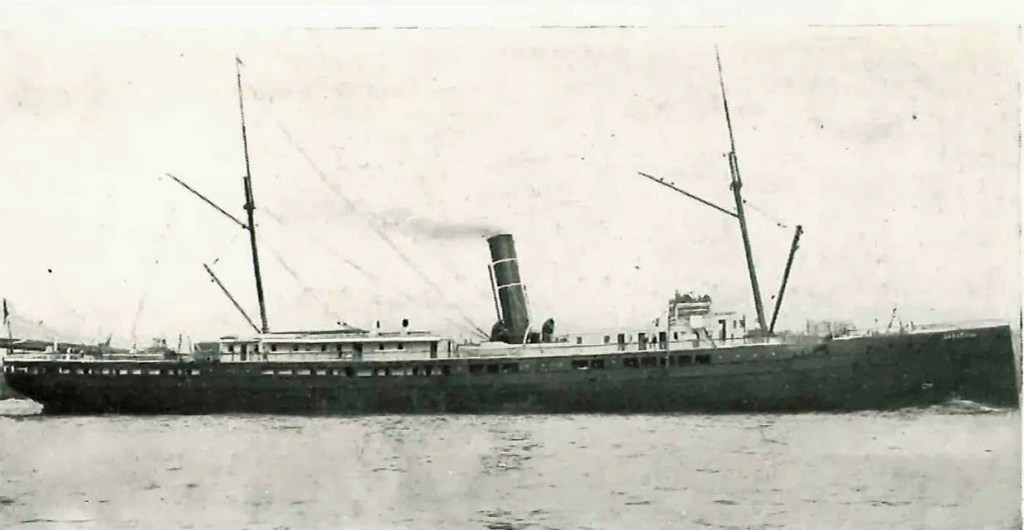

Shortly after opening his new office, Kimball took a few weeks off and sailed the steamship Saratoga from New York City to Havana, Cuba, accompanied by his brother-in-law, Josiah Littlefield who had trained Kimball as a carpenter from the late 1850’s through the mid 1860’s. Also travelling with them was Watson Tryon, a Hartford contractor with whom Kimball had worked on a variety of projects.

The time off must have been quite good for Kimball and being able to spend extra time with the two men allowed him to think about some of the recent trends emerging within the profession. And it would not take long for Kimball to have opportunities re-examine his thoughts on commercial design.

On the evening of March 15, 1878, James Goodwin had died suddenly while traveling home along Asylum Street. Since Kimball’s arrival in Hartford in 1868, Goodwin had been quite instrumental in the development of his architectural career most notably with Connecticut Mutual, Trinity College and the Hartford Orphan Asylum. Kimball had become quite close to the Goodwin family, especially after 1873 when he traveled to London along with Goodwin’ son, Rev. Francis Goodwin (1839-1925).

The young Reverend had been the rector of Trinity Church in Hartford from 1865 until 1871 when he left to pursue business interests. That year he began designing his father’s house, “Goodwin Castle,” with Frederick Withers of New York and would later design a handful of churches and residences throughout the region. Rather than those buildings, though, Goodwin is perhaps best remembered for his active participation in developing Hartford’s park system (Goodwin Park is named in his honor), the founding of the public library and the erection of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument in Bushnell Park (George Keller, arch., 1882-86).

With the death of James Goodwin, Rev. Francis and his brother James, Jr. immediately became the executors over the family’s extensive real estate holdings which had been amassed over generations. The brothers would continue their father’s legacy by extending the family’s real estate holdings while contributing greatly to Hartford’s continued development.

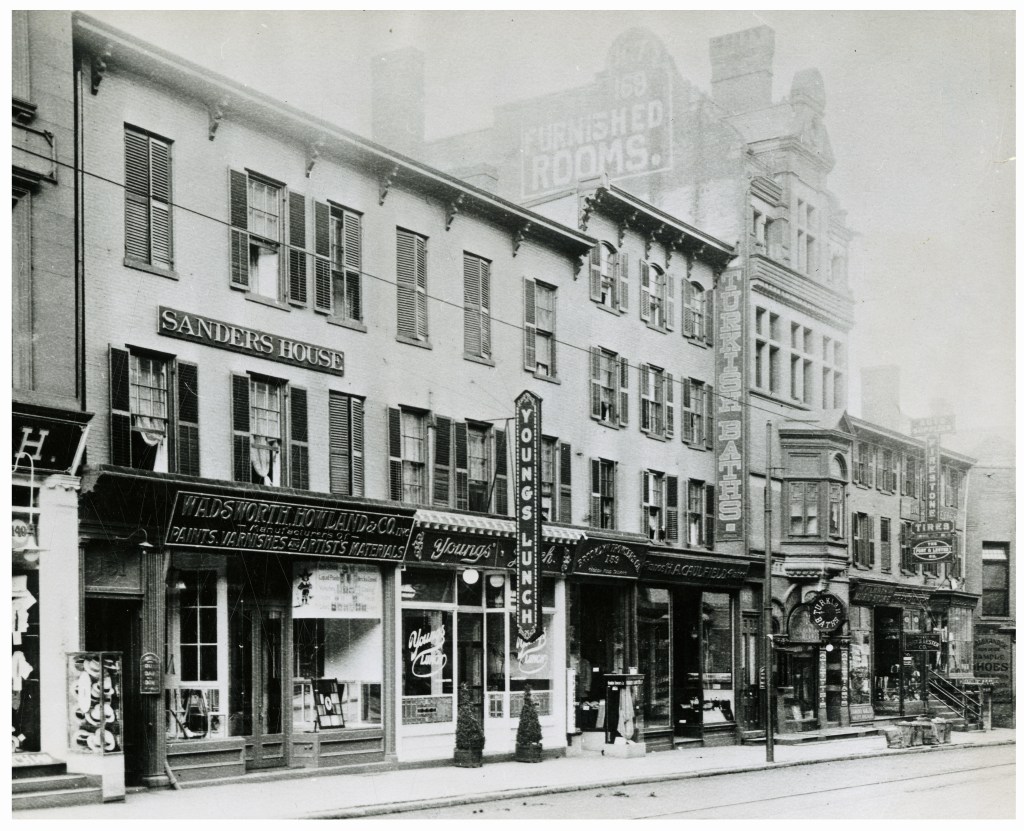

What was perhaps their earliest foray into redeveloping a property within Hartford’s business district came in May or June of 1879 when they hired Francis Kimball to design a four-story commercial block on Asylum Street, very near the location which James Goodwin had died the previous year. Francis Goodwin obviously wanted a commercial structure intended to attract businesses that catered to various arts and design while showing an awareness of recent developments in larger cities like New York and London where the Queen Anne style was gaining momentum over the waning Gothic Revival, pointing to a lighter, freer and more delicate approach to commercial design.

The Goodwin Building was four stories and constructed of iron, brick and Nova Scotia granite and was described as being, “pervaded by the ‘Queen Anne’ feeling…… form[ing] a pleasing contrast to the average public building in the city.”. On the ground floor was a large display window with entrances on either side. Over the window and entrances were three elliptically arched transoms filled with stained glass. On the second floor was a pedimented, oriel window supported by a heavy stone bracket and augmented with stained glass with quasi oriental details above the sash windows. On either side of the oriel were very thin, stained glass windows. The third floor was simply designed with three pairs deeply recessed, transomed windows with stained glass ornamenting the transoms. Between the third and fourth floors was a bold, stone cornice. The top floor was given a tall dormer with a pair of transomed windows with a double pediment above. Within the lower pediment was an ocular window. Though this was a four-story building, a basic comparison to its four-story neighbor to the left shows the ceiling height on the upper floors was quite high, allowing for greater amounts of natural light.

Kimball had integrated a few Queen Anne details in his design for the Hartford Orphan Asylum, and the same can be said with the design for the Goodwin Building. Though he was not fully embracing the style, details such as the oriel window and and the double-pedimented dormer showed that he was clearly integrating aspects of the burgeoning style in a manner that softened the predominantly bolder aspects of the building’s facade.

During the nine months he spent in London, Kimball would have seen various designs by Richard Norman Shaw, William Nesfield, E. W. Godwin, Basil Champneys and scores of other young architects who were developing and solidifying the style in the 1860’s and 70’s. Closer to home, however, many east coast architects had begun experimenting with the style, though it was limited mostly to seaside and suburban houses. By the mid-1870’s, the style began to take on an urban character as architects in New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Chicago, etc…, began to incorporate Queen Anne details into residential design.

Right: Hampden County Courthouse, Springfield, MA., H. H. Richardson, arch., 1871-74.

About the only commercial examples for Kimball to draw from were in London, especially in the designs of Richard Norman Shaw and Ernest George & Harold Peto, though those did not really serve as very good models. Instead, Kimball seems to have looking at recent American examples such as McKim Mead & Bigelow’s Dickerson House (1877-79) in New York City. The transomed windows on the third and fourth floors however, gave the building a slightly heavier feel, belying the delicacy of the first two floors and seem to be derived from H. H. Richardson’s Hampden County Courthouse (1871-74) in nearby Springfield, Massachusetts.

With this building, Francis Goodwin had intended to attract businesses with artistic interests. T. F. Burke’s art gallery, which took up the entire second floor, opened in April 1880 and was the first business to move into the new building. This was soon followed by artists renting studio space on the two upper floors, some of whom actually taught art classes in the building. In September, the organ and piano dealers, Schoninger & Co., opened on the ground floor.

Except for a couple brief descriptions in American Architect and Building News, the Goodwin Building was basically ignored and had little to no impact on the development of the Queen Anne style in the United States. For starters, the style was predominately light and airy and best expressed with brick and terra-cotta. The Goodwin Building was principally constructed of granite giving an air of ponderous weightiness as if it the details were added to soften the overall appearance of the building. Though it was one of the earliest attempts at giving the Queen Anne style a commercial expression, its awkwardness perhaps revealed that the style just did not have the forcefulness to compete with the burgeoning Richardsonian Romanesque as the dominant commercial style of the period.

The Goodwin Building was demolished in 1972.

Further Reading:

- “A New Building,” Hartford Courant (July 4, 1879): p. 2.

- Chetwood. “Correspondence: New Work,” American Architect and Building News vol. V, no. 183 (June 28, 1879): p. 206.

- Stern, Robert A.M., Mellins, Thomas and Fishman, David, New York 1880 (New York: Monacelli Press, Inc., 1999.