In 1876, Thomas Wisedell and Calvert Vaux collaborated in writing a major section of a large publication entitled A Domestic Cyclopaedia of Practical Information later re-titled Goodholme’s Domestic Cyclopaedia of Practical Information. This was a massive undertaking by the publishing house of Henry Holt & Company of New York. Its editor was supposedly a man named Todd S. Goodholme, though that was a probably a fabricated and fictitious name and some historians have suggested that Calvert Vaux was its editor. The reality appears that the cyclopaedia had numerous well-known authors who re-wrote sections of their own books which were then compiled by the publisher.

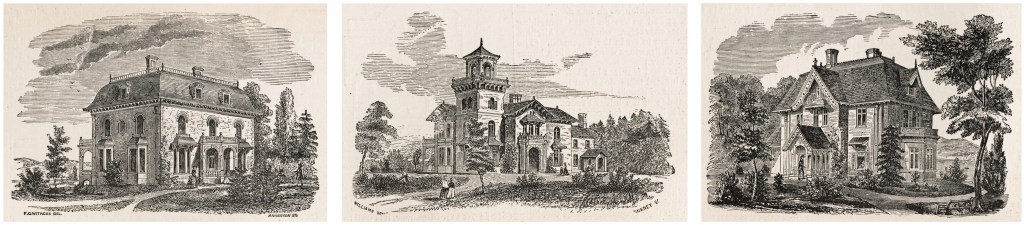

What probably led to the speculation that Calvert Vaux was its editor was that the section entitled “The House” was the largest single entry in the cyclopaedia with about forty-five illustrations being reprinted from his well-known and highly successful Villas and Cottages which was originally published in 1857 and had gone through numerous re-printings and editions, most recently re-released in 1874. (That book is still in print and ranks as one of the highest selling pattern books for houses in American history.) Vaux would have been well aware of the fact that most of the designs and illustrations from Villas and Cottages represented the early-mid 1850’s and were stylishly outdated, though much of its practical information was still quite relevant.

In terms of taste, American domestic architecture was quickly moving towards the Aesthetic Movement and Queen Anne styles emanating from England. Advances in wood frame construction and brick-laying techniques as well and new methods for plumbing, heating and ventilation were pushing design in a more cosmopolitan direction. With the publication of numerous home decorating books and periodical as well as the influences felt after the Centennial Exposition of 1876 in Philadelphia, the American public was now demanding changes in how their homes would be planned, constructed and decorated.

Enter Thomas Wisedell. Vaux and Wisedell re-wrote most of the text from Villas and Cottages to represent technological, cultural and stylistic changes. When Vaux was designing in the 1840 and 1850’s, men were making most of the decisions for the construction of the homes. By the mid-1870’s, that role was now dominated by women and the language of the pattern books reflected that cultural shift. What was perhaps the single most influential home decorating book from this period was Hints on Household Taste by Charles Locke Eastlake published in London in 1868. The book was immediately popular in the United States, especially in Philadelphia, New York, Hartford and Boston where its influences were felt long before the first American edition was published in 1872. As for Goodholme’s Domestic Cyclopaedia, the entire section regarding furniture, carpets and wallpapers was written by the architect and designer George Fletcher Babb and relied almost solely on British examples. (Though it is not known who designed the covers for the cyclopaedia’s various editions, Babb would probably be the most likely candidate.)

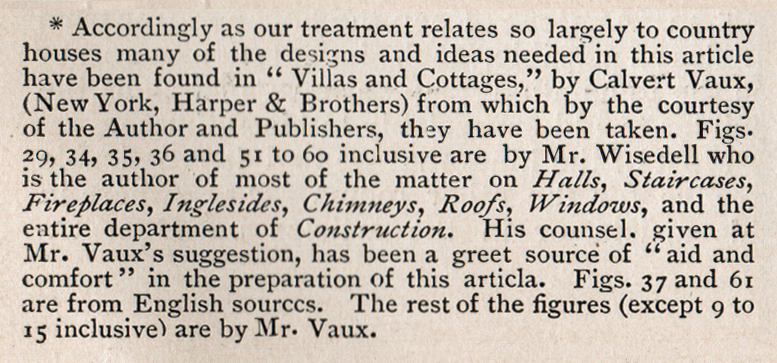

As mentioned in previous posts, Calvert Vaux was very generous and precise when it came to recognizing and crediting the people who worked alongside him on various projects, and this was no exception. As the above illustration shows, Thomas Wisedell’s contributions were rather extensive. Since most of his experience under R.J. Withers and Olmsted & Vaux was principally in decorative designs, Wisedell had limited experience with designing entire houses or buildings (later posts, however, will address some of those projects). Perhaps due to this limitation, it would principally be Vaux’ illustrations from Villas and Cottages that accompanied Wisedell’s writings on fireplaces, inglesides, chimneys and roofs.

Bottom: Hall and Staircase Hall (nos. 2 and 5 on the plan).

Calvert Vaux never fully adopted the Queen Anne style and though both he and Thomas Wisedell were quite familiar with contemporary British publications, it was an idiom which neither had fully explored. This may explain why when Wisedell wrote his section regarding the stairhall, he had illustrated it with examples from a house designed by Josiah Cleveland Cady, a fellow New York architect. Rather than using Cady’s renderings, however, the elevation, plan and interior were all drawn by Thomas Wisedell.

To include another type of stairhall, an illustration by the British architect John M. Broydon which had originally appeared in the London publication, Building News in 1873 was also included. This was probably the publisher’s decision rather than either Vaux’ or Wisedell’s. The reason that I say this is that another New York architect, H. Hudson Holly was writing his book Modern Dwellings at the same time though it would not be published until the following year in 1878. That book also included the same image and it would become well known as the the first American pattern book to almost fully rely on the writings of C. L. Eastlake and include British design history and references, especially to Richard Norman Shaw. Though Holly was from New York, he was trained in the office of Gervase Wheeler, a British architect who had immigrated to the United states around 1846. (One of Wheeler’s earliest designs was in East Hartford for the father of Frederick Law Olmsted.) Because of this training, Holly maintained British designed influences throughout his entire career.

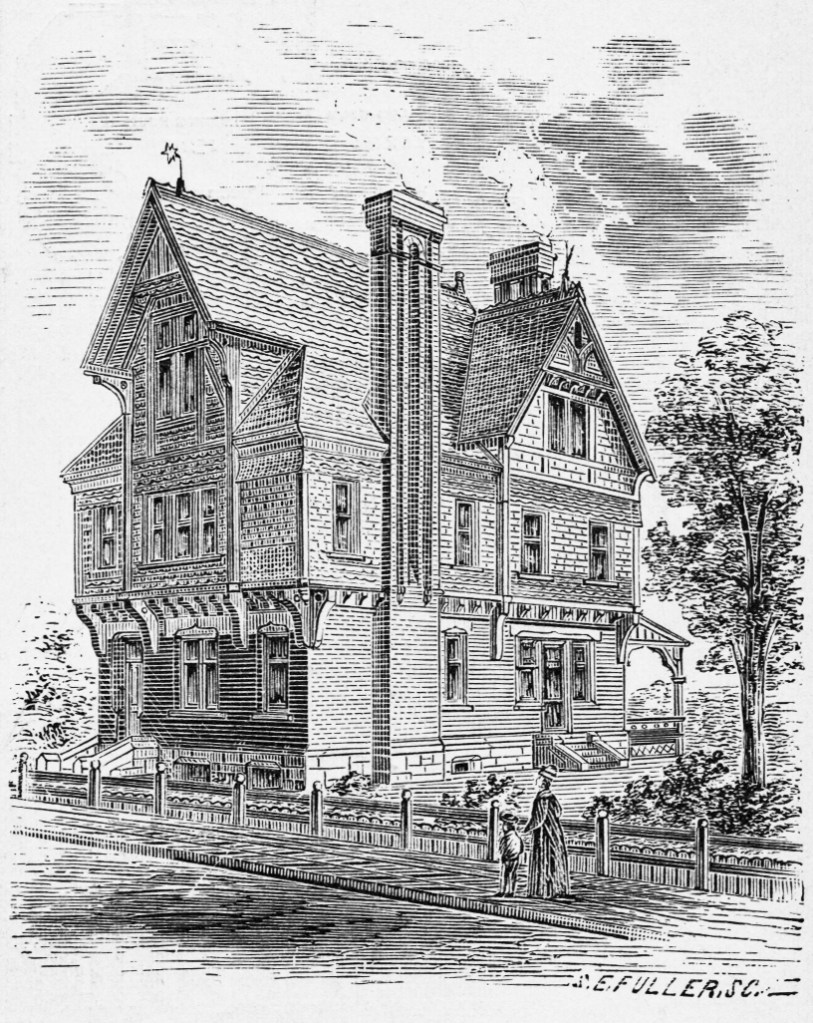

Though many illustrations in the cyclopaedia had come from previous sources, Figure 29 was created by Thomas Wisedell to illustrate how the the standard square plans of those earlier houses could be enhanced through picturesque effects. Though this has was never constructed, it does exist as the earliest known original house design created by Wisedell and shows that he was fully aware of developments happening in England.

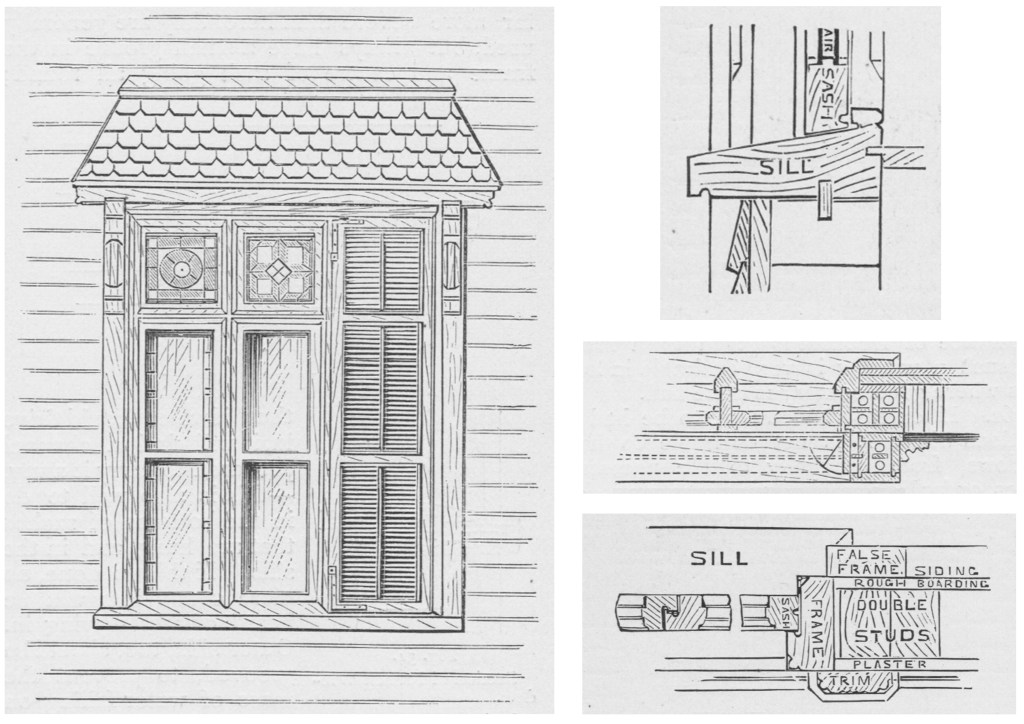

What was perhaps Wisedell’s most important contribution to The Domestic Cyclopaedia was his writings and drawings regarding construction. This was first displayed on the section he wrote regarding windows. Not only did he illustrated various ideas for plain and shuttered windows, but also showed the effects of incorporating stained side lights. Besides those aesthetic features, he also included detailed construction drawings.

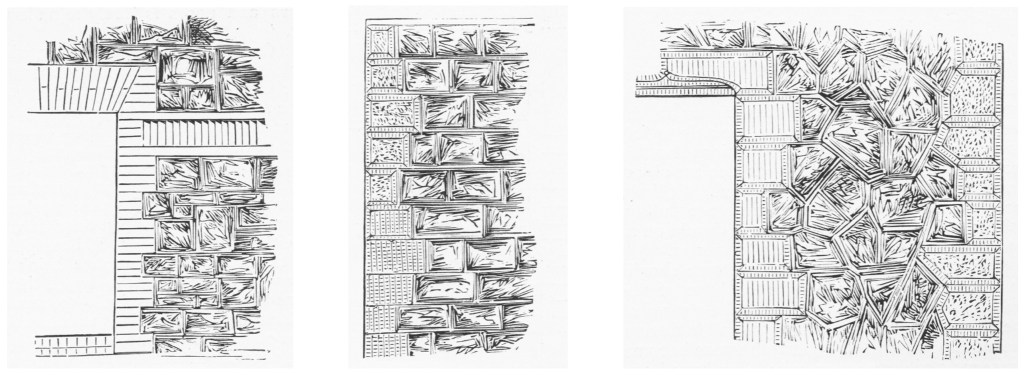

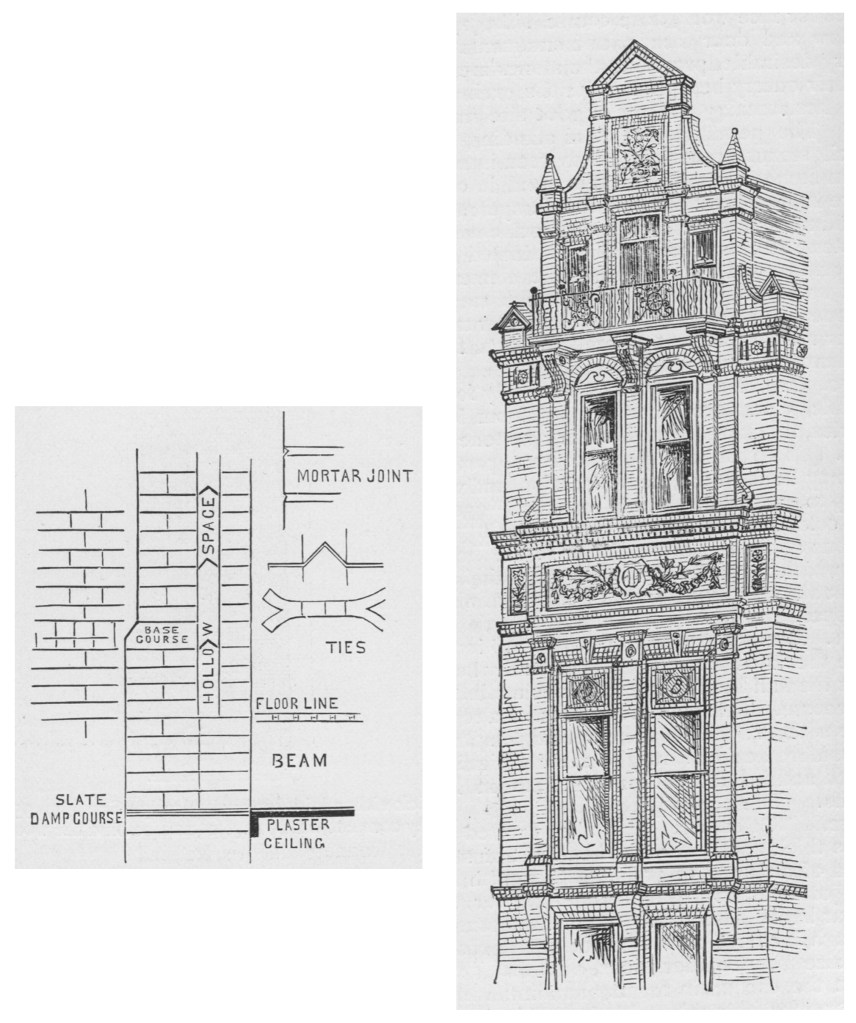

Following his writing on windows, Wisedell added a two-part section entitled “Construction.” The first part was on stone and brick houses and gave practical advise on all stages of construction from proper drainage and foundations to ways of cutting stone and laying brick as well as building interior walls. What was the common theme throughout was how to incorporate hollow spaces in the interior and exterior walls in order to avoid water problems which would lead to mold and mildew.

Center: Rough-cut coursed ashlar.

Right: Irregular ashlar with coursed quoins.

Right: Example of ornamental brick work, H. C. Von Post residence, New York City.

Besides proper construction methods, Wisedell also included a section on “Ornamental Brick Work” highlighting the fact that this was already a common practice in England. To Illustrate how this trend in England could be applied buildings in the United States, he included an elevation drawing from a house designed in 1876 by William Wheeler Smith for Herman C. Von Post, located at 32 W. 57th St in New York City. This was one of the first examples of this the Queen Anne style applied to an urban row house anywhere in the United States and would proliferate into the 1890’s. Wisedell himself would become quite adept at the style with his designs from the late 1870’s and early 1880’s during his partnership with Francis Kimball.

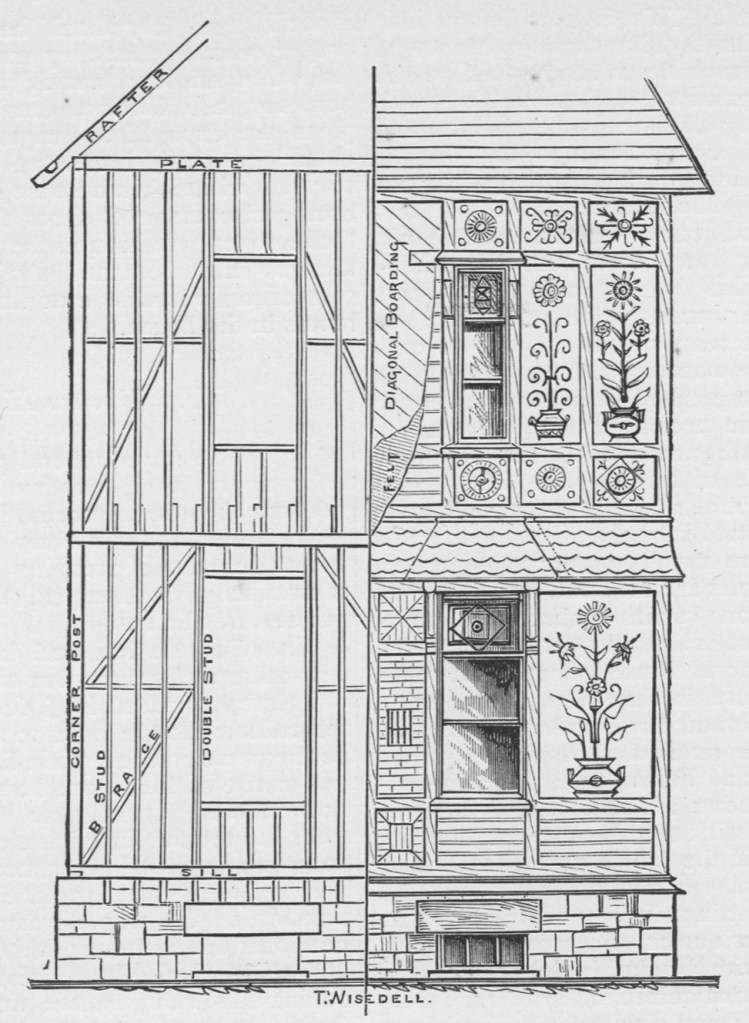

Part two of Wisedell’s writing on Construction focused on wood frame houses. Instead of hollow walls, Wisedell’s focus was on proper techniques for creating a structural frame. Most of the section was devoted to cladding and infilling. Besides clapboard and shingles, he also included ways of adding decorative elements through plaster and sgraffito, casting designs in cement or plaster, and using non-structural, decorative brick patterns as infill. He does note however, that most of those techniques were common in England but rarely attempted in the United States.

Though this was only an introduction to Wisedell’s contribution to this publication, the entire book served as a comprehensive glimpse into Victorian tastes and technology and would have been quite valuable in any household. Since it was a volume too extensive to fully cover in one posting, I’ve included a link for anyone to access the entire publication.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015093192410&seq=5

Further Reading:

- Eastlake, Charles Locke, Hints on Household Taste in Furniture, Upholstery and Other Details (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1868, revised in 1869).

- Goodholme, Todd S., editor, A Domestic Cyclopaedia of Practical Information (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1877).

- Goodholme, Todd S., editor, A Domestic Cyclopaedia of Practical Information (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1882).

- Goodholme, Todd S., editor, A Domestic Cyclopaedia of Practical Information (New York: C.A. Montgomery & Co., 1885).

- Goodholme, Todd S., editor, A Domestic Cyclopaedia of Practical Information (New York: C.A. Montgomery & Co., 1887).

- Goodholme, Todd S., editor, Goodholme’s Domestic Cyclopaedia of Practical Information, new and revised edition (New York: Charles Scribner & Sons, 1889).

- Holly, H. Hudson, Modern Dwellings in Town and Country Adapted to American Wants and Climate with a Treatise on Furniture and Decoration (New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1878).

- Vaux, Calvert, Villas and Cottages. A Series of designs Prepared for Execution in the United States (New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1857).