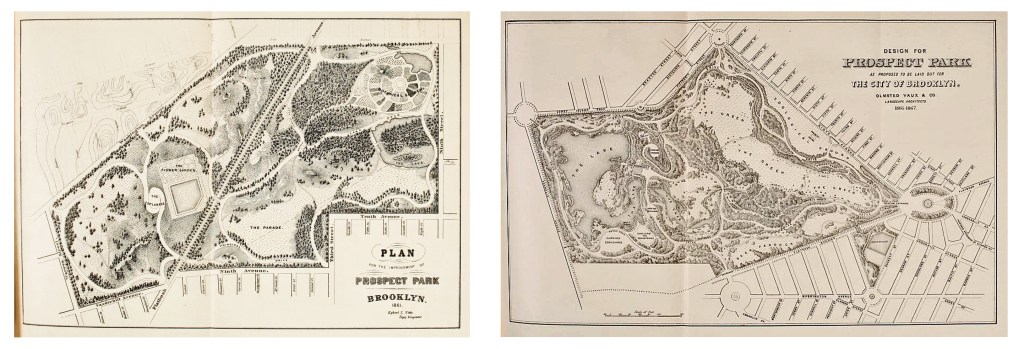

With Olmsted and Vaux’ dismissal as the architects of Central Park in the spring of 1870, Thomas Wisedell also ended his tenure in that park and was given much greater design responsibilities in the creation of Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. Prospect Park had originally been planned in 1861 by Egbert Viele, but due to the Civil War, very little work had been done. As Central Park was progressing, it became clear that Viele’s plan for Prospect Park was unsatisfactory and in 1864, Calvert Vaux was asked to report on recommendations for improvements. Vaux submitted his report in February 1865 and over the summer, he convinced Frederick Law Olmsted to renew their partnership for this project. At that time, Olmsted (along with Edward C. Miller, an engineer and surveyor who had been working with Olmsted and Vaux designing bridges for Central Park) was working in California on the failed Mariposa Estate and campaigning for the creation of Yellowstone National Park. During that period, Olmsted was also working in Oakland, California planning Mountain View Cemetery and the grounds for the University of California at Berkeley.

Right: Plan of Prospect Park , Olmsted & Vaux, 1866-1867.

Olmsted arrived back in New York on November 22, 1865 and within days, he and Calvert Vaux were completing their initial plans for Prospect Park. Unlike Central Park, the Brooklyn Park Commissioners did not want to cater to private interests, instead, opting for a pleasure ground with fewer architectural features. It was this proposal laid out in the Sixth Annual Report (1866) that many historians see as the founding document for the American parks movement since it is there that the guiding principles of Olmsted & Vaux were articulated. Though most of those principles are beyond the scope of this survey, what will be focused on is their understanding of the role of architecture within a park setting while creating “places of congregation and rest.”

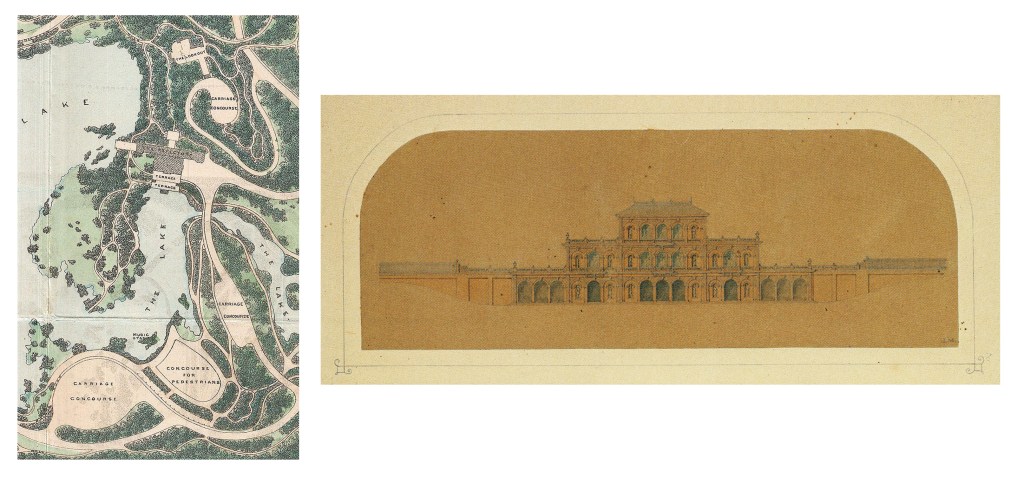

Right: Unbuilt Central Park Garden Arcade Building, 1858.

For Prospect Park, it was intended to have a large refectory in a central location with Lookout Hill to the west and the Music Stand on an island near the Pedestrian Concourse across the bay to the east. The refectory was “proposed to be a house of entertainment on a liberal scale, agreeably situated so far as outlook is concerned, but with no more suggestion of privacy or retirement than would be found in a suburban hotel.” This was to be designed with a broad, five-hundred-foot, arcade overlooking the eastern bay while also creating a vista over the lake. The restaurant was to be in a space two hundred feet wide and one hundred seventy-five feet deep. Below the restaurant would be two levels of arcades with its lowest being at the level of the lake in order to accommodate ice skaters in the winters and boats in the summer. Though this building was probably never fully designed, it is possible to get an understanding of Calvert Vaux’ idea from the unbuilt Garden Arcade Building designed for Central Park in 1858.

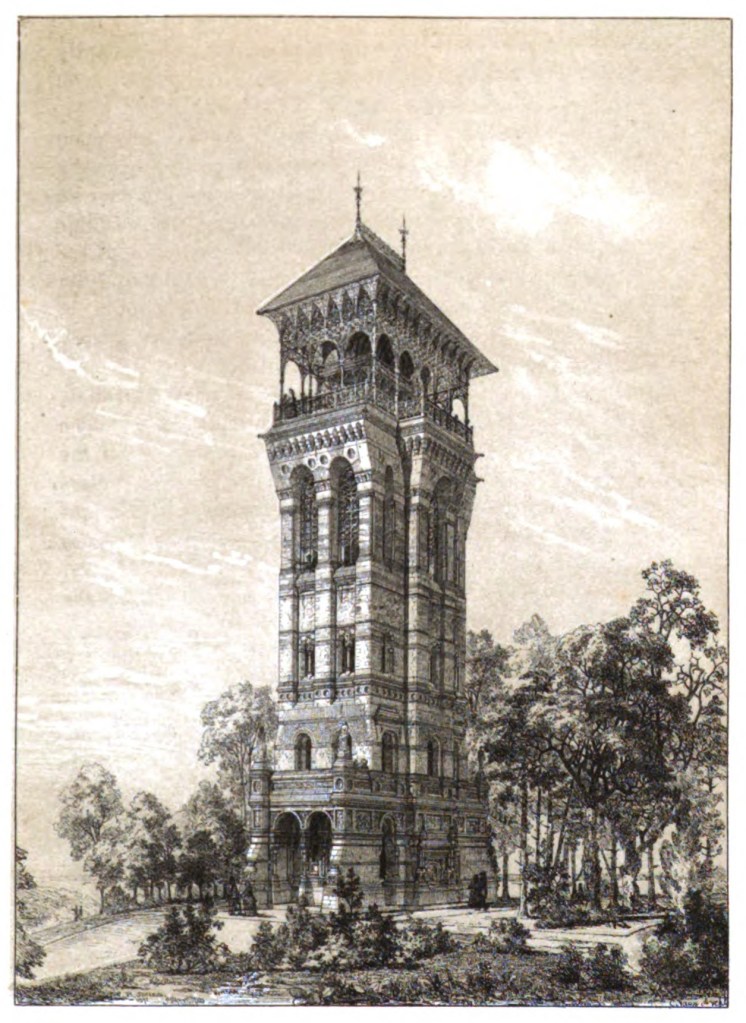

Lookout Hill was the highest point in the park, and was intended to be the ultimate destination since “all principle walks of the park tend to lead the visitor from whatever entrance he starts, to finally reach the Lookout…” The lookout was originally intended have a large, terraced platform at the top of the hill. To the west was a small building to accommodate women and children. Beside the building would be a wide terrace offering views to the south over the Parade Grounds. Just east of the Lookout would be a carriage concourse.

Across the bay from the refectory was the “pedestrian concourse.” This was actually the largest of the three and included a music island, a pedestrian concourse and two carriage concourses. A bandstand was to be designed for the island from which music would be heard wafting the in background through much of the southern part of the park.

Construction on Prospect Park began in the spring of 1866 and by 1870, much of the northern and eastern sections had been graded with bridges, walks, drives and concourses either completed or well under way. Beginning in July 1867, Edward C. Miller had been Vaux’ assistant architect in Prospect Park and together, the two men designed of most of arches and bridges as well as the dairy and large shelter at the adjacent Parade Grounds. By the summer 1869, Miller left Prospect Park to work in Vaux’ private architectural practice and a few years later, he returned to California where he was in charge of implementing Olmsted’s plans in Oakland and Berkeley.

About the time that Miller left Prospect Park, Olmsted and Vaux began reworking Lookout Hill as well as the pedestrian concourse, while the refectory remained just an idea. For the Lookout, the size of the hilltop platform was reduced and a tall tower which was designed by Vaux with Bassett Jones was to be placed between the carriage concourse and the platform. Like the refectory, this feature, would unfortunately also remain unbuilt.

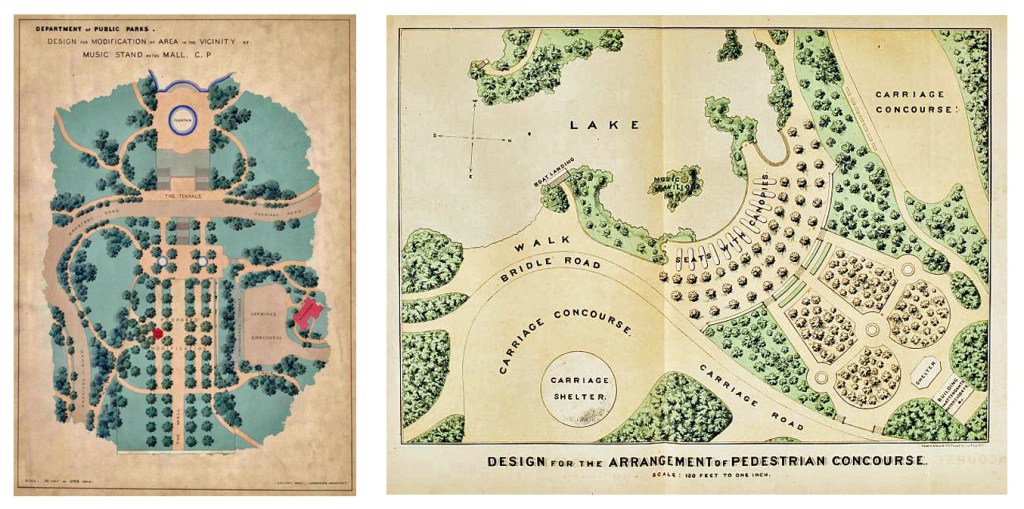

It was with the “pedestrian concourse” (later known as the “Concert Grove”) that Olmsted and Vaux were able to rework what had been an adjunct to the promenade in Central Park into a fuller concept within the landscape. In Olmsted and Vaux’ Greensward Plan for Central Park of 1857-58, they included a Music Hall with a glass Conservatory which had surrounding terraces overlooking the mall from a promontory from the east. When that scheme was not adopted, Olmsted apparently wanted to create a floating pavilion which would slowly move around the lake in Central Park, but that idea was also rejected by the commissioners. Instead, Olmsted and Vaux redesigned the northern end of the mall into a “concert ground” with a bandstand on the west and a long pergola overlooking the mall from the east. Along with the pergola was a carriage concourse and a newly designed ladies pavilion known as the “Casino.” Before long, the Sunday concerts had grown to such popularity that it disrupted the pedestrian concourse while the carriage concourse and casino had also proven to be too small.

Right: Design of the pedestrian concourse at Prospect Park to become the “Concert Grove,” 1870.

With the creation of the “Concert Grove” in Prospect Park, Olmsted and Vaux were able to address most of those problems. At Central Park, the “concert ground” was an after-thought which had to be incorporated into the mall while at Prospect Park, that concept was given its own space and designed to accommodate many more people with far better circulation. To begin with, there were two carriage concourses, one to the east and one to the west on top of Breeze Hill overlooking Music Island.

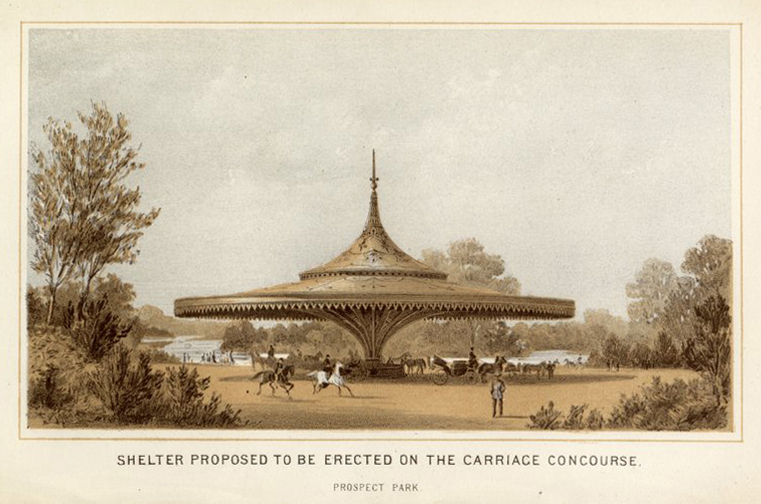

For the larger carriage concourse to the east, Vaux had designed a massive, circular carriage shelter with a large water trough for horses. The purpose of this was not only for those arriving at the Concert Grove, but also as a place where carriage rides could by purchased for traveling through the park. This unbuilt structure was one of the most daring pieces of engineering Vaux had attempted, measuring one hundred feet in diameter. Stylistically, it was quite similar to the Mineral Springs House (1867) in Central Park blending Safavid floral decoration with forms reflecting the northern reaches of the Ottoman empire.

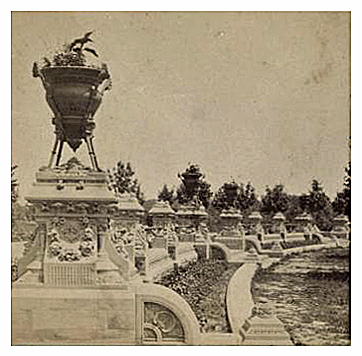

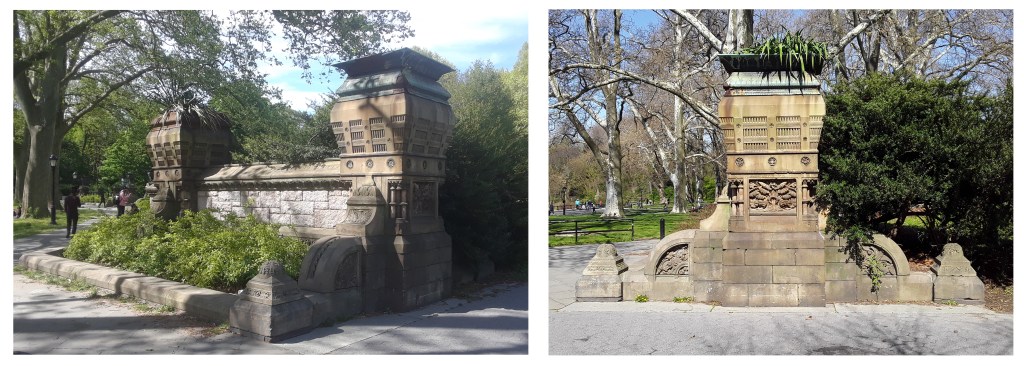

For the Concert Grove, Olmsted and Vaux placed the orchestra on an island where the music could be carried over the lake and along the bay. The concourse itself was designed with an esplanade and terraces connected by walks radiating away from the water. Along the water, canopied seats sat in front of a grove of trees lines of trees planted concentrically to a depth of one hundred and seventy-five feet. Separating this esplanade from the first terrace was a semicircular retaining wall with massive piers supporting bronze planters. For this terrace, piers were designed with an exotic mix of Greek, Italian, Indian and Moorish designs with musical tributes ornamenting the four smaller piers.

Separating this esplanade from the first terrace was a semicircular retaining wall with massive piers supporting bronze planters. For this terrace, piers were designed with an exotic mix of Greek, Italian, Indian and Moorish designs with musical tributes ornamenting the four smaller piers.

Left: Concert Grove planters and piers, 1874.

(1) Lyre with sheet music. Possibly a tribute to Franz Hoffmeister; (2) Trumpet with sheet music to Verdi’s Il Traviata (The Troubadour);

(3) Violin and flute in tribute to Mozart ; (4) Piccolo Oboe with Piccolo and Trompe de Lorraine. Tribute to unknown composer.

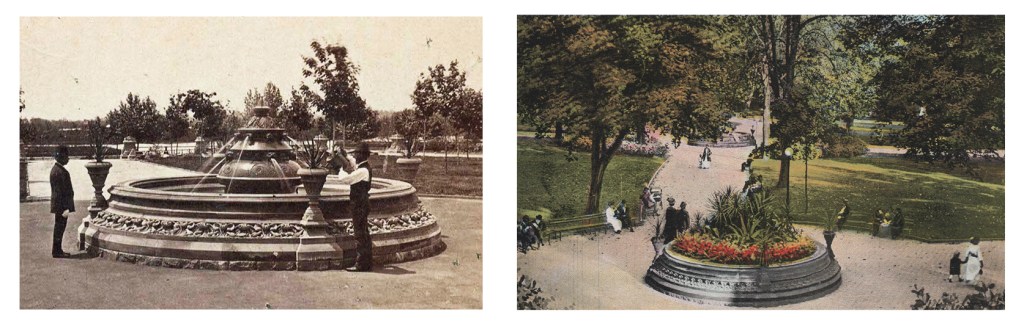

Behind the piers and planters, the terrace was divided by three walks leading to two, massive circular, granite planters centered by a fountain designed in a similar style. Like the other architectural features in the concert grove, these too were designed by Calvert Vaux while their detailing and ornamental work were designed by Thomas Wisedell, though the fountain may have had part of its decoration designed by Bassett Jones.

Right: Postcard showing circular planter ca. 1904.

Right: Detail of the Cleft-Ridge Span designed by Bassett Jones.

Just east of the circular planters was another entrance into the Concert Grove which also served as a viewing platform for parades along the concourse. This was designed with large piers similar to those at the esplanade, but here were much larger semicircular panels which had been designed by Thomas Wisedell. It is with those panels where it is most easily understood what he had learned from Jacob Wrey Mould in the Central Park Terrace.

Bottom Images: Panels from the Concert Grove, Prospect Park designed by Thomas Wisedell, ca. 1870 and installed 1872.

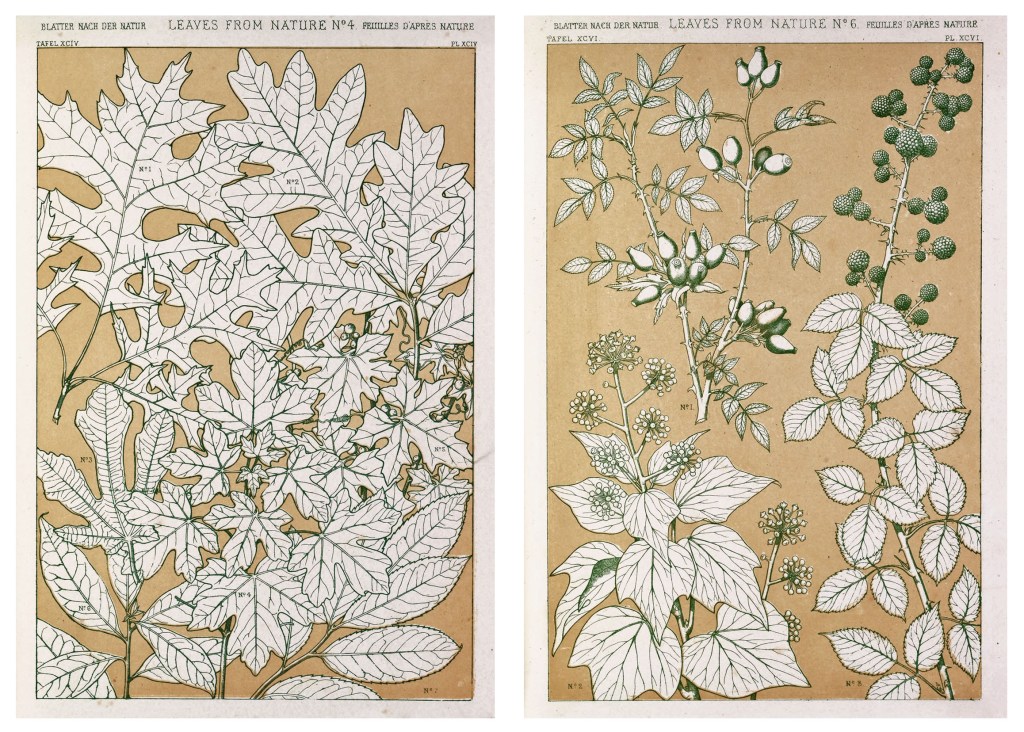

As stated in an earlier post, Mould is credited with bringing the design ideals of Owen Jones to the United States. The style of decoration for the the stonework originated with Jones in Britain and both styles of designing from nature can be found in The Grammar of Ornament. Though that book was published in 1856, Jones had clearly been developing his naturalistic ornamental style since the early-mid 1840’s.

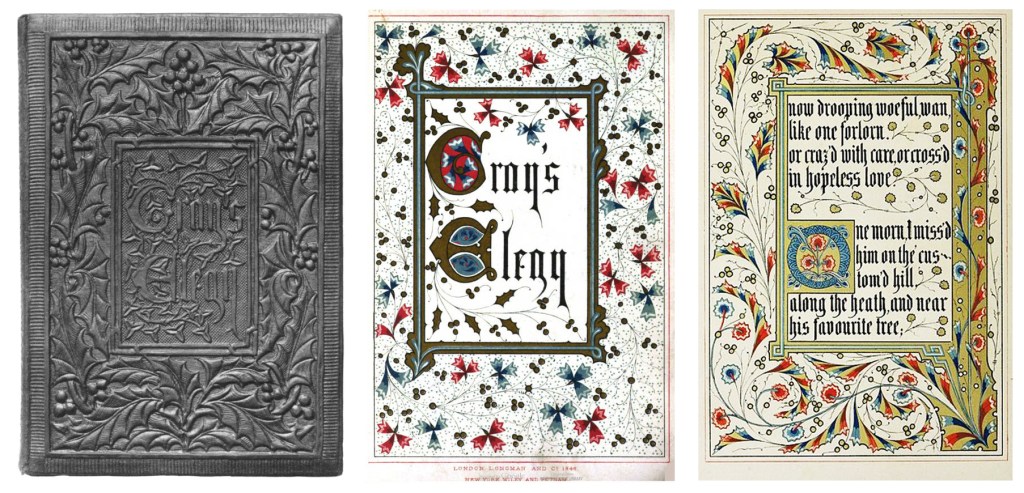

Jacob Wrey Mould probably began working For Owen Jones in either 1842 or 1843 and is best known for assisting with the illustrations for the second volume of Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details of the Alhambra (1845). Though Moorish influences are clearly on display in both Central Park and Prospect Park, Jones was a rather prolific illustrator of books, and it is known that in addition to his illustrations for The Alhambra, Mould also assisted in the creating illustrations for The Book of Common Prayer (1845) as well as Thomas Gray’s Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (1846), better known as Gray’s Elegy.

Though The Alhambra was his most famous book from the 1840’s, it was with his designs for the numerous books also published around the same time where Jones was instrumental in reviving medieval designs inspired by nature. These designs would soon evolve into architectural decoration which when brought to the United States, proved to be the perfect language to give form and add fuel to the already thriving Transcendentalist Movement. With the advent of the American parks movement, Jones’ aesthetic philosophy found the perfect vehicle through which Jacob Wrey Mould could elevate design in America. Thomas Wisedell’s designs for ornamenting the Concert Grove show that he had fully absorbed the design ideals of Jones and Mould and was fully capable of applying their lessons.

Just as important to the designs for the Concert Grove was the masterful execution of the stonework and bronze planters. The firm of Robert Ellin & Co. was hired to do the carving while Janes & Kirtland manufactured the bronze work. Robert Ellin (1837-1904) was trained in the art of wood and stone carving at the offices of Rattee & Kent of Cambridge, England. He immigrated to the United States in 1867 and worked with James Whitehead to produce some of the larger carved panels at the mall in Central Park (see part 2a). In 1871 he established the firm of Robert Ellin & Co., and with his partnership with William Kitson in 1874 the name was changed to Ellin & Kitson. It was that firm that quickly evolved into the largest atelier in the United States for training wood and stone carvers attracting apprentices from almost every country in Europe as well as Russia.

The carvings for the Concert Grove played a large role in the formative years of Robert Ellin’s company since most of his work in the early 1870 were for the interiors of private residences and primarily consisted of wood carving. The Concert Grove was perhaps the first large scale public work that the firm created and it was the work at both Central Park and Prospect Park that represent the arrival of professional carvers in the United States, with architects and contractors no longer relying on works having to be carved in Europe.

As for the bronze works, Janes & Kirtland was one of the oldest foundries in the United States, having been founded for Adrian Janes in New York City in the 1840’s. Like Olmsted, Janes was also from Hartford, Connecticut. The firm quickly gained a reputation for large scale commissions and in 1861 began work on casting all of the parts for the dome over the United States capitol in Washington, D.C. Previous to their work at the Concert Grove, Janes & Kirtland had produced all of the work for the cast iron bridges, lamps, flagpoles and planters used throughout Central Park.

The stonework with the piers and planters showed how Vaux and Wisedell implemented a planning and decorative theme which united music and nature into an outdoor theatrical experience. To augment that experience, Vaux and Wisedell also added a restaurant and pavilion which will be discussed in the next article.

Further Reading:

- Annual Reports of the Brooklyn Park Commissioners. 1861-1873 (Brooklyn, N.Y., 1873).

- Olmsted, F.L and Vaux, Calvert, Description of a Plan for Central Park. “Greensward.” (New York: The Aldine Press, 1858, reprinted 1868).

- Flores, Carol A. Hrvol, Owen Jones: Design, Ornament, Architecture, and Theory in an Age in Transition (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 2006)

- Kowsky, Francis R., Country, Park & City: The Architecture and Life of Calvert Vaux (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).

- The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted. Volume IV: The Years of Olmsted, Vaux & Company (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992).

- Roper, Laura Wood, F.L.O.: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973).

- Rybczynski, Witold, A Clearing in the Distance. Frederick Law Olmsted and America in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Scribner, 1999).